By David Gutman

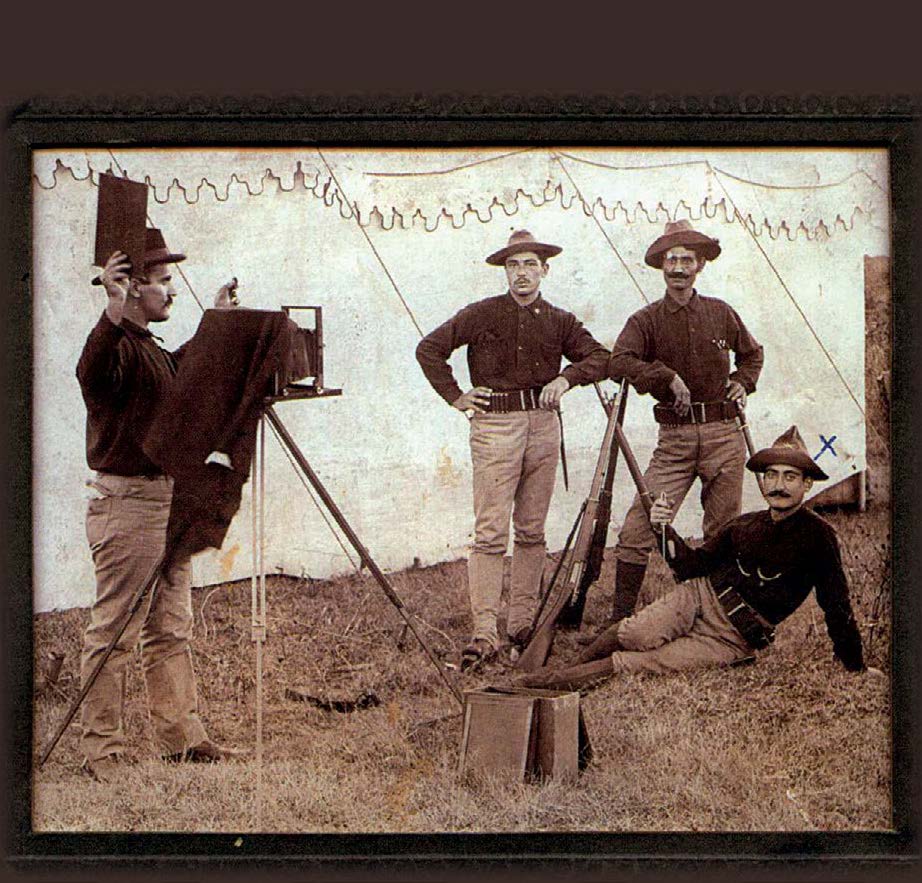

In April 1906, a man appeared at the United States consulate in Sivas, a city located deep in the Anatolian interior in what is today central Turkey. In fluent English, the man identified himself as Ohannes Topalian, a resident of Kayseri, a city located 120 miles to the southwest. Ohannes told the consul how fifteen years earlier, he had setoff for the United States in search of work and perhaps a small fortune. Overcoming a ban imposed by the Ottoman state on Armenian migration to North America that had been in place since the late 1880s, he found his way to Providence, Rhode Island. In March 1898, Ohannes naturalized as a United States citizen. Filled with a sense of patriotic duty to his adopted country, he enlisted in the army and shipped out to Cuba soon thereafter. After serving valiantly in the Spanish American War, Ohannes was honorably discharged the following year.

But there was a void in his life. He wanted to start a family, and his aging father had arranged a bride for him back home. So in 1901, he set sail again, returning to the land of his birth. But his return trip was hardly a straightforward one. He had migrated unlawfully to the United States, and, what’s more, he had naturalized as a citizen of a foreign state in contravention of imperial law. Because of this, he knew that if he simply showed up at an Ottoman port, he was likely to be barred from reentry. So he spent six months living and working in Egypt, an Ottoman province under de facto British rule, where he acquired a travel pass that allowed him to make the trek back home without incident. Over the next few years, he married and had a child.

It had always been Ohannes’ intention to return to his adopted country. This meant once again having to make the illicit voyage, now with his wife and young daughter in tow. Certainly, he thought to himself, the trip would be made easier if he possessed an American passport. And this is how he ended up before the U.S. consul in Sivas on that chilly day in early April. He had with him several documents attesting to his status as an American citizen: his naturalization records and his military discharge papers foremost among them. To allay any doubt the consul might have, he even performed drill exercises. Ohannes was confident that he would be granted a passport. And thus the consul’s words refusing assistance landed like a punch to the gut. Since his return to the empire, he had been living, working, and paying taxes like any other Ottoman subject. After all, if he made it known to local authorities that he had unlawfully become a U.S. citizen, he faced imprisonment or even deportation. He had no other choice but to conceal his status. Now the consul was informing him that according to American government policy, by doing so he had forfeited any right to protection as a citizen. Ohannes would make the long trip back to Kayseri empty handed. Undeterred, a few months later he travelled to Egypt where he visited the consulate in Alexandria hoping for better success there. Once again, his request for a passport was denied.

Ohannes Topalian’s story is a particularly keen demonstration of the difficulties that faced Armenian migrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For the Ottoman state, Armenians who travelled to North America and then returned to their home communities posed an intolerable risk to the empire’s internal security. In the minds of imperial bureaucrats, migration invariably led to political radicalization, and all migrants were presumed to be dangerous subversives. At the same time, the United States was in the midst of an era marked by increasingly virulent and racist anti-immigrant politics, and the introduction of restrictionist legislation that continues to serve as the basis of present-day immigration law. In the first years of the 20th century, just as Ohannes was making his way back to the Ottoman Empire and starting his family, the Ottoman and United States governments came to an agreement that American diplomatic personnel would not recognize the status of Armenians who returned to the empire after having naturalized as U.S. citizens. Thereafter Armenians like Ohannes found themselves the targets of the anti-migrant policies of not one but two states.

Luckily for Ohannes and his family, they eventually made it to the United States. In 1915, most Ottoman Armenians would be killed or forcefully deported to the Syrian Desert. Ohannes lived until ripe old age in his adopted homeland. But over the past century, more and more migrants like him have been forced to overcome increasingly daunting restrictions on their ability to cross borders. Much like Ohannes, those who succeed often find themselves living in an uncomfortable and often dangerous legal limbo. His story features prominently in my book, The Politics of Armenian Migration to North America, 1885-1915: Sojourners, Smugglers and Dubious Citizens in which I argue that the Armenian migrant experience in the late 19th and early 20th centuries has much to tell us about the dynamics that continue to drive migration and mobility control in the present day.

David Gutman is Associate Professor of History at Manhattanville College. The Politics of Armenian Migration to North America, 1885-1915 – published in the Edinburgh Studies on the Ottoman Empire series – is his first book. He is also the author of several articles and book reviews on the topics of migration, mobility control and genocide.