by Joseph Petek

If Alfred North Whitehead had taken care to preserve the drafts of his books and essays, his lecture notes, and his correspondence – in short, left behind the sort of Nachlass that important scholars often do – then a critical edition of his writings would no doubt have taken place long before now. As it stands, the idea of a Critical Edition of Whitehead was ignored for many years.

This was partly because it seemed that there was nothing substantive left to pick over. Stories began to circulate shortly after Whitehead’s death that he had asked for his papers to be burned. This seemed to be confirmed in the first volume of Victor Lowe’s biography Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and His Work (1985). We now know that this story is not completely true. Nonetheless, we have never found an original manuscript for any of Whitehead’s books; only a few articles with emendations.

Finding another way to reconstruct Whitehead’s drafts

What few people suspected until recently is that the missing drafts for Whitehead’s books might still exist – in the notes of his Harvard and Radcliffe lectures. In retrospect, such a possibility should have been obvious. For one, Whitehead comes right out and says in the preface to Process and Reality:

In the expansion of these lectures to dimensions of the present book, I have been greatly indebted to the critical difficulties suggested by the members of my Harvard classes.

There does not appear to be much room for interpretation here. Whitehead says that he tested out his philosophical ideas in his Harvard classroom. And he integrated the feedback he received into his published writings.

‘Thought in action’

Then there are the descriptions of his lecturing style, which suggest spontaneity and ‘thought in action’:

In the lecture room [Whitehead] gave the appearance of complete spontaneity. He did not deliver a set piece; his lecture was thought in action. Those who know him only from his books have missed something of his mind; for he was happier, easier, freer in speech than in writing. The listener had the experience of being taken behind the scenes and witnessing the very process of creative thinking, with its doubts and queries, its problems genuinely felt, in an unfinished but living form.

Raphael Demos et al, ‘Proceedings of the American Philosophical Association 1948–1949’, The Philosophical Review 58(5)

We see more evidence of what went on in Whitehead’s classroom in the second volume of Lowe’s biography. In a letter to Mark Barr, Whitehead wrote:

I do not feel inclined to undertake the systematic training of students in the critical study of other philosophers… [but] I should greatly value the opportunity of expressing in lectures and in less formal manner the philosophical ideas which have accumulated in my mind.

Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and His Work, Volume II: 1910–1947

And lastly, examining the notes themselves, we have Louise Heath’s observation from fall 1925:

Theoretically [this was the] same course as 1924, but I credited it because actually it was quite different.

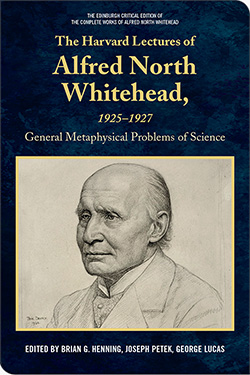

Brian G. Henning, Joseph Petek, and George R. Lucas, Jr. (eds), The Harvard Lectures of Alfred North Whitehead, 1925–1927: General Metaphysical Problems of Science

Whitehead’s Harvard lectures

This evidence suggests that Whitehead was not teaching a static curriculum that remained the same from year to year. Rather, he lectured his Harvard students on whatever philosophical ideas he was currently thinking about. He was using his classroom as a forum to develop his ideas prior to formalizing them in his books. In this sense, we can see Whitehead’s Harvard lectures as the ‘drafts’ of his books whose absence scholars have so long lamented.

I hope that readers can appreciate that I am not exaggerating when I say that the second volume of Whitehead’s Harvard lectures is an invaluable resource to scholars that will change our understanding of Whitehead’s philosophy forever. It painstakingly reconstructs his second and third year of lectures at Harvard based on the notes of his colleagues and students. In doing so, it provides a unique window into the development of Whitehead’s philosophy between the publication of Science and the Modern World and his Gifford lectures of June 1928, which would become Process and Reality. It will likely take years for all the implications of this volume to be fully teased out. But, for the moment, we can at least celebrate that there has never been a more exciting time to be studying Whitehead.

About the author

Joseph Petek is a doctoral candidate in process thought at Claremont School of Theology. He is the Chief Archivist of the Whitehead Research Project and Assistant Series Editor for The Edinburgh Critical Edition of the Complete Works of Alfred North Whitehead.

Also by Joseph Petek:

Image credits

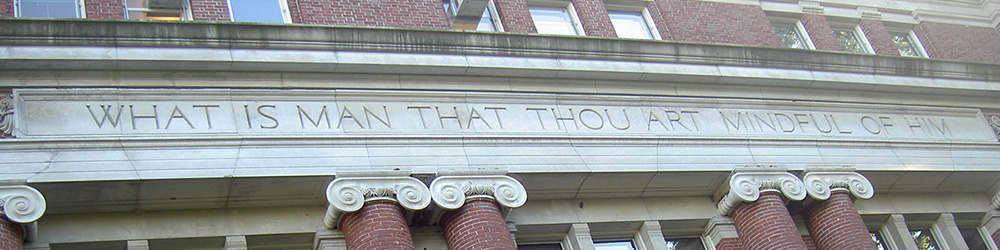

- Detail from ‘060920emerson Emerson Hall at Harvard‘ by Dan4th Nicholas via Flickr

- ‘Harvard University image of Whitehead, circa 1924‘, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Find out more

Did you enjoy ‘The missing drafts of Whitehead’s books’? Discover the lecture notes to the Whitehead’s second and third years at Harvard in The Harvard Lectures of Alfred North Whitehead, 1925-1927: General Metaphysical Problems of Science, edited by Brian G. Henning, Joseph Petek & George Lucas. Or find out more about the The Edinburgh Critical Edition of the Complete Works of Alfred North Whitehead.