By Nathan Ashman

It was 2006 and James Ellroy was in the midst of penning the much anticipated third volume in his ‘Underworld USA Trilogy’, an epic criminal history of post-war America. I, meanwhile, was just about to begin my second year of college where I was studying an eclectic and ill-judged assemblage of A-level subjects (including an A-level in ‘Leisure Studies’… I’m still not sure what this means). English Literature was another of my choices, but I wasn’t a particularly enthused or voracious reader at this point in my life. Crime fiction was certainly not on my radar. Nor for that matter, was Ellroy. What I did love though, was film.

In my down time away from the rigours of studying ‘leisure’, me and my buddy Ross would spend pretty much all our free time at the cinema. Admittedly, there wasn’t a whole lot else to do in Swindon, but our relationship with movies was still borderline obsessive. So much so that earlier that year we had both invested in a Cineworld ‘Unlimited Card’ (£9.99 a month, all the movies you could hope to see), a veritable golden ticket for movie-going nerdery. 2006 was a mixed year for movies I would say. We had the highs of Children of Men, and the lows The Butterfly Effect 2. But it didn’t matter! We would watch them all: the good, the bad and the ugly.

One movie released in 2006 was Brian De Palma’s much maligned adaption of James Ellroy’s neo-noir novel The Black Dahlia. I hadn’t heard of Ellroy (or the novel) but did claim to be a huge fan of De Palma (having caught the last 10 mins of The Untouchables at nan’s over Christmas). So, we went and, well, we hated it. We laughed at the hammy acting, the convoluted plot and overly contrived period aesthetic. We dissected the flaws in the script and the hollowness of De Palma’s direction, all with breath-taking levels of adolescent smugness. We decided, unanimously, that it was a terrible film.

And I forgot about it, or so I thought. The iconography of that film left an indelible mark on my psyche, on a level I still don’t really understand. Was it the flawed cops? The degenerate families? The sleazy corrupt underbelly of Los Angeles? I’m not sure, but years later I would find myself drawn to the cover of Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia whilst aimlessly browsing a Waterstones bookshop. This was 2012. I had just finished my MA at the University of Portsmouth and was considering doing a PhD.

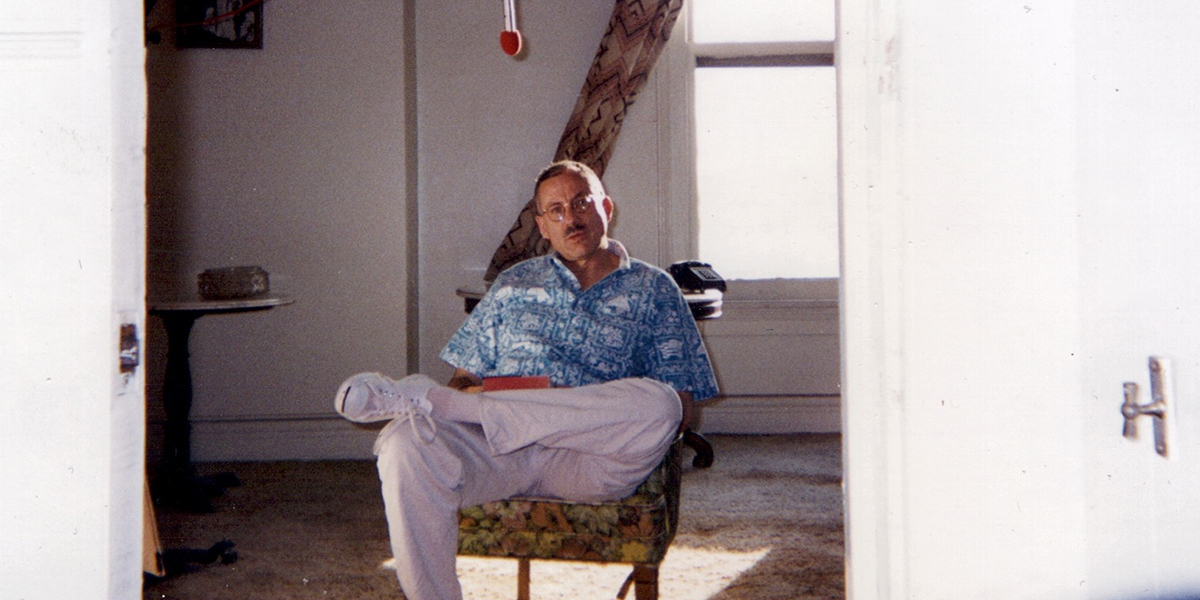

In many ways, reading The Black Dahlia is one of the single most significant moments of my life. I was blown away by it. The corruption, the sleaze, the style. Everything about it hooked me. I coveted Ellroy that summer, reading everything I could get my hands on. I also began to read about the man himself, this bombastic and divisive figure whose mother was murdered when he was only a boy. I would watch interviews with Ellroy where he would fragrantly espouse right wing sentiments, all the while casually dropping in anachronistic and regressive racial epithets. Could this man, this controversial contrarian really be the same James Ellroy who wrote these novels I loved so much? I applied for a PhD at the University of Surrey and there was only one subject I was interested in studying –James Ellroy.

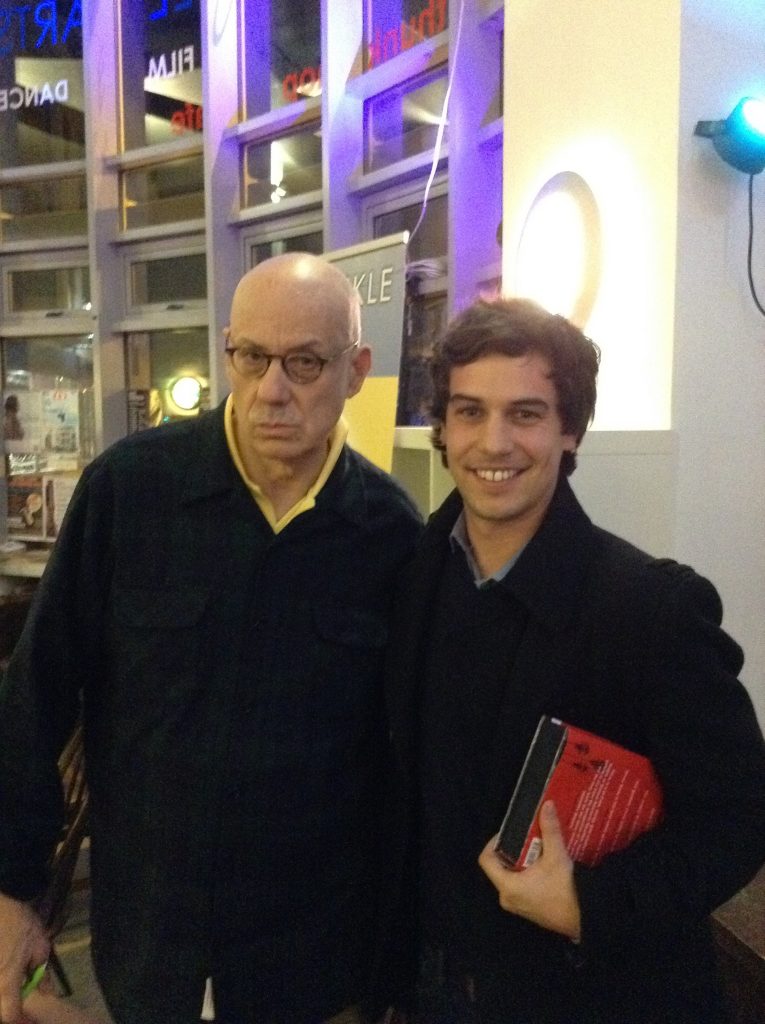

My own relationship with Ellroy has always been mired in contradiction. I often feel an irrational impulse to critically defend his works against accusation of xenophobia, misogyny and racism, whilst at the same time feeling that there is a certain validity to these claims. I have met Ellroy a couple of times at promotional events and he’s always been polite, engaging and incredibly generous with his time (and on both occasions has praised my follicle gifts whilst bemoaning his own premature baldness… just the kind of in-depth conversation I was hoping for). But the ambivalence persists.

My contribution to Crime Fiction Studies is symptomatic of my ongoing efforts to grapple with the tensions and contradictions in Ellroy’s life and works. Ostensibly the essay is an examination of the male bonds in Ellroy’s most recent novel, This Storm. Utilising Eve Sedgwick’s work on ‘homosocial bonding’, it looks to expose the fragility and paranoia of masculine identity in Ellroy’s fiction. Ultimately it argues that while Ellroy’s novels may appear to celebrate a regressive mode of ruthless, heterosexual masculinity, they simultaneously expose it as a paranoid construct, one that is always grappling with its own perilous self-definition. I hope you enjoy it!

I should note also that I now actually have a real soft spot for De Palma’s The Black Dahlia. It’s flawed… but its okay to like things that are flawed, right?

By Nathan Ashman

Nathan’s article will appear in a forthcoming issue of Crime Fiction Studies, the journal of the International Crime Fiction Association. Find out how to subscribe, and recommend to your library.