Towards the end of Sally Rooney’s acclaimed novel Normal People, the two main characters, Connell and Marianne, talk sleepily one morning about whether it’s possible ever really to know another person. ‘I guess everyone is a mystery in a way’, Marianne says. ‘I mean, you can never really know another person, and so on’. Connell is sceptical: ‘Yeah. Do you really think that, though?’ ‘People are a lot more knowable than they think they are’, he says. Both characters feel, by this stage of the story, that they know each other intimately. After Marianne has showered, however, Connell will tell her something about himself that he had previously hidden from her, and that has the potential to change their relationship profoundly.

There’s a lot going in in this conversation. Connell rejects the apparently hackneyed idea that other people are impossible to know, but it’s an idea he is likely to have come across (as I did) in his Critical Theory classes, as a student of English at Trinity College Dublin. The unknowableness of the self is an idea that has its roots in Freudian psychoanalysis: our unconscious effectively makes each of us a stranger to ourselves, as the literary theorist Julia Kristeva puts it. Both Marianne and Connell encounter, in the course of Normal People, their inner ‘weirdness’: dark and violent impulses that make them want what they don’t want, that mean they behave in ways they don’t fully understand, and that lead them occasionally to feel suddenly strange, unlike themselves. Both main characters feel the uncomfortable urge to exert power over the other. Marianne, a victim of domestic abuse, both physical and psychological, encourages sadistic behaviour in her partners.

In 2013, a highly publicised set of experiments by the psychologists David Kidd and Emanuele Castano suggested that reading fiction can develop a person’s ‘Theory of Mind’, or the social skill of being able to infer the thoughts, feelings, and motivations of other people. A lot has rightly been made of this discovery that reading novels might actively nurture important interpersonal skills. However, my book Empathy and the Strangeness of Fiction: Readings in French Realism (Edinburgh University Press, 2020)argues that good narrative fiction also often gives us an ethical lesson as well as a social one: it tells us that people are opaque to us. They are often not thinking or feeling what we think they are thinking or feeling.

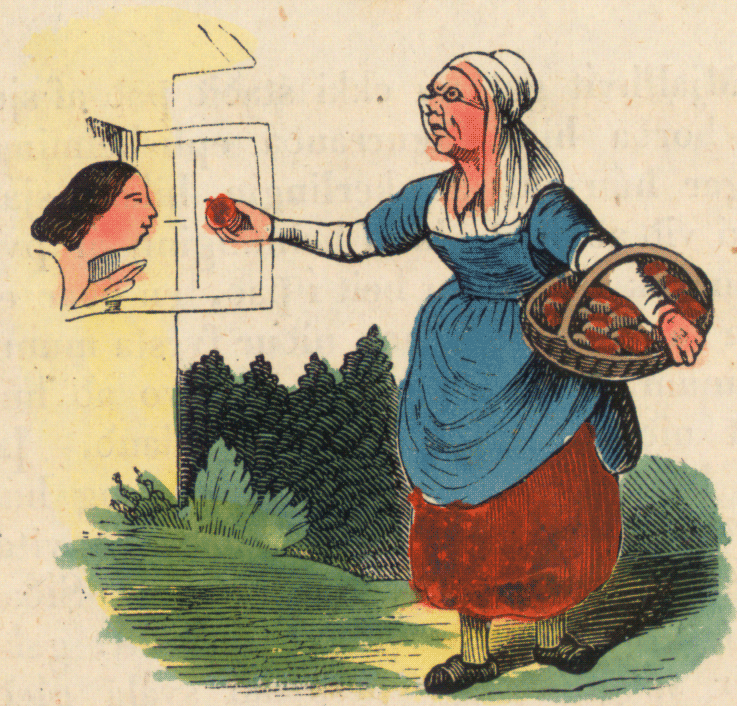

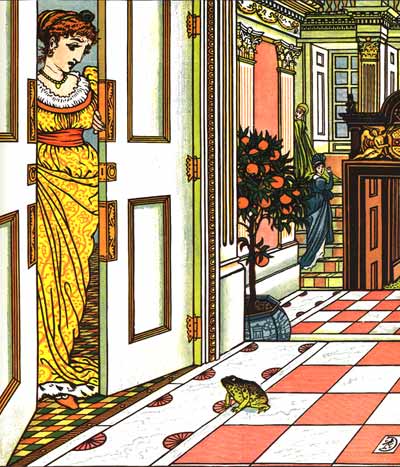

Of course we don’t need fiction to tell us that people have inner lives that are often hidden from us; anybody who has ever had an even vaguely interesting conversation with another human being can work this out. However, fiction can, like social interaction at its best, reveal that others can be different than we think they are. In fairy tales, for example, frogs and beasts can be very different than they seem, as can nice old ladies who offer a rosy apple to eat or a gingerbread house to stay in. And in terms of TV drama, one of the reasons we remain fascinated by Don Draper, Walter White, Tony Soprano, Villanelle and Eve is partly because they have dark secrets, but it’s also partly because we can never quite figure their characters out.

Our fascination with the characters of Marianne and Connell, and the relationship between them, is certainly a big part of the appeal of both the novel and the television adaptation of Normal People. The camera lingers on the faces of Daisy Edgar-Jones and Paul Mescal, capturing tiny shifts in their expressions, flickers of their eyes, like so many visual clues to what is going on inside their characters. Fiction reminds us that people can surprise us, and this is a lesson worth remembering in a world where our dealings with others are often functional and perfunctory, and where social media can give us the impression that we know everything about everyone. We don’t.

Normal People, like all good fiction maybe, reminds us that people are not as easily knowable as we might think they are, or as they themselves might think they are. If characters are opaque to each other in fiction, this is because people are opaque to each other in life. And if we people in real life are unknowable to each other, this is because we are so often unknown to ourselves. In the end, the most normal thing about us people is our strangeness.

Author profile

Dr Maria Scott is a Senior Lecturer in French at the University of Exeter. The author of Empathy and the Strangeness of Fiction: Readings in French Realism (Edinburgh University Press, 2020), and has also published books on Baudelaire and Stendhal. You can find out more about Maria through her own blog or through her university website.