By Julian Wolfreys

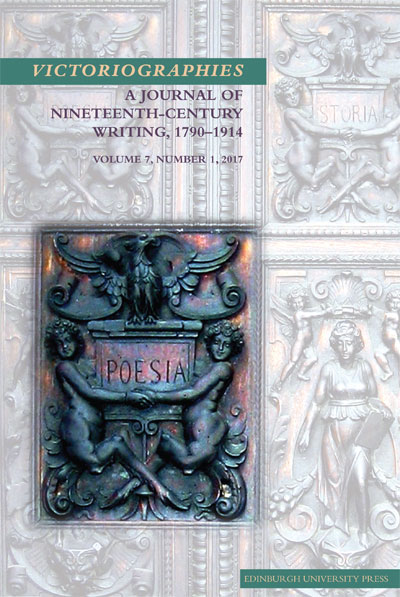

This ‘valedictory’ editorial (on the significance of Victorian) appears on the EUP Blog in two parts and is published in Victoriographies Volume 7.

People soak up time like sponges. They steep themselves in it, amass it like those who stockpile a thing they fear will run out.

– Andrzej Stasiuk

Listen. You know what it’s like when you’re in a room with the light on and then suddenly the light goes out? I’ll show you. It’s like this.

– Harold Pinter

Victoriographies: the term came to me somewhere in 1995, I think, as a neologism doing double service: on the one hand, it captured the idea of all Victorian writing, all writing of the so-called Victorian period, era, epoch, what have you – though if the final, then the question has to be asked, are we not still in this epoch, in the grip of a moment of radical suspension where what was modern for the Victorians has now become Victorian for us, those who are Victorian by virtue of the fact that, far from being post-modern, we’re not even modern enough, not yet modern? On the other hand, there was a sense that to write on, of, about ‘Victorian’, this was too to produce a ‘Victorian writing’, a Victoriography. The plural signalled by the grammatical ending sought to suggest this ‘on the one hand…on the other’ situation, and to gesture economically also toward the sense I had, and still do, that there was more than one ‘Victorian’ culture, many more ways of identifying a ‘period’, so-called than by the dominant, hegemonic traits, traces, monuments, and canonical works. Then also, the idea was that the term should serve, in being about writing, also to address writing that, coming before the moment of Victoria was nonetheless ‘Victorian’ as it were, avant la lettre, that it laid the ground, did the thinking, set the stage, was in fact and in all or many material conditions Victorian in all but name. Hence the provisional inaugural date appended to the title. At the other end, there is a concluding date – nothing more than a convenient fiction, as recent events and phenomena have shown. 1914 was suggested to me by a then-colleague; in retrospect, I think I would have signalled a later moment, the year of the publication of, say, The Waste Land, Mrs Dalloway, Ulysses. Recalling this reveals to me a difference in thinking between me and my colleague, which is, in truth a much broader thinking. Though a literary scholar, he was thinking primarily historically, while I was thinking in terms of the literary text. This may be a small matter, it may not. It is not for me to judge, much less reflect on the way in which Victorian studies has developed or moved.

Anyone wishing to do so could do far worse than to look at the articles published in Victoriographies over the past six years. (The journal is now entering its seventh year; in the past year, it has moved from two to three issues a year, its growth steady, and that growth a sign, surely, of its success in speaking to and reflecting its audience). Taking a look at the first issue again, I see it was a special issue, the theme being ‘Wither Victorian Studies’ with articles critiquing New Historicism (John Kucich), a look at possible futures (Regenia Gagnier), legacies of the Victorian age (Catherine Robson), and Ruth Robbins’ examination of Victorian themes and forms in the Edwardian novel: the first issue now seems to me to be a veritable angel of history, moving forward, looking back, but also looking to whatever is to come while also gathering the past as it moves. This first issue also had a general section with two essays on the relationship between Kant and Wilde, and Wilde and Pater. The first issue set a model for structure, and demonstrated a breadth, a cultural and historical scope of interest and inquiry. The most recent volume, another special issue, ‘Longevity Networks’ is equally diverse, ranging from Shelley to Machen, and addressing how literary and cultural phenomena endure, persist. All things Victorian converge and are in good shape; there is still life in the revenants of the nineteenth century; to paraphrase that most modern of Victorian characters (someone whose view on Brexit would have been most interesting), the fascinations, obsessions, and interests of the nineteenth century are in full vigour; nothing has occurred to stop them in their useful course. So far, so Victorian, or plus ça change; the more things change the more they stay the same. Why, as I write, you can turn on your TV set and enjoy the prospect of Tom Hardy (ha!) dressed in black fustian, with a tall hat, bespattered from foot to neck in mud, chewing his way through his half-grown beard, a poorly lit London of 1814, and a plot of such Gothic proportions that it would have put Sheridan Le Fanu and Wilkie Collins to shame, ably abetted by Edward Fox, impressive as a corpse, and Jonathan Pryce, anachronistically ‘fucking’ and ‘bastard-ing’ all over the East India Company. Dickens would be proud, Wilde would be witty in disbelief, and George Eliot would have something pithy to say about boys’ own adventures, ripping yarns, and all stories beginning in medias res.

Taking a look at the first issue again, I see it was a special issue, the theme being ‘Wither Victorian Studies’ with articles critiquing New Historicism (John Kucich), a look at possible futures (Regenia Gagnier), legacies of the Victorian age (Catherine Robson), and Ruth Robbins’ examination of Victorian themes and forms in the Edwardian novel: the first issue now seems to me to be a veritable angel of history, moving forward, looking back, but also looking to whatever is to come while also gathering the past as it moves. This first issue also had a general section with two essays on the relationship between Kant and Wilde, and Wilde and Pater. The first issue set a model for structure, and demonstrated a breadth, a cultural and historical scope of interest and inquiry. The most recent volume, another special issue, ‘Longevity Networks’ is equally diverse, ranging from Shelley to Machen, and addressing how literary and cultural phenomena endure, persist. All things Victorian converge and are in good shape; there is still life in the revenants of the nineteenth century; to paraphrase that most modern of Victorian characters (someone whose view on Brexit would have been most interesting), the fascinations, obsessions, and interests of the nineteenth century are in full vigour; nothing has occurred to stop them in their useful course. So far, so Victorian, or plus ça change; the more things change the more they stay the same. Why, as I write, you can turn on your TV set and enjoy the prospect of Tom Hardy (ha!) dressed in black fustian, with a tall hat, bespattered from foot to neck in mud, chewing his way through his half-grown beard, a poorly lit London of 1814, and a plot of such Gothic proportions that it would have put Sheridan Le Fanu and Wilkie Collins to shame, ably abetted by Edward Fox, impressive as a corpse, and Jonathan Pryce, anachronistically ‘fucking’ and ‘bastard-ing’ all over the East India Company. Dickens would be proud, Wilde would be witty in disbelief, and George Eliot would have something pithy to say about boys’ own adventures, ripping yarns, and all stories beginning in medias res.

Another colleague, a German, asked me one morning around about the time that the journal was first published, while we were walking through a very snowy and cold Berlin, why the English (he did not make the mistake so many Europeans make, thankfully, of assuming, as do the English in that very Victorian, very colonial, not to say imperial way, that England = Britain) were so very obsessed with the Victorians, why we let ourselves be so governed, haunted by our great and great-great grandparents. I replied, not a little glibly perhaps, that this perhaps was all we had, by which we could define ourselves – there was nothing else; Francis Fukuyama in The End of History and the Last Man was wrong at least to the extent that he saw this end as being a ‘result’ of neoliberal capitalism’s ‘win’ over that the monolithic authoritarian tyrannies mistakenly called communism. (A win, which in retrospect, looks more and more like a goalless draw.) History ended in England, for England perhaps, when Victoria died. Everything else has been footnoting, fiddling with the heritage, Revisionism UK PLC. Stephen Dedalus famously remarked in 1904, just three years after Victoria’s death, that history was a nightmare from which he was trying to wake. That nightmare, obviously enough, is the subject of all Joyce’s writings, the very reason his novels and short stories are set in 1904, everything, day and night, awake and asleep, taking place in a world still belonging to the Victorian Empire and not knowing how to move forward. And when you don’t move forward, as Dedalus and Bloom show us, all you can do is wander in circles, stopping for a drink every so often, until you arrive back at where you believe you started and only now realising that you’ve lost the key. Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Nigel Farrage: none are yet awake, nor do they wish to wake up; theirs is a dream of a past that never existed and which seems set to go on forever, a market culture comprising Cornish pasties and bagless vacuum cleaners. Let’s hope not.

*Notes

This brief essay is dedicated, in all respect, and full friendship, to J. Hillis Miller.