-

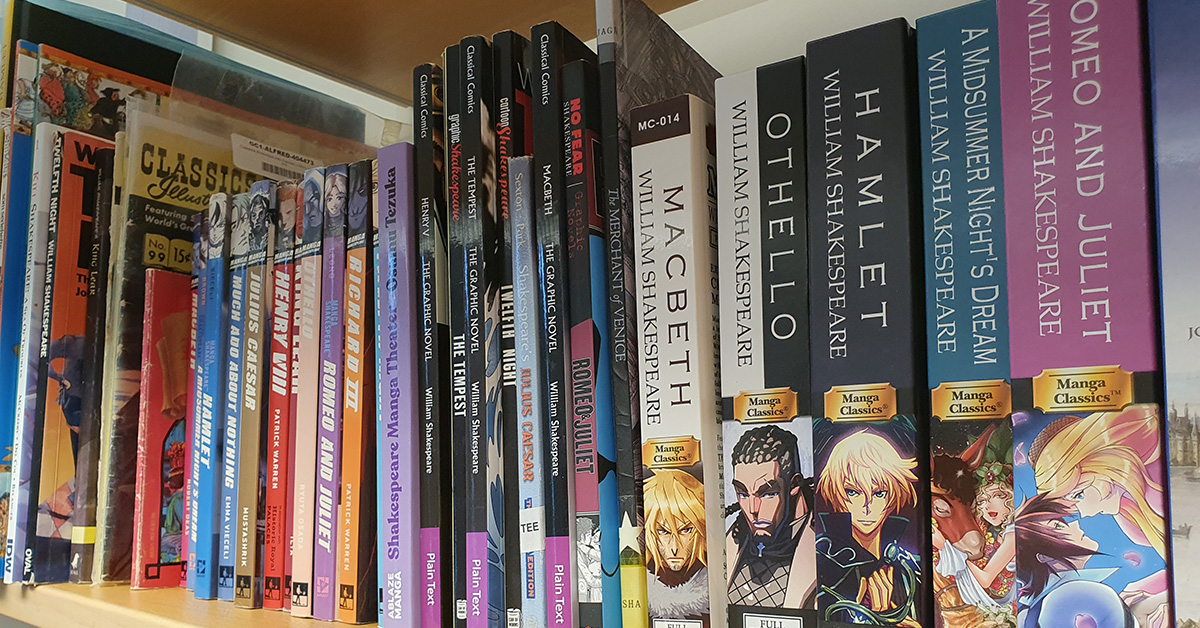

Shakespeare Comics: Q&A with the author

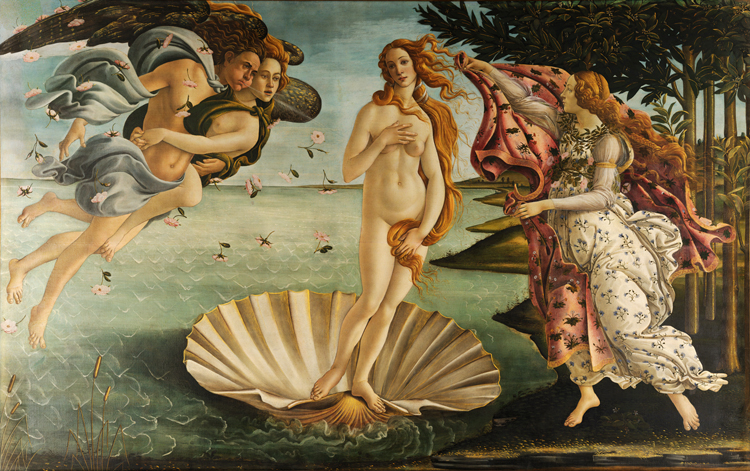

Read more: Shakespeare Comics: Q&A with the authorA Q&A on the making of Shakespeare Comics - exploring how graphic novels and manga adapt Shakespeare's plays and what they reveal about art, time, and culture.