2025 marks the centenary of the birth of Gilles Deleuze. Throughout the year, we are exploring the impact of this towering figure in twentieth-century philosophy.

As part of this celebration, we’re publishing a series of blogs from leading Deleuze scholars. This month, Kuniichi Uno explores Deleuze’s views on thinking, desire and recurring motifs in his works.

Find out more about our centenary celebrations.

By Kuniichi Uno

Why do we read Deleuze? A strange question. For does it ask: for what reason? Or for what purpose? Deleuze isn’t especially partial to reason and even less does he want to subject it to a purpose. So, the question seems at the outset inconceivable. But let us nevertheless ask ourselves, by what desire do we read and reread him?

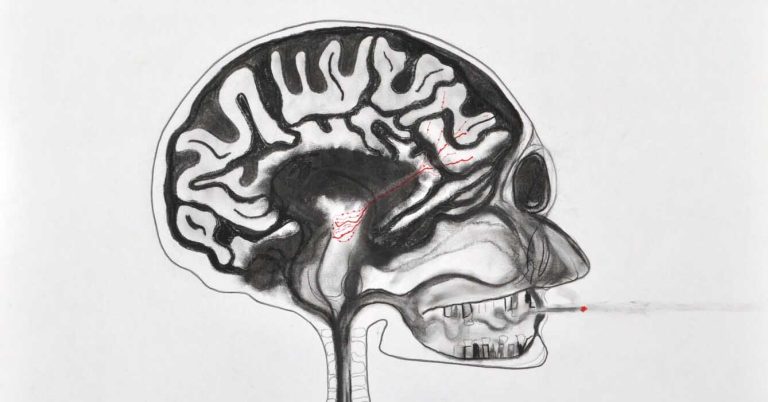

Now, desire is itself (a) complex. Every desire is an irreducibly organised ‘desiring-machine’. My own machine began revolving with two or three sentences in Difference and Repetition, wherein Deleuze wrote about what triggers thinking of someone who rarely thinks. Thinking requires a violence that compels us to think; to think (cogitare) is not, has never been a naturally given faculty. The condition of thinking is not even intelligence. Deleuze, I suspect, was the first to pose the question of what thinking is in this way. That is, a certain violence that acts on the body, brain, or the affects, that makes us desire to think.

It is not certain Deleuze has defined what this violence, these violences, are. In another sense, however, that is precisely what interests him, as a crucial, inevitable, question. All machines involve infernal exercises, productions and organisational systems that prevent one to think, stifle and freeze thought. This desire to think, whereas there are certainly dimensions in which machines equally make us desire other, different types of vitality. A small machine that triggers thinking through a molecular force; or, large machines that think for us, instead of us, that crush our thoughts: this chaos network of thinking-machines—it is Deleuze, who, together with Guattari, offered us a precise vision of this.

Stupidity, the unthought, cry, Figure, sobriety… I am listing liberally some characteristic ‘motifs’ that ring throughout Deleuze’s books. These motifs, which though at times concretising into concepts, are rather recurring themes, generate and permeate his thought, as well as trace its divergent lines.

Cry: the least philosophical word in the world. Yet if a cry fills the world, there may be no philosophy yet there, but philosophy will still be needed, not to arrest the cry, but to listen to it carefully, to make out what it conveys. Even when elucidating the sentences of a Descartes or Kant, Deleuze does so as if listening to its cry. Even an idiot thinks… The self is fractured… His course on painting is often inspired by the cries of painters, Cézanne, Klee, Francis Bacon… A cry is pre-thought, the despair before a blank (or full, it matters not which) canvas, the resistance to chaos, anger at and identification with it. Crying is a power that somehow crystallises thought.

At the same time the cry is the unthought that pulses within thought. For thinking is not self-sufficient. The unthinkable always remains. There will always be thinking that brilliantly forces the unthought into thought. But there is also thinking that follows the signs of the unthinkable, all that is obscure, confused, even inadequate to varying degrees. The unthought is like a large rock; a wall that pans across even the most intelligent brain. The unthought is not the unconscious, this latter being already elucidated, analysed, schematised and ultimately stereotyped. It is so interesting to think about the unthought. But the brain and memory are crammed with what has already been thought, with all the aspects and forms of that which has already been thought, of the objectified, of all its ‘qualities’. A question raised by Robert Musil in The Man Without Qualities.

Stupidity, along with cowardice, cruelty and baseness, ‘are not simply bodily forces, or traits of character or social phenomena, but structures of thought as such.’ No animal is ever as stupid as a human being. We, as individuals, cannot resist being stupid, because of our specific relationship to the ground (le fond) of being. Stupidity is fundamental and multi-faceted. This is not to say that we are fundamentally stupid, nor that our ground is stupidity. Stupidity arises when the ground surfaces without form, when individuation occurs without taking on a proper form, having only a distorted or distorting mirror unto itself. There are as many forms of stupidity as there are distortions. Stupidity is a mirror effect, inevitable and therefore fundamental. Philosophy especially is not immune to this interplay of ground and surface. There is no shame to desire to re-examine these forms of stupidity that can rise to the highest levels. To be human is to be ashamed, to be able to be shamelessly ‘stupid’, such that its examination carries no shame. Indeed Deleuze often exhibited a strong sense of shame in his later writings.

The concept of figure which arose as a key element in Deleuze’s thinking about painting is certainly not form, but rather ‘anti-form’. The figure is deeply related to force, to the act of painting forces without (in)forming them. The painting of the figure is neither abstract nor figurative. In his book on Francis Bacon, Deleuze begins by pointing out the power of the flat plane (l’aplat), a large monochrome area, and then moves to the figures inscribed in a contour, and he determines this composition as inspired by the art of ancient Egypt, by its treatment of planes. The figures are often flattened, crushed, thus deformed, so as to depict those forces that weigh down on the body, forces which deform, surrounded by the forces of flattening. And the role of the contour is to partition and convey the forces that are arranged in this composition of planes. This architecture of planes is a palpable resistance to Greek and classical composition in the visual arts.

The final motif, increasingly prevalent as Deleuze aged, is sobriety. Since his book with Guattari on Kafka, this word appears frequently. Regarding the writings of Kafka himself, of Beckett, of Chateaubriand; with a slightly ‘oriental’, testamentary tone, but never forgetting the will to proliferation; baroque or gothic, and through multifarious folds, it is as if he were reminding us to discard what is overly complicated, to remove the non-essential, even the essential, to retain above all the infinitesimally small, and their differences, their imperceptible relationships. A sober voice, but one that also cries. A cry in the voice of stupidity. Stupidity, in turn a gesture of the unthought, its sober gesture. Yet the strange chain of these petite motifs reveals an architecture of immense proportions.

About the author

Kuniichi Uno was born in 1948, in Tokushima Prefecture, in the south of Japan. After graduating from the Faculty of Letters at Kyoto University, he studied literature and philosophy at Paris VIII and completed his PhD dissertation on Antonin Artaud under the supervision of Deleuze. At present, he is an honorary professor at Rikkyo University. He is known for his translations of major works by Deleuze and Guattari (Anti-Oedipus, A Thousand Plateaus), Artaud, Beckett and Genet into Japanese, as well as numerous books and papers on these figures. Two works in particular, Artaud pensée et corps and Hijikata Tatsumi ― Penser un corps épuisé, are available in French.

Find out more about our Deleuze centenary celebrations