2025 marks the centenary of the birth of Gilles Deleuze. Throughout the year, we are exploring the impact of this towering figure in twentieth-century philosophy.

As part of this celebration, we’re publishing a series of blogs from leading Deleuze scholars. Read on to find out how totems in Warlpiri and other Indigenous Australian cultures represent ongoing ancestral connections and ideas similar to those proposed by philosophers Deleuze and Guattari.

Find out more about our centenary celebrations.

By Barbara Glowczewski

In 1974, during my last year of high-school (I was 18), my philosophy professor gave me a copy of Anti-Oedipus to read. I devoured it with a passion. The next year at the University Paris 7, I took a course in the Marxist critique of development and wrote an essay in which I systematically pointed out every time Marx is mentioned in Anti-Oedipus. My professor admitted that my essay prompted him to read Deleuze and Guattari. In 1976 they published the groundbreaking essay ‘Rhizome’ and I enrolled in the course Deleuze taught at the experimental University Paris 8. On this campus built in the woods of Vincennes, in response to the 1968 protests, Deleuze and other radical thinkers drew crowds of fans.

My master thesis in anthropology was supervised by Michel de Certeau. It compared the way different cultures think about the senses and the perception of reality beyond words. When I read that Aboriginal women have a taboo surrounding death that prevents them from speaking for two years, time which they spend in a camp together away from men, I was fascinated and chose to go to Central Australia for my PhD in 1979. I wrote to the Central Land Council, the Aboriginal organisation of lawyers, anthropologists and Indigenous field officers dedicated to manage land issues. They invited me to do my research in Lajamanu with the Warlpiri people who had just won the first land claim. It changed my life.

The dream and the land was the title of my completed PhD thesis in Anthropology (1981). I showed how collective dreaming was at the heart of all cultural transmission, ritual creativity (of paintings, songs and dances) and social organization of the Warlpiri people. They talked about Dreaming laws as feeding all their relationships with animals, and plants, water, fire, wind or stars, what anthropologists called totemism. All these Dreamings formed a rhizomatic network of places connected by songlines all across the continent. Early in 1983, I received a phone call from Guattari who told me that he had just read my thesis and wanted to talk about it because it was very much in the spirit of nomadic schizoanalysis he was developing with Deleuze. I did not quote them much, but my writing must have been – unconsciously? – inspired by my reading of Deleuze and Guattari.

After talking for hours with Guattari about the Warlpiri people, I understood that Deleuze and Guattari had helped me to look at this Australian Indigenous group with fresh eyes. Some of our conversations were published in the Chimères journal they created. I was speaking of territorial mythical and geographical flows, of desire and collective dreams which were anchored in places forming songlines and ancestral stories reenacted through ritual body paintings and dancing. The Warlpiri practiced a collective reinterpretation of dreams through new designs and songs to actualize their spiritual links with specific territories, a perfect example of deleuzo-guattarian ritournelle. My dynamic understanding of these hunter-gatherers was clashing with the classic credo about the Aboriginal people too often categorised as Prehistoric remnants. I developed a topological approach to Indigenous networking of humans and other than humans, beyond a dualistic opposition between nature and culture that was published in 1991 as From dream to law (Du Rêve à la Loi chez les Aborigènes), a book Deleuze quoted in Critical and clinical (1997).

Indigenous Australians’ experience of space, cosmology and social organisation is rhizomatic. The rhizome is not a metaphor but a way of living for these men and women who lived by hunting marsupials and reptiles and digging yams growing in a rhizomatic way. Kangaroo or Yams like all animals and plants are Jukurrpa (Dreamings), that is concepts offering models to live. Totems are not emblems but living ancestors unfolding through generations of humans and more than humans, they are lines of becomings. In other words the cosmology and social life of the Warlpiri (as well as many other Indigenous Australian groups) were embodying some of Deleuze and Guattari theories. It was a time loop, the Warlpiri actualised since time immemorial what their philosophical thinking had virtualised.

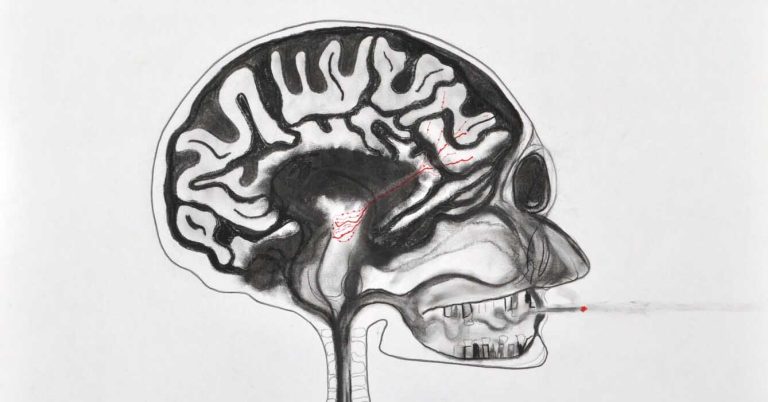

I read Difference and Repetition ([1968] 1995) in 1983 in a book crammed with highlighted sentences and notes in the margins by philosopher of sciences Isabelle Stengers who gave it to me after meeting at Guattari’s seminar. I digested the work very slowly. It was only later on that I understood to how much of what I wrote resonated with the articulation of both these notions. All my work was trying to show that tradition is NOT a repetition but a way of creating every performance as a different event which actualises what is virtual. And the Warlpiri have two concepts in their language to express this: kanunju, underneath, the latent, the virtual and kankarlu, the above, the manifest, the actual. These categories are not exclusive, they work in constant feedback of actualisation and virtualisation, like territorialisation and deterritorialisation.

In the 1990’s, after my marriage with Wayne Jowandi Barker, an Aboriginal film maker and musician from the North West coast of Australia, and the birth of our two girls, we worked on films and coastal land claims of their ancestors, the Djugun and Jabirr Jabirr people. Those years in the Kimberley led me to discover a new Aboriginal universe that resonated with two other concepts present in A Thousand Plateaus: transversality (developed by Guattari through his therapeutic practice as a psychoanalyst) and dissensus. The conflictual debates around the land claim process of this region affected by a very violent colonial past were actually helping in a way to affirm and strengthen the Indigenous people’s anchoring in their lost land.

In Rêves en colère (Dreams in anger), from 2004, I argue that ‘reticular or network thinking is a very ancient Indigenous practice – enhancing the way memory and dreams function for all humans – but it gained a striking actuality at the turn of the twenty-first century thanks to the fact that our so-called scientific perception of cognition, Euclidian space and linear time had changed through the use of new technologies.’ In Indigenising Anthropology with Guattari and Deleuze, from 2020, I suggest that the Internet requires an ecosophical, ethical approach to confront the way algorithms affect our life.

The milieu invites us to turn things inside out, to be affected and traversed by the land, the city, people and all forms of life, even artificial. Despite various criticisms, too often based on misunderstandings of his work, Deleuze stands out as the most insightful philosopher of the 20th Century. His visionary interpretation of the geopolitics of the world, is currently culminating in the fact that in the 1970’s he was already denouncing the genocide of Palestinians he called the Native Americans of Palestine. This colonial parallel he made with the genocidal history of Indigenous people in USA, and their resistance in the name of their belonging to land, is claimed and supported by many Indigenous people across the planet.

About the author

Barbara Glowczewski is an emeritus high distinction senior anthropologist (French National Scientific Research Center). She has been working over 45 years with Indigenous Australians and is involved with current struggles for social and environmental justice. Author of 12 books, including Indigenising Anthropology with Guattari and Deleuze, and over 200 papers in collective books or journals, such as ‘On Indigenous solidarity : Deleuze and the Palestinians‘, in Deleuze and Guattari Studies 19.2.

Find out more about our Deleuze centenary celebrations

To mark the centenary of Deleuze with such a vivid recollection is to remember that thought was never his private property but always a field of intensity — a topology of becoming. What Barbara Glowczewski reminds us, perhaps better than any commentator, is that Deleuze was never “applied” to anthropology; rather, certain worlds were already thinking deleuzianly long before Deleuze existed. The Warlpiri did not illustrate the rhizome — they lived it.

Her narrative quietly inverts the usual hierarchy of theory and fieldwork: it is not philosophy that descends to interpret Indigenous life, but Indigenous cosmology that rises to expose the limits of Western metaphysics. The Dreaming as differential persistence of kanunju and kankarlu is a more radical image of immanence than any conceptual schema of territorialization–deterritorialization.

If the West needed Deleuze to imagine a non-Euclidean life of thought, the Warlpiri had already performed it as law, art, and ethics. Glowczewski’s account shows that the true centenary of Deleuze is not chronological but genealogical: every time a cosmology refuses to separate life from land, or memory from creation, the rhizome thinks again — without a subject, without nostalgia, and without permission.

— Yochanan Schimmelpfennig