2025 marks the centenary of the birth of Gilles Deleuze. Throughout the year, we are exploring the impact of this towering figure in twentieth-century philosophy.

As part of this celebration, we’re publishing a series of blogs from leading Deleuze scholars. Read on for an exploration of how concepts like rhizomes challenge philosophical hierarchies.

Find out more about our centenary celebrations.

By Paul Patton

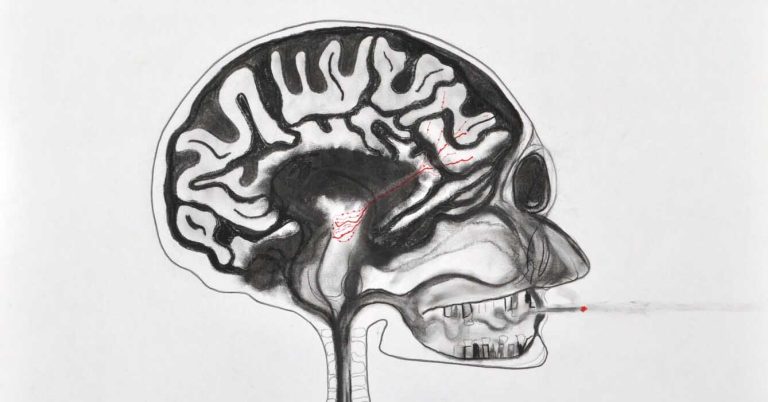

I arrived in Paris in the summer of 1975, fresh from the radical wing of the recently split Philosophy department at The University of Sydney. My interest in French philosophy was almost entirely based on Althusserian Marxism along with a smattering of Foucault, mostly his work on the history of madness and the archaeology of knowledge. Newly enrolled in the Philosophy Department at Paris 8 Vincennes and knowing little of Deleuze I went along to his seminar one Tuesday morning early in 1976. The scene in the small room packed with people and a thick layer of cigarette smoke is dimly preserved in videos recorded for Italian TV and still available on YouTube. I was at once completely mystified – dépaysé in my newly acquired language – and utterly seduced by the low-key rasping monologue at the centre of it all. It talked about the difference between trees and rhizomes, about various kinds of becoming-animal, werewolves, rats and Moby Dick. It provoked a series of questions that continue to inspire my fascination with Deleuze: what was the point of drawing these fine distinctions between different kinds of multiplicity? What does this discourse replete with examples from literature, mythology, anthropology and elsewhere have to do with philosophy?

Deleuze’s lectures at that time were drawn from material that would become A Thousand Plateaus, co-authored with Guattari. Eventually published in 1980, it received nothing like the critical acclaim accorded to their 1971 Anti-Oedipus, which became a talismanic text of French post-68 leftist counterculture. Despite this relative lack of success, Deleuze claimed in an interview published in Le Nouvel Observateur shortly after his death in 1995 that it was the best that he and Guattari did together, indeed, the best thing that he had done. He also insisted in interviews published soon after the publication of A Thousand Plateaus that it was a work of philosophy, ‘nothing but philosophy, in the traditional sense of the word’. My subsequent reading of Deleuze’s work only intensified the question: why was this book, which hardly refers to the history of philosophy much less contemporary philosophers, the best in Deleuze’s estimation? Why this book that develops a bewildering array of new terms to describe phenomena hitherto unknown to the discipline of philosophy: molar and molecular assemblages, lines of flight, faciality, collective assemblages of enunciation, war machines and apparatuses of capture, to name but a few?

After completing my doctoral thesis on the efforts of Althusser and Popper to demarcate science from non-science, I returned to Sydney at the end of the 1970s. In collaboration with Paul Foss I translated the first version of Rhizome, published as a stand-alone text in 1976 before it reappeared in modified form in A Thousand Plateaus. In a series of introductory notes to the translation, published in 1981 in the English journal I&C (formerly Ideology & Consciousness), I presented Rhizome misleadingly as an early version of the ‘Introduction’ to A Thousand Plateaus. Less misleadingly, I also described it as a programme for a novel kind of book, one that embodied a non-hierarchical and a-centred form of knowledge that did not seek to represent the world but to function in connection with parts of it. This early draft of Rhizome played up the pragmatic dimension of the philosophy presented in A Thousand Plateaus. As Deleuze later described it in a short text published in a collection in support of the ‘experimental’ university of Vincennes, this was a practice and a teaching of philosophy oriented towards learning how it might be useful to mathematicians or musicians (or any other cultural practitioner) especially and above all when it did not talk about mathematics or music.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that he envisaged an ‘outward facing’ conception of philosophy in contrast to the ‘inward facing’ conceptions that view it as a discipline that speaks primarily to its own practitioners, whether they be analytic philosophers committed to writing journal articles for specialists in their particular subfield or continental philosophers devoted to canonical texts and the history of their interpretation. This outward facing conception of philosophy has recently been taken up in a quite different context as a response to the institutional pressures confronting the discipline in the neoliberal university. With explicit reference to Deleuze and Guattari, Robert Frodeman and Adam Briggle defend in Socrates Tenured: The Institutions of 21st– Century Philosophy a conception of ‘field’ philosophy that seeks to contribute to solving practical problems in terms that are attractive to the non-philosophers engaged in them.

In Deleuze’s case, the outward facing conception of philosophy emerged in response to a different set of concerns internal to the history of European philosophy. At the centre of his major thesis for the Doctorat d’Etat, published in 1968 as Différence et repetition, was the suggestion that philosophy hitherto had been dominated by an ‘image’ of thought that, in Deleuze’s view, ‘profoundly betrays what it means to think’. In that book Deleuze pointed to the possibility of another image of thought modelled on the activity of learning or apprenticeship, however his own thought took a different path. In the preface he wrote for the English translation, Deleuze commented on the importance of his characterization of the dominant image of thought for his subsequent work with Guattari, in which they invoked ‘a vegetal model of thought: the rhizome in opposition to the tree, a rhizome-thought instead of an arborescent thought’. Reading this, I realized that Rhizome should be read as an outline of the alternative image of thought that this book sought to concretize.

Difference and Repetition is of course one of Deleuze’s most recognizably philosophical works by the normal standards of the discipline. In the view of the Oxford philosopher A. W. Moore it represents, along with Logic of Sense, his most significant contribution to metaphysics, the sub-discipline of philosophy that Moore describes as the attempt ‘to make sense of how things make sense’ (The Evolution of Modern Metaphysics: Making Sense of Things, 554). Deleuze’s own definition of philosophy proposed that philosophers make sense of things by inventing concepts, where this is a term of art for the kind of intellectual object that philosophers produce. In these terms, his preference for A Thousand Plateaus amounted to a preference for applied metaphysics, for the invention of ‘mobile’ concepts that escaped the dogmatic image of thought described in Difference and Repetition in favour of the fluid and open-ended form of organization that he and Guattari called rhizomatic.

A Thousand Plateaus presents an open-ended series of attempts at new concepts: smooth as opposed to striated space, haecceity, becomings-animal, abstract machine, forms of segmentarity and so on. These are not concepts in the traditionally accepted sense of the term: necessary and sufficient conditions for the recognition of certain classes or kinds of thing. They are attempts to trace the characteristics of processes or events that are essentially variable, and to do so by reference to empirical processes or events that are accidental rather than essential to the phenomena captured by these mobile concepts. One doesn’t have to be convinced by each of the attempts to appreciate this extraordinary endeavour. I share Ronald Bogue’s hesitations about the concept of the war-machine while remaining fascinated by the attempt to define a ‘pure form of exteriority’ that is ‘fundamentally different from itself’ (ATP, 354, 352). The understanding and analysis of this extraordinary philosophical project are still in early stages, although the essays collected in Somers-Hall, Bell and Williams’ A Thousand Plateaus and Philosophy make a promising start. It may be some time before chairs in philosophy are created for the interpretation of this work, as Nietzsche famously suggested would happen with Thus Spoke Zarathustra, but there is much that remains to be unravelled. What I stumbled into at Vincennes all those years ago was one of the most original and audacious philosophical experiments ever undertaken.

Find out more about our Deleuze centenary celebrations