by S. E. Gontarski

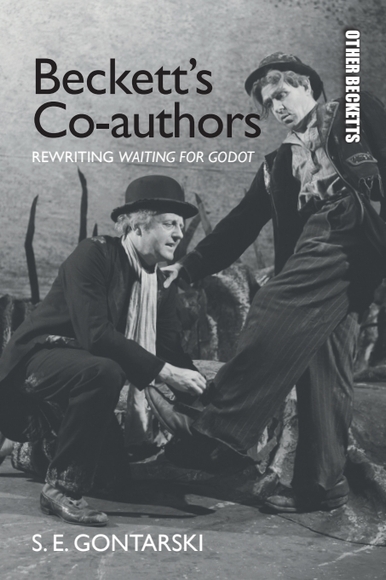

Beckett’s Co-authors: Rewriting Waiting for Godot closely examines the original stagings of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and the point at which theatrical collaboration becomes co-authorship

Where can we find Godot? What’s important here is less answering such provocation than raising it. So – again – where do we find Godot? Such issues are engaged, parced and thrashed about if not resolved in Beckett’s Co-authors: Rewriting Waiting for Godot.

But for now, let’s ask again, where can we find Godot? Not a certain Mr. Godot, of course. That’s the preoccupation of the players, but the dramatic work so called. If we say, rather naively, perhaps, in the object we plucked from the shelf in a bookshop, or from a rack in the supermarket, or we were handed in a drama class, the question remains who created the object we are holding, that is, who wrote Waiting for Godot? The object’s cover and title page bear a name of someone deemed the author, but what confidence should we have in that assignation, especially for a playscript, which only finds its realization in an embodied version of the object we hold. The material we are holding is not theatre. The material in our hand is an incomplete, incipient or nascent artwork, so the next question may be who “authored” the artwork, the performance we may be watching, which, finally, is the completion of the material object we are holding and since all performance is adaptation that realized artwork required collaborators, co-creators of its realization; further, productions are by definition not only co-created but co-authored, sometimes independent of the initiating object.

Where to find Godot, then, depends on what one means by such a question, that is, what authorship means in the theater, for instance, in Shakespeare’s and Ben Johnson’s time and in our own, and to what purposes are words put, to invoke what John Searle would call speech-acts. Searle makes crucial distinction in language between “sentence” and “utterance,” the latter the intended meaning of the former. The same sentence can be used to invoke substantially different meanings.

While textuality invokes materiality, George Bornstein raises questions about the material text in theater:[6] “[. . .] to find Shakespeare’s King Lear we need to turn to the Pied Bull Quarto or the First Folio; [but] on the contrary, those originals of this work of literary art may themselves be inferior copies, either of a lost manuscript or an ideal print version, and themselves full of deficiencies.” It may be hard for us to imagine that the transmission history of Samuel Beckett’s early drama in the mid-twentieth century is dominated by copies “full of deficiencies,” but also of lost manuscript originals, and the overall lack of ideal print versions. Bornstein then leads us into some contemporary editorial theory, that of “multiple authorized versions”: “We need to know what alternate versions to the text we are reading [and staging, we might add] do or might exist [. . .] (Bornstein, 2001, 5).

In Beckett’s case at least seven “Bad Quartos” “full of deficiencies” are in circulation, corrupt publications of the play that have been enshrined in print. Three were published or licensed by Faber & Faber: its ‘timid’ 1956 bowdlerised edition of the play, reprinted in Suhrkamp’s trilingual Dramatische Dichtungen of 1963 — and Faber’s ‘mutilated’ edition of 1956 would reappear 30 years later in its tribute volume, Complete Dramatic Works of 1986. Four further corrupt editions are in circulation (to one degree or another); in addition to the censored and rewritten Samuel French ‘Acting Edition,’ two corrupted versions of Waiting for Godot were published soon after its Broadway premiere, the result of Grove Press’ participation in the standard American theatre machinery that punctuates a work’s Broadway success, the re-publication of important plays in Theatre Arts magazine and in The Best Plays, 1955-56, both published in 1957 with Beckett’s knowledge. And the only sanitized edition of Beckett’s play to be published in the United States was the play’s 1984 re-publication in Literary Cavalcade Magazine: Scholastic Monthly Magazine of Literature and Student Writing.

The embodiment of those versions, that is, theater, adds another exponent to the formula of textual multiplicity. But in Beckett’s era, issues of mechanical textual reproduction enter our textual calculations in that an author’s text is run through a mechanical process that Walter Benjamine saw as diminishing its aura, and if you’ve been to exhibitions of Beckett’s texts, you might be willing to accept Benjamine’s idea that works of art have auras, particularly as we observe their points of initiation: with pen, typewriter or their first printing. In Beckett’s case, such issues are complicated by the technology of mimeography, as both London and so the English premieres of Waiting for Godot in 1955 were staged without professionally printed versions of the artwork produced by official publishers, although those were available to the team staging the English productions, but with altered mimeographed scripts, something of an ad hoc reproductive process.

Some texts for Beckett’s first produced play were, of course, censored, as was the Faber & Faber first edition, others, however, were radically localized for performance, overtly over-written and/or improved to bring them in line with current theatrical standards – some of those were published, and such overwritten and “improved” versions remain in circulation, part of the literary marketplace, serially reprinted and resold. They are seldom withdrawn or destroyed for reasons of corruption or infidelity, and so they remain available, sitting in libraries, on the shelves of drama societies and clubs, in school closets and on personal bookshelves to be lent to friends and reused for performances.

[1] Review: https://www.afridiziak.com/reviews/waiting-for-godot-by-samuel-beckett/

[3] More images and video excerpts at: https://www.lambert-wild.com/fr/spectacle/en-attendant-godot

[4] More details at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Waiting_for_godot_director_alienrezmain.jpg

[6] Bornstein, George (2001), Material Modernism: The Politics of the Page. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

About the author

S. E. Gontarski is Robert O. Lawton Distinguished Professor of English at Florida State University. He has published more than 40 books, including The Beckett Critical Reader: Archives, Theories and Translations (2012), The Edinburgh Companion to Samuel Beckett and the Arts (2014), Creative Involution: Bergson, Beckett, Deleuze (2015), Beckett Matters: Beckett’s Late Modernism (2016) and Revisioning Beckett: Samuel Beckett’s Decadent Turn (2018).