by Tao Peng

Why Do Chinese Readers Like Wang Zengqi?

During Wang Zengqi’s (1920–1997) lifetime, his works were not yet bestsellers in bookstores across China as they are today, nor were there as many academic articles discussing their literary value. Publishers reprint his works with themes ranging from folklore to flora, but the most popular collections are his writings which offer a linguistic table of snacks and other foods. To a large extent, Wang’s fiction provides a lifestyle guide and spiritual comfort to China’s expanding urban population, similar to what 18th-century Romanticism provided to the emerging bourgeoisie of Europe.

Wang Zengqi’s writing career was full of twists and turns. Although he began his literary work in the 1940s, the unexpected course of modern Chinese history did not allow him the opportunity to pursue fiction writing until the early 1980s, when he was in his sixties and formally recognized as a writer.

I was born in the early 1980s, and Wang’s works were not included in our Chinese primary and secondary school textbooks. We read Lu Xun (1881-1936) instead, who offered a critique of the national character of the Chinese people. As a child of a state–factory worker family, who could not have meat with every meal and who hadn’t yet experienced a first love, I once imitated Lu Xun’s tone to write essays criticizing society. What a teenage life that was! In retrospect, it was quite amusing, but this premature political awareness was, in fact, a performance imposed upon me, which I didn’t realize at the time.

In a college literature class in 1999, I read Wang Zengqi for the first time, initially drawn not to his beautiful landscapes, but to his vivid descriptions of snacks. My hunger satisfied; I was later captivated by his prose. I even traveled to Kunming and Beijing to try the foods that he wrote about, tasting for myself his thoughtful and opulent sentences. His writing became my model, as I began to craft my sentences in his fluent and concise way. In China, enthusiasts like me are called “Wang fans”– a term that is simultaneously praise and ridicule. Like the appellation “petty bourgeoisie,” it implies a target for critique or satire.

Why Are Western Readers Unfamiliar with Wang Zengqi?

To Western readers, Wang remains a largely unknown figure, in part because of the scarcity of his works available in English translation, but also because readers find his short stories lacking dramatic conflict. As he explained, he aimed to write “essay-like” fiction, prioritizing the beauty of language over the surprises of plot twists.

Wang’s emphasis on language is difficult to convey through translation. The wild vegetables, mushrooms, and fruits that tempt Chinese readers in Wang’s short stories often translate into tedious plant classifications for English readers.

Wang’s descriptions of the serene landscapes surrounding Buddhist temples are enchanting, but features of East Asian aesthetics, like the rhymed, flowing script of couplets and plaques, become dry and barren statements when translated. The nuanced relationship between these settings and Wang’s characters’ inner life often disappears in English.

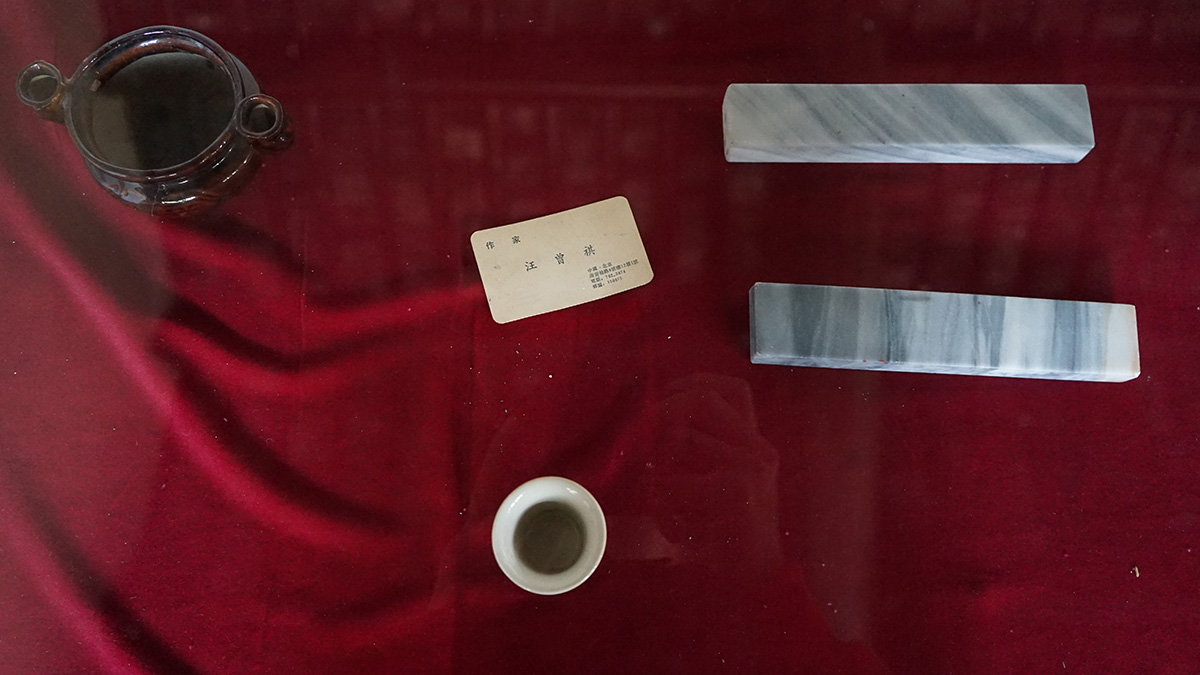

Even from the perspective of Western scholars interested in modern Chinese topics, Wang is not a particularly important writer. His gentle style, understated themes, and lack of critical edge defy expectations of contemporary fiction. In 1988, my doctoral mentor, Perry Link, lived in Beijing and attended a seminar on Wang’s works where he met Wang in person. Although Link deeply admires Chinese language and literature, even he completely forgot about this presentation. It wasn’t until after I showed him a photo of himself at the seminar that Link recalled attending. It’s not surprising—69-year-old Wang was still considered a “new” writer at that time, and his works had yet to receive thorough examination from Chinese literary critics, let alone overseas Chinese scholars.

Why I Wrote an Article on Wang Zengqi in English

Over the last 11 years, I have taught Chinese language at several U.S. universities. My greatest fulfillment comes from guiding a first-year student through the basics of pronunciation and grammar so they can take a seat at Wang’s fictional table. In reading Wang’s original Chinese text, I tell my students that they get to experience authentic Chinese food, but to read Wang in translation is like eating General Tso’s chicken at Panda Express. Through my analyses of Wang Zengqi’s work, I hope to entice my English students and colleagues to translate Wang’s plates of prose. Contrary to the old adage, the more cooks we can invite to Wang’s kitchen, the more his literature can be appreciated.

Read ‘Modernist Techniques in Wang Zengqi’s Fiction from the 1940s to the 1980s‘ in Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 36.2

About the journal

Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) is a peer-reviewed journal for research on literature and other cultural topics, including film, drama, art, dance, performance, architecture, media history, print culture, and regional trends. The journal naturally covers mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, but it is not confined by geographic, ethnic, or linguistic boundaries. Instead, it embraces Chinese culture in a global sense that crosses such divides. This panoramic scope enables it to trace and juxtapose the remarkable shifts and fractures across modern Chinese cultural history, examining how they continually influence current trends today.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases