By Vaughn Scribner

Over the past year, I’ve come to realize just how much “transmigrations” drive my scholarly and personal pursuits.

I study identity and place in the eighteenth-century British Empire. How, my scholarship explores, did early modern Britons position themselves in global networks, while also maintaining a local self? How, likewise, did they transfer and transmit notions of “Britishness” (that ever-nebulous term) as they traveled far from home?

Perhaps not surprisingly, these same questions overlap with my day-to-day experiences—whether enduring the mundanity of grocery shopping or exploring a new city, I enjoy reflecting upon my own position within various spheres of culture, commerce, and connection.

Yet, this convergence of historical research and personal encounter recently came into especially sharp focus as I sipped on a pint in an Edinburgh tavern.

Some context is necessary.

Modern Musings

I’ve led five Study Abroad trips to Great Britain since 2019. Guiding college students on these multi-week trips, where they traverse major cities like London, Edinburgh, and Dublin, visit historical sites like Stonehenge, Oxford University, and Bath, or explore innumerable museums, libraries, and archives, is one of the most rewarding parts of my job. It is also a life-changing event for these young people, many of whom have never left Arkansas, never mind America.

But back to the pint in the pub.

After finally snatching a seat at Edinburgh’s crowded “Jolly Judge” last summer, it occurred to me that, as Americans touring Britain, we were part of a much larger, and longer, continuum of exchange and curiosity. The closes, castles, and cathedrals of Edinburgh would have enchanted American colonists in the mid-eighteenth century just as much as they excited my modern-day American students. Likewise, London’s innumerable amusements and Stonehenge’s mysteries wowed colonists who, like the majority of my Arkansas undergraduates, had only ever visited comparably tiny cities, and never come into contact with such an ancient human site.

Of course, these reflections were hardly groundbreaking. Historians have analyzed this American-British phenomenon in depth, for example Julie Flavell in When London Was Capital of America, and William Sachse exploring why so many colonial Americans considered Britain their true “home” in The Colonial American in Britain.

But there was still something in that intoxicating blend of romanticism and reality that greets any foreign traveler; the nostalgia that follows, and the false realities which one’s mind steadily creates of a past and place that never actually existed.

Peregrinations, Past and Present

This brought me back to my recent article with the International Review of Scottish Studies. In this, I use the life of one Scottish-born immigrant to America, Dr. Alexander Hamilton (1712-56), to uncover deeper and longer currents of imperial connection, nationalistic fervor, and nostalgic melancholy.

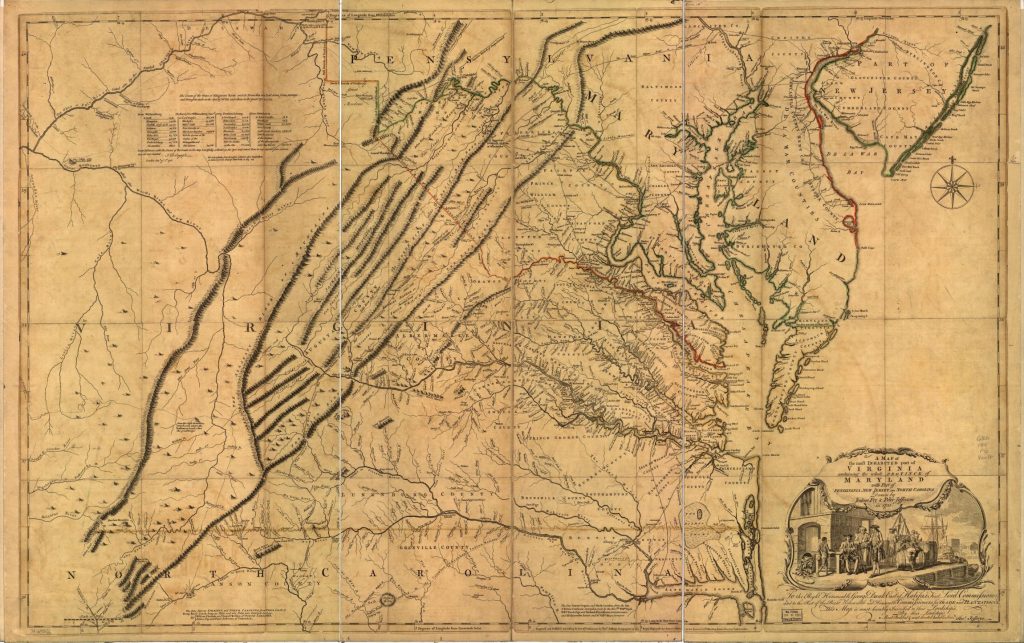

Ironically, Edinburgh’s very success drove the recently-minted doctor, Hamilton, out of his beloved home city. This hub of physicians simply had too many, well, physicians. But Annapolis, Maryland definitely did not. Hence Hamilton’s transatlantic voyage in 1739, after which he ended up in the muddy, half-timbered thoroughfares of Annapolis; a far cry from the gothic cathedrals and cozy pubs of his beloved Edinburgh.

Over the next seventeen years, Hamilton struggled to “transmigrate,” in his own words, the Edinburgh tavern club scene into this “distant and comical corner of the world”: Annapolis. Much like Benjamin Franklin’s love affair with London, however, Hamilton’s vision of Edinburgh—and British society writ-large—was infused with nostalgia for a place that probably never actually existed. The Edinburgh in Hamilton’s mind was perfect; a rosy, ephemeral memory of his youth. Annapolis, meanwhile, came to represent the hard, often disappointing, realities of a far-flung adulthood.

This intoxicating dose of mental and physical separation, along with a double-shot of snobbery, made Hamilton’s attempts at finding Scottish-style, genteel happiness in Annapolis frustrating at best, and absolutely depressing at worst.

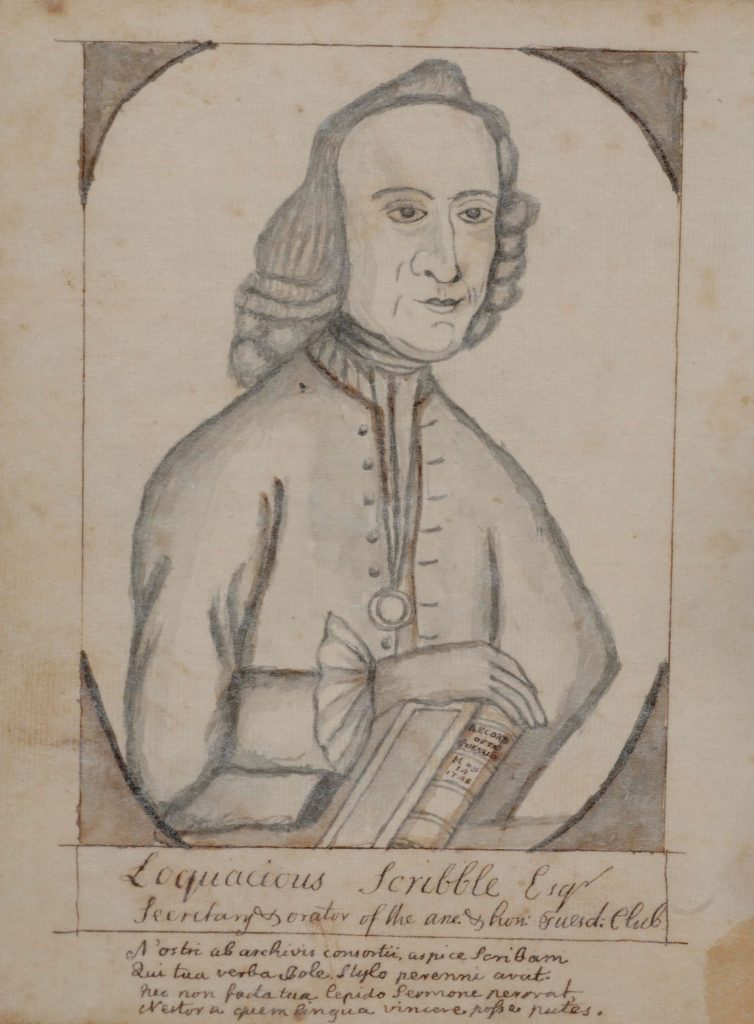

But, as my article shows, Hamilton managed to find some sort of contentment in America. This required a multi-month “itinerarium” through America’s northeastern seaboard in 1744, during which time the Scottish transplant determined that Americans harbored barely enough civility to realize a Scottish-style tavern club, which only he could only operate under his own selective eye. He eventually called this society the “Tuesday Club,” and it became one of the most popular public gatherings in America over the next decade.

Alexander Hamilton’s self-portrait from The History of the Ancient and Honorable Tuesday Club3

Happily, my Study Abroad students are more open than Hamilton to foreign cultures and peoples during their own modern “itinerariums,” even if they do endure the occasional setback or culture shock. But, it is these very transformations—or “transmigrations” as Hamilton called them—which still fuel our curiosity about the past and the present; our sometimes-frustrating, often-fleeting, attempts at connecting with each other and the world around us.

Read the full article, ‘‘Remember Me to All the Members of the Whin Bush Club’: Dr. Alexander Hamilton and the Scottish Tavern Club in America’ in the latest issue of The International Review of Scottish Studies

About the Journal

The International Review of Scottish Studies (IRSS) is the leading interdisciplinary journal for international scholarship on Scottish history and culture, with a mission to create a space for scholars of all career levels exploring Scotland’s past and present.

Sign up for TOC alerts, subscribe to IRSS, recommend to your library, and learn how to submit an article.

About the Author

Vaughn Scribner is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Central Arkansas. He is the author of three books, which cover topics ranging from early American taverns to humanity’s deep obsession with merpeople and, most recently, British and Hessian soldiers’ suffering at the hands of the Revolutionary American environment. He is currently working on a biography of Timothy Dexter, the self-professed “Lord” of early Federal America.

Explore related articles on the EUP Blog

The curious case of Scottish inns, or what travellers sought and found when they encountered them

Emigration from Aberdeenshire and Banffshire

A country built with diasporas and immigrants

Subscribe to our newsletters to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

Image credits:

- The north prospect of the city of Edenburgh. 1702. Mapmaker: John Slezer c.1650-1717. Signet Library maps. License CC-BY-NC-SA. Source: https://maps.nls.uk/view/216390324 ↩︎

- A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. London, 1755. Joshua Fry, Peter Jefferson and Thomas Jefferys. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Control Number: 74693166. Source: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3880.ct000370/ ↩︎

- Loquacious Scribble. Alexander Hamilton’s self-portrait from The History of the Ancient and Honorable Tuesday Club, held at The John Work Garrett Library. Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c9/Loquacious_Scribble.jpg ↩︎