by Naomi Mottram

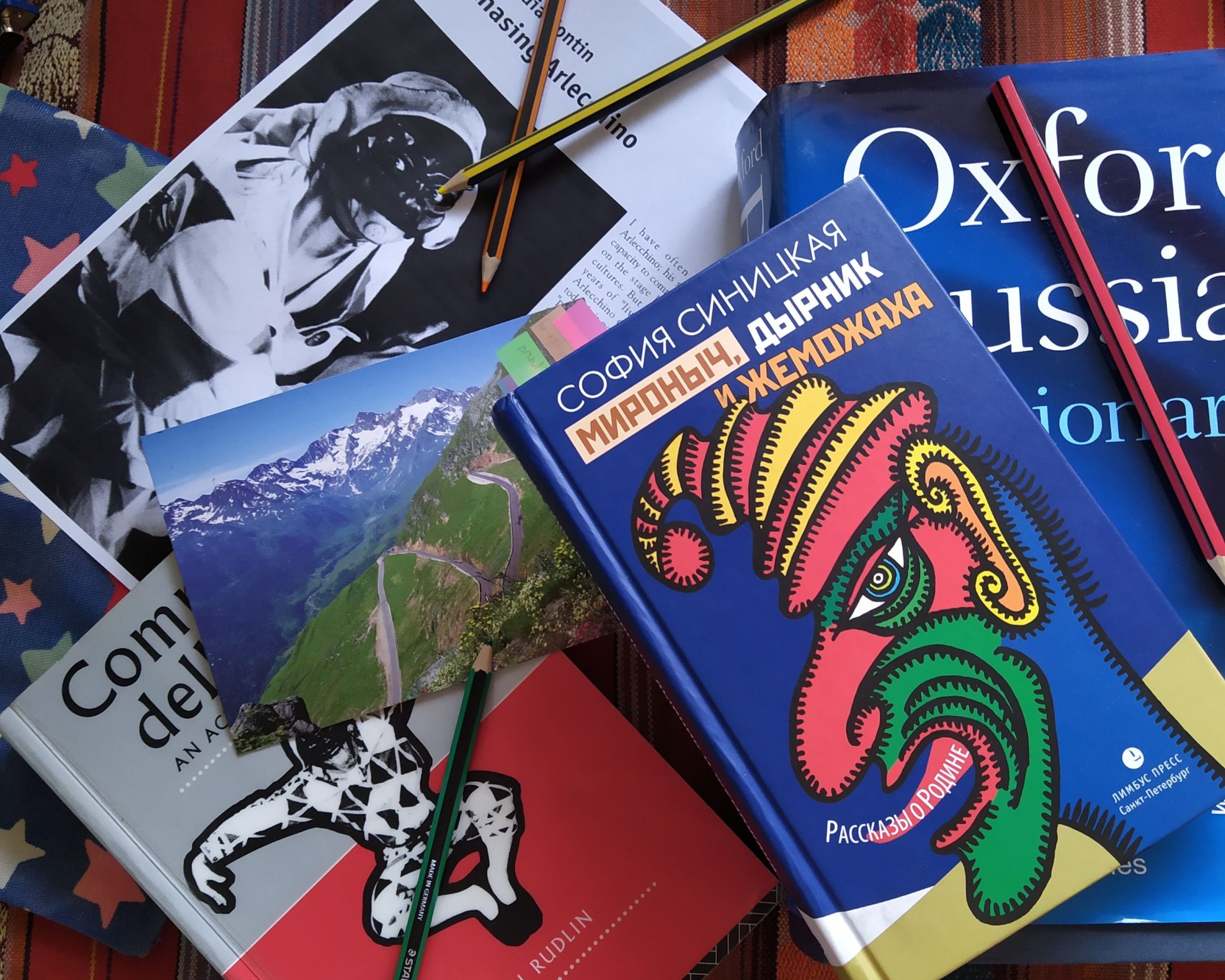

Fans of Commedia dell’Arte know that wherever Arlecchino appears, he causes trouble. So perhaps I should have known that he would cause trouble for me…

While creating my translation of Sofia Sinitskaia’s tale, Mitrofanushka Durasov, which features in Volume 21 Issue 1 of Comparative Critical Studies, one of the most fundamental decisions I had to make was how to refer to the traditional Commedia dell’Arte mask. Should it be the Italian, Arlecchino, or English, Harlequin? You will find that I chose Arlecchino, but why?

At its most basic, this seems like a simple decision between a foreignising term or a domesticating one, but for me it threw up much deeper considerations. We come to literary translation armed not only with our impressive vocabularies and massive dictionaries, but also with knowledge and experience of the surrounding source culture. Even that, though, is not enough. It is necessary also to consider the cultural environment into which you are introducing the text.

My practice is influenced by a view of translation not as a copy or a deformation of the source text, rather, as a part of its continuing life. The text gathers meaning with each reading and interpretation. Working with that principle, instead of focusing solely on representing accurately the features of the source text, I can consider what value each element has in the source, and what value I can create through it for the target text reader.

Why is Arlecchino so important?

Mitrofanushka Durasov is the story of a hapless Russian nobleman in the late 18th century. He becomes enthralled by a couple of Commedia dell’Arte performers visiting Russia from Italy. With them he embarks on a journey to Italy before finding himself abandoned in the Swiss Alps. One of the performers, Pietro, plays Arlecchino; the scatterbrained, intensely emotional, mischievous servant of Pantalone, who is perhaps the most recognisable of the Commedia masks. Performances of Commedia are improvised variations on standard scenarios populated with stock characters. As a result, performers of these masks become profoundly enmeshed with their character (celebrated Arlecchino Claudia Contin’s article Chasing Arlecchino is a good example), some, like Pietro consider him a friend:

‘Pietro stood for a long while staring at the moon which hung low over Konkovo (almost within reach) and at the winking stars. It seemed to him that there was someone very dear to him sitting up there on that silvery orb. A hunchbacked, long nosed someone who fixed his eyes on Pietro whispering urgently ‘Hurry, hurry, the very last ship is prepared…'

And in this story, several characters seem to be strongly associated with Arlecchino. This association even connects the two almost diametrically opposed characters: Pietro, who is clever, strong and successful and Mitrofanushka who is hapless, mollycoddled and childlike. While Pietro plays Arlecchino on the stage, Mitrofanushka seems to embody him in reality.

Why Arlecchino and not Harlequin?

I came to this question with all of these ideas in mind. I wanted the target text reader to associate the idea of Arlecchino with the ancient theatrical form, with his character traits, traditional appearance, and with the stories that surround him. Ultimately, the decision came down to a google search. When I googled ‘Harlequin’, the top results came back referencing everything from rugby to Batman and textile design, whereas the top results for ‘Arlecchino’ returned results relating only to Commedia (with the exception of one pizza restaurant in Scotland). As we sometimes find in literary translation, by using a less familiar term and creating friction for the target reader, I was able to minimise unwanted associations and strengthen those that supported the novelty, exoticism, richness and mysticism of the character.

Arlecchino makes himself known

It seems only fair that Arlecchino should have the last word on how this story not only portrays him, but continues his tradition. Established convention rules that Arlecchino is the only character who can break the fourth wall and speak directly to the audience, and in this story he does this beautifully (and I think with a subtextual wink) through Pietro, who says:

“and sometime in the future, I’m sure of it, some Russian writer will fall in love with Arlecchino and write a brilliant story about him.”

About the Journal

Comparative Critical Studies is the journal for comparative literature as a discipline.

Articles focus on innovative perspectives on the theory and practice of the study of comparative literature in all its aspects, including but not limited to: theory and history of comparative literary studies; comparative studies of conventions, genres, themes and periods; reception studies; comparative gender studies; transmediality; diasporas and the migration of culture from a literary perspective; and the theory and practice of literary translation and cultural transfer.

About Naomi Mottram

Naomi Mottram is a freelance translator specialising in literary and creative texts She gained her bachelor’s degree in French and Russian from the University of Sheffield in 2011 and her Masters in Translation from the University of Bristol in 2021.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases