by Brontë Hebdon

Early in Ridley Scott’s Napoleon (2023), Bonaparte and Josephine de Beauharnais see each other for the first time. Their eyes meet across the room at one of the infamous post-terror bals des victims, and both are immediately transfixed. When Josephine approaches, she gestures to Napoleon’s embroidered coat and asks, ‘What is that costume you have on?’ as if he were disguised for the party. Surprised by her lack of perception, he replies, ‘This is my uniform. I led the French victory at Toulon.’

Although fictional, their interaction demonstrates the reality of Napoleon’s early years in the spotlight, where personal insecurity and the fraught political atmosphere of Paris in the 1790s made many men hide behind their uniforms. Scott and his costume designers, Janty Yates and David Crossman, use Napoleon’s clothing throughout the movie to narrate his political ascension, developing his sense of authority in tandem with his sartorial expression. At three moments – the siege at Toulon, the Coup de 18 Brumaire, and his coronation – his clothing becomes increasingly ornate and colorful, which makes Josephine’s comment prophetic: his uniform was a costume all along.

The Siege at Toulon

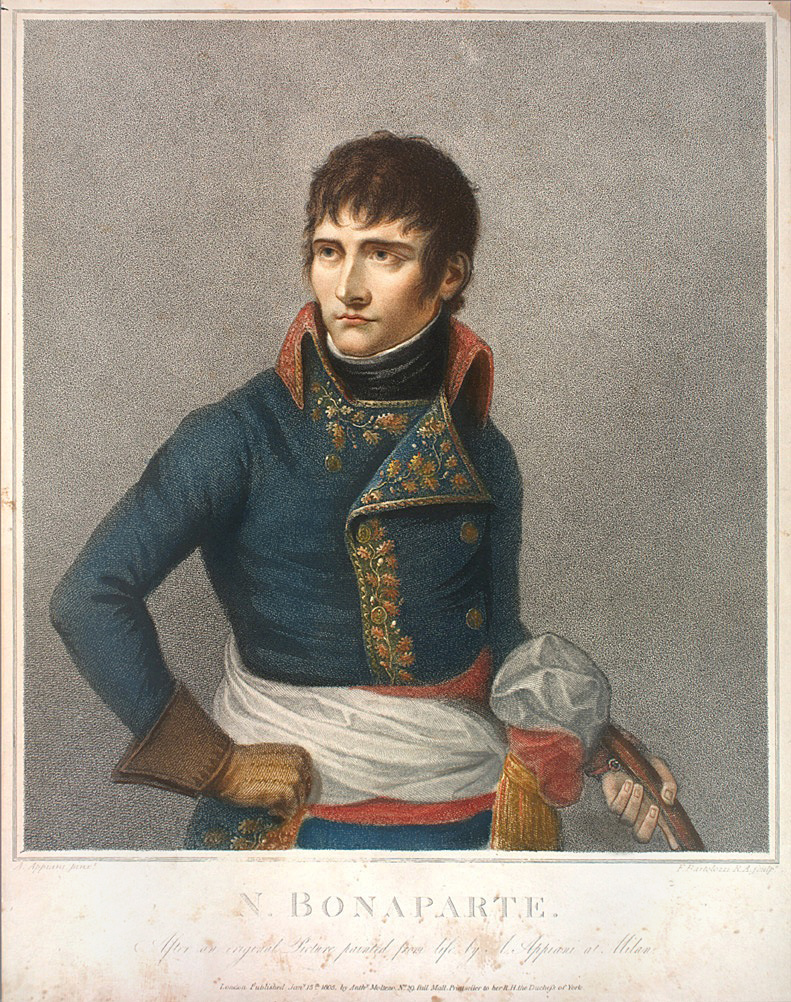

In 1793, royalist supporters in Toulon, a port city in France’s Mediterranean, allowed the British Admiral Alexander Hood to occupy the city. Napoleon’s successful recapture of Toulon that December made him general at only 24, which meant he wore a general’s double-breasted, gold-embroidered coat (cut across the stomach in a style called habit dégagé). As Scott retraces the early years of Napoleon’s military life, the gold embroidery of his general’s coat separates him from the more understated uniforms of his men. The uniform was also a step away from men’s fashion in the 1790s, which, although cut in a similar style, would have eschewed ornamental embroidery as antithetical to the democratic ideals of the Revolution.

The Coup de 18 Brumaire

On 9 November 1799, known in the republican calendar as the Coup de 18 Brumaire, Napoleon and his supporters removed the five-member Directory council from power and instituted a three-person Consulate. In Scott’s retelling, Napoleon appears before the Directory councils in his general’s uniform, but, in reality, Napoleon won the support of the National Guard first by appealing to them dressed in his civilian clothes. He then changed into his general’s uniform to appear before the council.

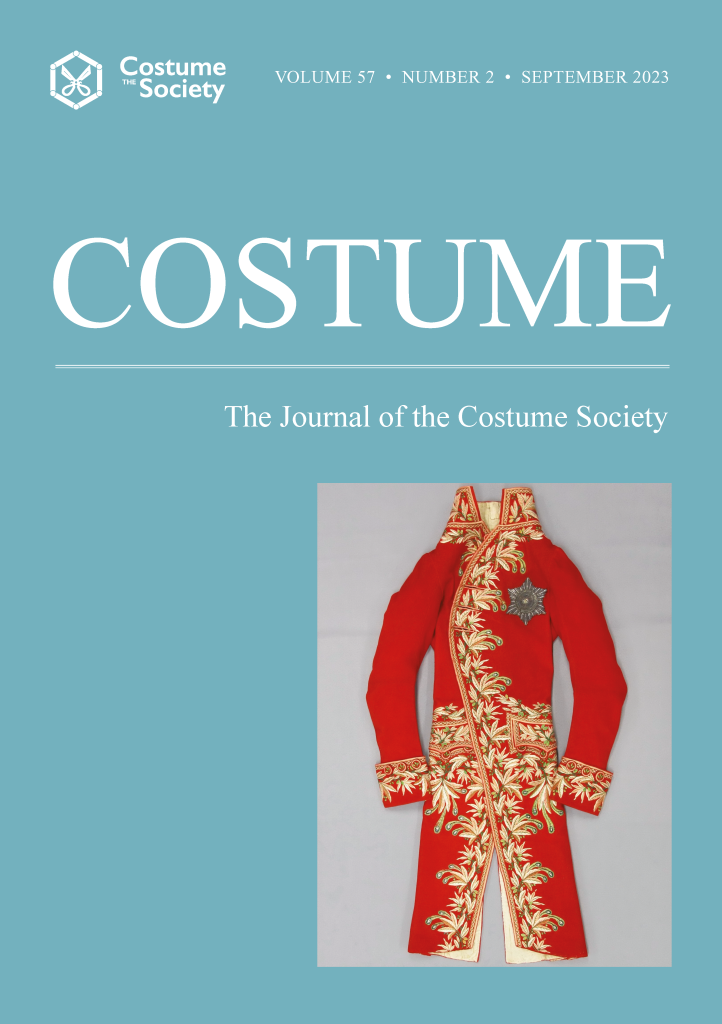

This change in dress supported his change in identity – from civilian to military leader – and with the support of the military, Napoleon’s coup was successful. Almost immediately after gaining power, Napoleon’s government began organizing a system of state uniforms that would similarly transform all men in power. Starting in December 1799, everyone within the Consular government, from mayors and ministers to senators and councilors, received instructions to wear colored coats with embroidery. As First Consul, Napoleon wore a red coat embroidered with gold palmettes. By 1800, the halls of the Tuileries palace were filled with men wearing embroidered coats.

The Coronation

Napoleon’s coronation as Emperor of the French on 4 December 1804 reversed much of the democratic progress of the French Revolution. Once again, the French people were led by a figurehead, so Napoleon’s clothing changed to reflect his new status. The design for Napoleon’s coronation costume referenced the historic coronations of past French monarchs like Charlemagne and Childeric by including a long white tunic embroidered with gold palms and a red velvet mantle lined with ermine and embroidered with bees.

Yates and Crossman faithfully replicate Napoleon’s coronation costume and those of his family members, draping his family and advisors in sumptuous velvets with silver and gold embroidery. Similar to the system of dress developed under the Consulate, members of Napoleon’s imperial court were expected to wear embroidered coats, with the size and complexity of the embroidery signaling the status of the wearer and his position relative to Napoleon. Artist Jacques-Louis David reproduced this social hierarchy of dress in his painting of the Coronation, which hangs today in the Louvre Museum.

And yet, behind the velvet and embroidery, Napoleon still wore his military uniform throughout his political life. The green and red uniform of a colonel of the chasseurs à cheval and the blue and white uniform of a colonel of the grenadiers à pied were his preferences, as was his iconic bicorne hat. Wearing his military uniforms allowed him to move up through French politics until the young, impoverished Corsican aristocrat Napoleon Buonaparte became Napoleon, the general, Consul, and finally, the Emperor of the French. But, as Ridley Scott’s Josephine predicted, Napoleon’s final battle at Waterloo revealed that even his military uniform was, in fact, a costume. Because without the support of the French people, Napoleon’s authority could go no further.

Find out more about embroidered Napoleonic uniforms in the latest Costume issue.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the journal

Costume is the journal of The Costume Society, presenting current research into historic and contemporary dress. The journal publishes articles from a broad chronological period and with a worldwide remit, maintaining a balance between practice and theory with a focus on the social significance of dress.

Sign up for TOC alerts, subscribe to COST, recommend to your library, and learn how to submit.

About the author

Brontë Hebdon is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Her in-progress PhD dissertation examines Napoleonic salon painting, civil uniforms, and embroidery to consider how French court costumes became tools of imperial and cultural conquest in early nineteenth-century Europe.