by Whitney Strub and Peter Alilunas

Tell us a bit about your book

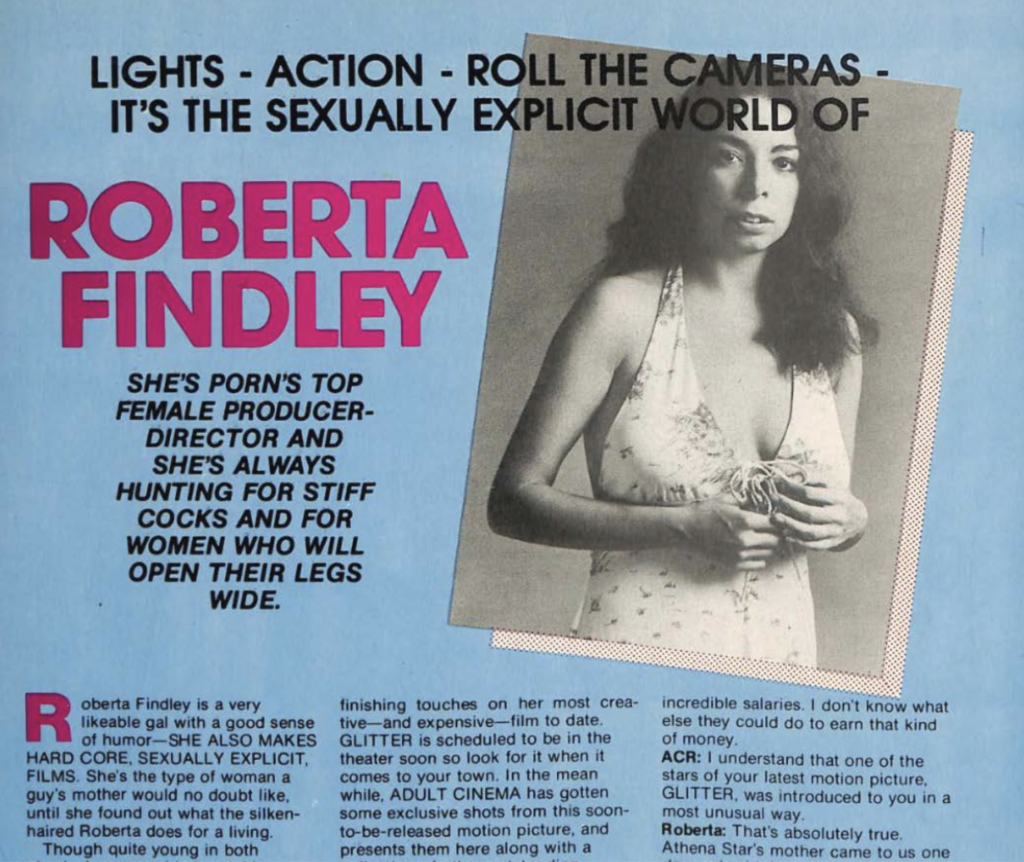

Alilunas and Strub: ReFocus: The Films of Roberta Findlay is the first collection of scholarly essays on the notorious, groundbreaking, iconoclastic, controversial, talented, subversive, and often funny filmmaker Roberta Findlay, featuring an all-star roster of contributors.

What inspired you to research this area?

Alilunas and Strub: We’re both historians of adult film and fans of the ReFocus series, so we tossed around some names. Roberta Findlay provided the perfect figure: a large body of work running parallel to the industrial shifts that filmmaker Joe Sarno helped shape; widespread recognition but limited previous scholarly attention; an opportunity for fresh historical research; and a chance to think about gender and sexual politics from new angles, since she was both a pioneering female pornographer and a distinctly anti-feminist voice whose work often belied her ostensible politics.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

Alilunas: Revisiting these films (and seeing some for the first time) was fantastic. But interviewing Roberta was the sort of career highlight you may only get a few times. That was a memorable thrill – and I was only there on Zoom!

Strub: We occupied a tense and contradictory position – undeniably fans of her work, but also as critics who are not here to blithely celebrate, but rather apply analytical pressure. Her films can be fun, but they’re also unquestionably problematic in numerous ways. Roberta has a reputation as being a bit of a crank, hostile to fans and scholars alike. So it was daunting to walk into Sear Sound studio. Nevertheless, it was a hoot. The studio was lined with posters of her horror films, along with copies of albums I’ve long loved, like Sonic Youth’s masterpiece 1987 Sister. Roberta was open and uncensored, albeit a tad cranky in her assessment of a scholarly book about her work.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

Alilunas and Strub: Along with getting to know Karen Sperling and her film The Waiting Room (1973), which had an all-women crew on which Findlay served as cinematographer, we by pure chance caught that Jean-Luc Godard once used footage from a Findlay film in one of his collage-like essay films. We’ll leave it to readers to comb the footnotes for details.”

Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources?

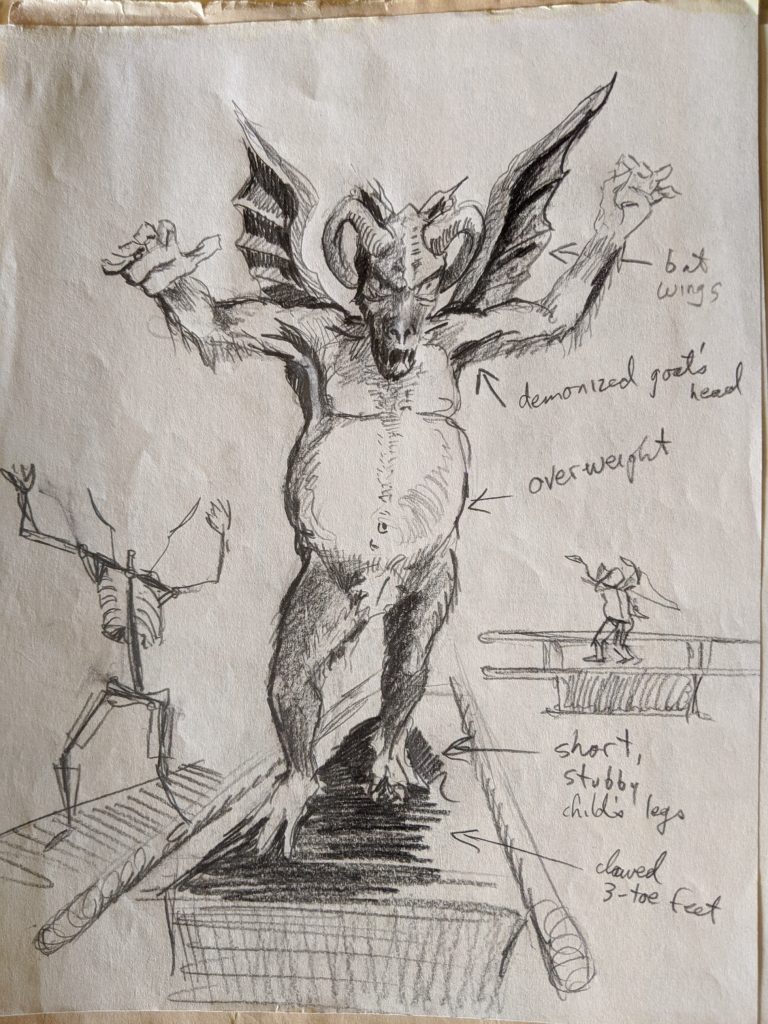

Strub: Roberta insisted that she didn’t keep any diaries, letters, or other such materials that historians crave. But when she casually pointed to the file cabinets in Sear Sound and said, “dig around,” my jaw fell to the floor. There wasn’t much personal/biographical material, but there were reams of business records, the sort of thing historians of adult film almost never find because of how little gets formally preserved. It was too late to integrate into the chapters, but some archive needs to reach out to Roberta, who was quite open to having it properly preserved. We managed to squeeze a few documents into our intro, as a bit of a teaser for future work.

Did your research take you to any unexpected places or unusual situations?

Alilunas: Many contributors Whit and I already knew. The world of academic porn studies is generally a warm and inviting community, but it was a particular thrill to include work by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, who’s probably written the most on Findlay previous to this; Derek Gaskill, who’s a serious porn historian but also happens to be the grandson of Walter Sear, Findlay’s longtime partner and collaborator; and Kier-La Janisse, who was already renowned for her work on cult films but became, at least in my eyes, genuinely famous during the publication process for her stunning epic essay-film, Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror (2021).

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

Alilunas: Film history isn’t a neat, tidy little box into which we can slot every film into in some seamless way. Roberta Findlay really epitomizes that, and challenges how we think about just about every major film-related question of the 20th century.

Strub: Findlay’s films depict a bleak, grim world. They resonate pretty deeply with my general pessimism, which certainly hasn’t been lifted by the events of recent years. At the same time, working on this book, and seeing the creative and brilliant things scholars can do with those films, from Jen Moorman finding glimpses of queer and feminist resistance amidst the general ideological wreckage of the Findlay oeuvre, to Kevin Bozelka unearthing an entire bizarre alternate cosmos in the obscure and ungainly Mnasidika (1969) has just been an endless source of delight and inspiration, and a much needed reminder of the joyous possibilities of scholarly labour. So we can partly thank Roberta Findlay for helping us toggle back and forth between despair and exuberance, and realizing that most of life exists somewhere in that dialectic.

What’s next for you?

Alilunas: Coming soon from me is the Handbook of Adult Film, co-edited with Patrick Keilty and Darshana Mini, and Screening Adult Cinema, co-edited with Desirae Embree and Finley Freibert, both with huge rosters of immensely talented scholars. But on any given night, you can catch me in front of my TV working my way through big stacks of exploitation and otherwise forgotten movies.

Strub: My next project is another edited collection, this one on the LGBTQ histories of Newark, New Jersey, where I live and teach. It grows out of the Queer Newark Oral History Project at Rutgers University that I’ve been involved in since it began in 2011. So, look for Queer Newark from Rutgers University Press in late 2023.

Order your copy

About the editors

Peter Alilunas is an Associate Professor of Cinema Studies at the University of Oregon.

Whitney Strub is an Associate Professor of History at Rutgers University-Newark.