By Stuart Gillespie

I was one of the two founding editors of this journal in 1992. Anyone involved with a publication for this long will have travelled far, and when I look back over the thirty-year lifespan of Translation and Literature (TAL) I see many milestones. One of the constants has been our wonderful publisher, Edinburgh University Press. When we first set out, EUP published few journals, and was nothing like as experienced in journal start-ups as it is now. So, very cautiously, this journal began life as a yearbook. That way, the Press felt, publication could continue indefinitely, but since each issue was little more than a one-off volume, it could also be discontinued without lost investment. The caution proved unnecessary, and we moved to two issues per annum with Volume 4 in 1996. It took until 2011 for us to increase this to three times a year, where it has stayed ever since. Each three-issue volume runs to around 190,000 words, the equivalent of two full-scale monographs. Including Volume 30, a total of 66 issues of the journal have been published.

Online

TAL started out online with Project Muse, but the decisive step was a few years later, with the arrival of Edinburgh UP’s own online journals platform in 2008. This provides the only online access to current issues: other platforms we use, like JSTOR and EBSCO, have embargo periods locking their users out from recent volumes. With our own platform came the ability to collect highly detailed statistical data. This way we can tell, for example, that some very early articles are read online just as much as more recent ones. We can also pinpoint the geographical regions, and even the libraries, where the journal is most read.

For many years now the number of downloads of journal articles and reviews has been rising across all platforms. In part this reflects the simple fact that every twelve months an extra year’s worth of material is available to access, yet the rate of growth is much faster than this factor could account for. Geographical spread explains more of the reason: we’ve noticed a long-term trend towards higher readership everywhere, but especially beyond the Anglophone world.

Reviews

One of the most distinctive things about the journal is the scale of its review section – and the scale of the reviews themselves. Our intention was always to review carefully selected publications in greater depth, rather than add to the number of short reviews many publications receive in academic periodicals. Extending over a remarkable cultural and linguistic range, our reviews are substantial and authoritative enough to be quoted in scholarly publications and cited in footnotes, something which normally happens only with research articles. In 2019 we made free to view all reviews more than five years old. A surge in usage ensued, and the statistics tell us that reviews from many years ago are still heavily read.

Special Issues

There have been more than a dozen special issues over time, usually proposed by a guest editor, who then works with the regular editorial team. Some represent extended treatments of subjects we would ordinarily cover: Versions of Ovid or Modernism and Translation. Others move into territory we might not normally expect to reach: Holocaust Testimony or Versions of Ossian. All their Tables of Contents are on our website.

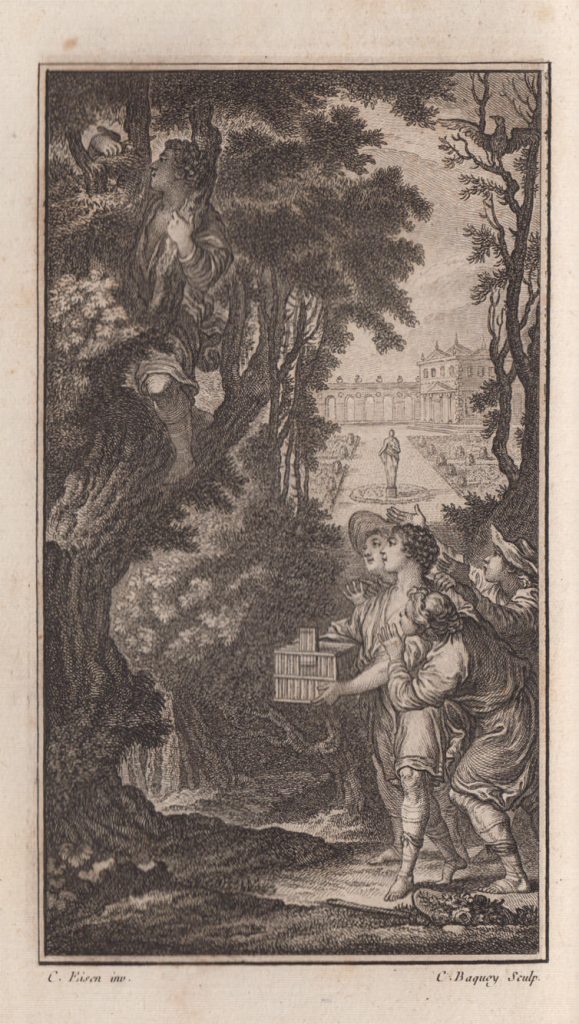

In 2021 we compiled a virtual special issue on Women Translators. This collects in one place some of the contributions published on this subject over the years, and what a diverse group they are. These women belong to every century from the sixteenth to the twentieth, but their work has, of course, never received anything like the amount of attention it enjoys today. At the time of writing, current issues of TAL contain a study of nineteenth-century women’s versions of the Nibelungenlied and an article on Eavan Boland and translation.

The Future

How does a scholarly journal establish itself? My first answer would be ‘by setting high standards’, both editorially and in terms of content. This is a virtuous circle: contributions of high quality will flow in if their authors feel they’ll be appearing in the company of their peers. Today, this flow shows no signs of abating. While familiar ‘classics’ of translation are, of course, staple topics for our contributors, every year we also publish articles and reviews on subjects, and sometimes on languages, which we’ve never touched upon before.

The mission remains unchanged from thirty years ago: we print critical studies and reviews on English literary writing of all periods, including translations into and out of English. Yet we recently found we needed to establish standard fonts to use for printing both traditional Chinese and contemporary mainland Chinese. Over time, I feel, TAL has not only raised the profile of its subject, but helped to extend its boundaries too. The journal will continue to promote the cause of literary translation by treating translation as an integral and indeed essential part of literature.

Stuart Gillespie is Reader in English Literature at Glasgow University. His special interest is the translation into English of ancient Greek and Latin poetry.

Translation and Literature publishes critical studies and reviews primarily on English literary writing, of all periods. Its scope takes in the reception of ancient Greek and Latin works, the historical and contemporary translation of literary works from modern languages, and the far-reaching effects which the practice of translation has, over time, exerted on literature written in English. It embraces imitation and adaptation, including adaptation into other art forms; the theory of literary translation; and publishing history. It also publishes significant historical translations edited from manuscript sources.

See the cumulative index of all articles from Volume 1 to the present here.