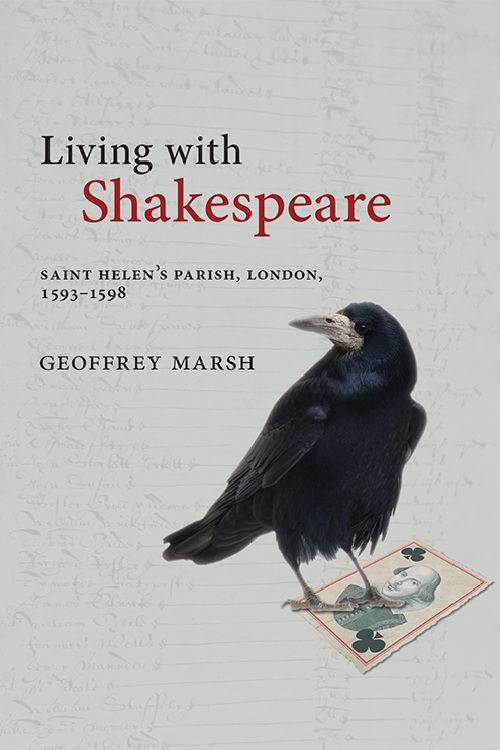

by Geoffrey Marsh

Given that there is little information about Shakespeare’s life, people ask what made me think there was enough to write another book. The short answer is I didn’t. While I would like to claim that Living with Shakespeare was mapped out at the start, the process was far more serendipitous. The following gives a flavour of the route and is also a thank you to some of the people who helped me along the way.

At its heart, my book is about the people who lived alongside Shakespeare in the parish of St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate in the 1590s. We know their names from a 1598 tax record (a ‘Lay Subsidy roll’) that lists Shakespeare amongst forty other English parishioners and fifteen foreign ‘stranger’ families. My research, over several years, went through nine main steps:

1. Initial Curiosity

The 1598 tax record has been known since the 1840s and published several times. However, it appeared that no one had ever investigated the people named alongside England’s greatest writer. I decided to try and find out more about them.

2. First Inspiration

In 2008, Charles Nicholl produced The Lodger, which used a single document, a court deposition by Shakespeare in 1612, to provide an insight into Shakespeare’s life around 1604. If he could do that, then perhaps I might write a ‘prequel’ for the 1590s.

3. Don’t Ignore the People

Parish registers of christenings, marriages and burials often appear dull and uninformative. However, considered sequentially, they can show how families, particularly those with children, evolved over time. I mapped all the records for St. Helen’s from 1576. Suddenly, one could see how families arrived and intermarried. One could identify families that were there in the 1590s, some of whom also appeared on the 1598 tax record.

4. Standing on the Shoulders of Others

Lay subsidy rolls are very intractable documents. Fortunately, Professor Alan Nelson at UCBerkley has transcribed many – thus bringing out of the shadows thousands of otherwise unknown Elizabethan Londoners, many of whom must have seen a Shakespeare play. Without his online transcriptions, I would not have had the confidence to take on these Elizabethan records.

5. The Kindness of Strangers

But what to make of this apparent jumble of names? David Kathman of Chicago provided the key. He shared his work on other tax collections in the next-door parish of St. Ethelburga. His research proves how the collectors moved up and down Bishopsgate Street in a logical fashion. When I applied the same approach to the St. Helen’s records, it was immediately clear that the same method was used. The individuals started to fall into a clear topographical order around the parish.

6. Walk the Ground – Several Times

Fortunately, Shakespeare’s parish church of St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate still survives, and one can explore the interior, including monuments that date back to the 16th century. Alderman John Robinson the Elder was suddenly no longer just a name, one can still view the carved wall memorial to him, his wife Christian and their sixteen children in St. Helen’s.

7. Hope for the Unexpected

I knew that the Company of Leathersellers had owned property in St. Helen’s from the 1540s, but I never seemed to have the time to get to their archive. When I finally did, Jerome Farrell, their archivist, introduced me to their extraordinary records. These included unpublished rent agreements running from the 1550s to the present day and their annual accounts. Suddenly many of the parishioners could not only be fitted onto a parish map but I could identify where they lived and read their rental agreements. Since the names of Leathersellers’ tenants appear on either side of Shakespeare’s name in the 1598 tax record, it seems highly likely that he either was a lodger in a house on their estate or was living very close by.

8. Check, Check, Check Again

Early on, I often missed connections between people which later on were blindingly obvious. Sometimes it was my inexperience of reading Elizabethan records but often it was simply doing research in odd bits of spare time. Slowly the basic names began to evolve into three-dimensional characters, through wills, court cases and other records. Alderman John Robinson the Elder, the respected international merchant on his church memorial, was revealed as a difficult patriarch consulting Simon Forman, the astrologer, fighting with his children and cutting his youngest daughter out of his will for marrying someone he did not approve of.

9. Publishing

But how to get all this information condensed down into a manageable book? That was the easy bit. I was fortunate enough to meet Michelle Houston, EUP’s commissioning editor at a Shakespeare conference in Washington and twenty-four months later Living with Shakespeare came rolling of the presses in Malta. Who knows, if I had not gone to Washington, I might still be researching now…

About the Book

Living with Shakespeare examines his parish, church, locale, neighbours and their potential influences on his writing–from the radical ‘Paracelsian’ doctors, musicians and public figures–to the international merchants who lived nearby.

Geoffrey Marsh is runs the Theatre and Performing Arts department of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. He is the co-editor of David Bowie Is and You Say You Want a Revolution: Records and Rebels, 1966-70.

Enjoy this blog? Check out other similar blogs here.