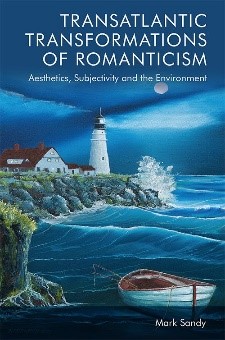

Tell us a bit about Transatlantic Transformations of Romanticism

Well, my book takes a fresh look at the literature of British Romanticism and its influence on twentieth- and twenty-first-century American literary culture and thought. It reads works of prose and poetry from American, Romantic, and post-Romantic writing alongside one another. By so doing, the book aims to deepen our appreciation of Romantic inheritance and influence on post-Romantic aesthetics, subjectivity, and the natural world in the American imagination.

What inspired you to research Romanticism?

Although my primary research interests have been in Romantic poetry, I have always been fascinated by how you can trace the legacies of Romanticism (positive and negative) in the literary culture of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This, coupled with my love of reading and teaching American literature, made me wonder whether the writings of Blake, Byron, Keats, and Shelley were as important to the formation of American literary culture as, say, the writings of Coleridge and Wordsworth. This question stayed with me, especially as I had often felt the presence of these other Romantic writers in the works of Emerson and Thoreau, as well as later twentieth-century American writers. This haunting sense of the Romantic presences of Blake, Byron, Shelley, and Keats in nineteenth- and twentieth-century American writing formed the first seeds of what became this book.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

My research tends to focus solely on Romantic poetry, but this project gave me the chance to explore and write about American novelists, including William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Saul Bellow, and Toni Morrison, who I have read, taught, and admired for many years. The project gave me the exciting opportunity of breaking free of traditionally held boundaries between poetry and prose, as well as strict chronologies, to cast new light on American prose writing through the prism of Romantic poetry.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

Yes, for me, it was arriving at a more fine-grained understanding of those particular works by British Romantic poets that were in circulation in the United States. I knew, for instance, that Thoreau was a keen reader of Wordsworth, but was surprised and delighted to learn that he possessed an edition of The Works of Lord Byron (New York, 1845; originally published 1835).

Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources?

When I was working on the chapter on Saul Bellow, I was fortunate enough to be able to visit the Bellow archive at the Special Collections Center, University of Chicago. I had access there to a wealth of materials, including Bellow’s drafts, manuscripts, and public addresses, which included an unpublished eulogy for his friend and colleague, Allan Bloom.

Did your research take you to any unexpected places or unusual situations?

My research for this book took me rather wonderfully and surprisingly to the heart of Texas. Nestled away in Central Texas, a stone’s throw away from the Brazos River, I discovered the rare nineteenth-century book collection of the Armstrong Browning Library, Baylor University. The library’s architecture has an unexpected charm with its distinctive and beautiful wrought bronze doors, Italianate marble interiors, and iridescent stained-glass windows.

Has your research of Romanticism changed the way you see the world today?

I finished writing this book during the first lockdown due to the COVID pandemic in the UK so, I suppose, whether I wanted it to or not my relationships and interactions with the world were forced to change. The restrictions of lockdown certainly helped to concentrate my mind on the task at hand of finishing the book. But it also confirmed my long-held sense that the Romantics and their treatment of solitary states, the co-dependency of the self on nature, and various crises of subjectivity were as salient to their own times of social upheaval as they are today (and were to my own situation). It pressed home to me that imaginative navigation of subjectivities in crisis during later and equally remarkable historical moments would not have been possible without Romanticism. Nor without, for me, such strongly felt Romantic presences, would this book have been completed in these extraordinary times.

What’s next for you?

My continuing fascination with questions of Romanticism’s bequest and haunting presence in the post-Romantic literary imagination will inform a new book-length study that I plan to write, provisionally titled, Ghostly Presences in Romantic and Victorian Poetics: From Wordsworth to the Brownings.

Image Credits

‘Armstrong browning library baylor 2014‘ via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

About the Book

A critical re-evaluation of the imaginative transformations of Romanticism by major American writers. This book provides innovative readings of literary works of British Romanticism and its influence on twentieth- and twenty-first-century American literary culture and thought. It traverses the traditional critical boundaries of prose and poetry in American and Romantic and post-Romantic writing.

About the Author

Mark Sandy is Professor of English Literature at Durham University. His research interests are Romantic and nineteenth-century poetics and twentieth-century American Literature. His publications include Poetics of Self and Form in Keats and Shelley (Ashgate 2005; Routledge, 2019) and Romanticism, Memory, and Mourning (Ashgate, 2013).

Did you enjoy this blog? Read more blogs on Romanticism here.