In part two of this five-part series, Geetha Ramanathan considers the use of the “ancestral archive” to discuss gender models and sexuality in African American films. Click here to read part one of this series.

Artists from the US, the Caribbean, and Europe have looked to the “ancestral archive” of Africa (I am borrowing the term from Anthonia Kalu, and using it in its broadest sense), and the historical experiences of the diaspora in search of forms of expression as varied as the plastic, dramatic, musical, literary, pictorial, and domestic arts. In each of these arenas, as W.E.B. Dubois and the Harlem Renaissance writer Jean Toomer showed, there was a tradition that artists of newer generations could turn to. In the visual arts, despite the humiliations of minstrelsy in the mainstream US film industry, race films offered complex pictures of African Americans. Models of masculinity, femininity, and sexuality were however constricting, compelling filmmakers to bring to light what the tradition had buried—gay and lesbian sexuality—and in some instances, to invent an archive to draw from. Among these films are:

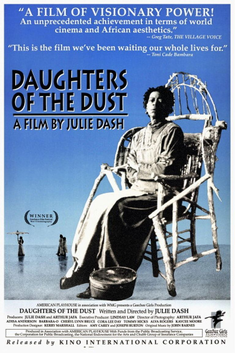

“Looking for Langston” Isaac Julien. UK: Sankofa Film and Video,1989. “Daughters of the Dust” Julie Dash. US: A Geechee Girls Production,1991.

British artist and filmmaker Isaac Julien looked to the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s that resonated with his own moment during the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. Not only was there a new modernist idiom being forged during the 1920s, but ideas of a newer black identity were discussed in Alain Locke’s “The New Negro” (1925). The film reveals a Black gay masculinity, soft and beautiful, in contrast to the ideals forwarded by US and African American mainstream culture.

In the film, Julien grasps at a specific “internationalism” through the gay intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance, who in their self-conscious modernism invite comparison to the euro-modernisms of the 1920s, particularly in regard to “The New Man” envisioned by the Expressionists. The film, while not anti-narrative, evokes the connections made across the generations. The mise-en-scène highlights photographs of Langston Hughes, and James Baldwin among others, and combined with the voice-over readings of poetry encourage the viewer not to be anxious about the what of the film, but to follow what the filmmaker in the opening says is “a meditation on Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance.”

Julie Dash’s films too seek to dig into the “ancestral archive,” never more explicitly presented than in “Daughters of the Dust”, where the action takes place on one day in 1901 when the Peazant family leave the islands off the coast of the Carolinas to come to the mainland. Where Julien connects two modernist moments in gay history, Dash opts for the role of cinematic griot, establishing a link with the African past in the figure of the matriarch, Nana Peazant, who keeps “scraps” of the ancestors. The film is acute about the place of women in this archive, crediting Eula, a woman in the family, with the courage to challenge the Gullah community, and to assume the mantle of the storyteller of their community, their griot, usurping the role of the traditional male griot. In an impassioned speech, she demands that the community respect the woman raped, the woman prostituted. She insists that they recognize Yellow Mary’s (another member of the family) right to bring her lesbian partner to the family reunion. Like Julien’s film, “Daughters of the Dust” finds the past for the present, a record and a reimagining.

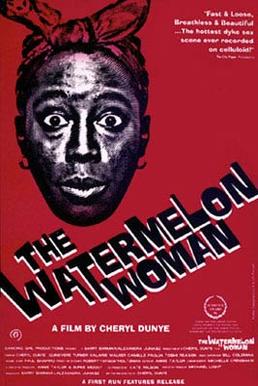

“I am not your Negro” Raoul Peck. USA: Velvet Film, 2016 “The Watermelon Woman” Cheryl Dunye. USA: Alexandra Juhasz 1996.

The search for the “ancestral archive” is many pronged in “I am not your Negro.” First, there is the director who uses documentary footage of interviews James Baldwin had done on television, and then there is Baldwin himself who searches for himself in the Hollywood cinematic canon, and then again through the three black leaders who had been assassinated: Medgar Evers in 1963, Malcolm X in 1965, and M.L.K. Jr. in 1968. The film is structured around Baldwin’s attempts to write a book on the three men even as he felt he was writing the history of the US., maintaining that “the story of the Negro in America was the story of America.” Baldwin’s musings that punctuate the film highlight distorted projections of the national imaginary on a White screen that subsumes blackness and voids Black gay masculinity.

If Baldwin found only images of bleached whiteness, Dunye in her search is compelled to invent the Watermelon Woman for the Hollywood canon. Ironically, the auteur/ narrator longs for the stereotypical image because this indicates Black presence, if as an archetype. What surprises the viewer is that this invented footage is fresh, appealing, and the Watermelon Woman herself, attractive both to the female White star and the viewer. The link between this imaginable, but irretrievable past and the present is a theme that runs through the film as the narrator/filmmaker finds herself unwittingly following the hypothetical plot of the Watermelon Woman’s life.

The films together, along with others, present the diverse ways African diaspora filmmakers have understood the relationship among sexuality, artistic identity, and history.

About the Author

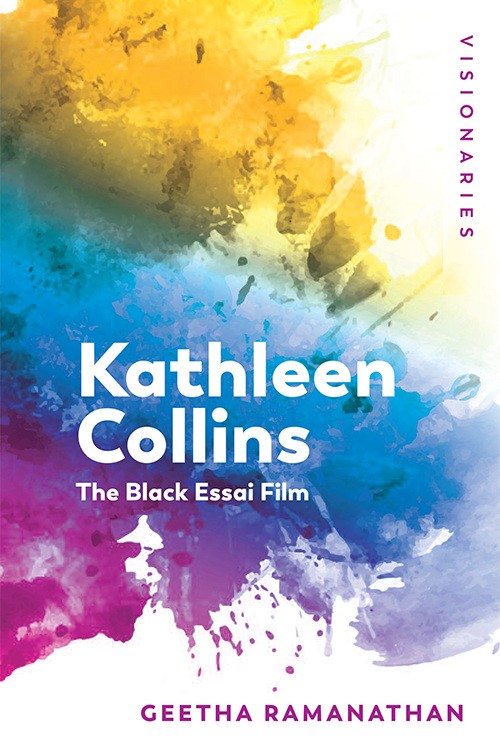

Geetha Ramanathan is the author of Kathleen Collins: The Black Essai Film (Edinburgh University Press, 2020). She is Professor of Comparative Literature at West Chester University where she teaches Comparative Literature, film and Women’s Studies (including Feminist Film and African American Film). Her interests include modernist, feminist and third world literature.