Tell us a bit about Uncommon Alliances: Cultural Narratives of Migration in the New Europe

The book analyses cultural narratives of migration – literature, film, and performance art – which highlight European Union’s neocolonial practices in relation to European history, borders, and guiding ideals of community. It combines postcolonial theory with scholarship on EU multiculturalism in order to understand the current situation of Europe’s non-European and semi-European peripheries and migrants. I argue that the postcolonial theoretical framework itself needs to be revised to account for a structure like the EU, which I describe as a “consensual empire.” The cultural narratives I analyse help us think about the EU as a neocolonial space, but they also explore new modes of transnational affiliation that complicate the politics of the nation and even of multicultural identity groups. They imagine (un)common alliances: subaltern communities unified not around shared identities, but around acting in-common, offering hospitality and friendship to those excluded from European ideals.

What inspired you to research this area?

I was fascinated by the fact that European migrant populations from postcolonial and postcommunist backgrounds are subjected to similar acts of racist discrimination and economic marginalization. The book highlights the many differences between these groups, but also argues that their situations – and stories – should be brought into conversation. They can both be seen as insufficiently European, and in Europe’s neocolonial metropolises as well as in Eastern peripheries, such (non)citizens often have limited access to neo-liberal prosperity, class mobility, consumer goods, or democratic validation.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

I was increasingly coming across literature and films about migration that were difficult to categorise according to nation (e.g. British, British-Nigerian) or language (e.g. Anglophone). For instance, Jamal Mahjoub’s Travelling with Djinns features a Sudanese protagonist who has a Danish wife, travels all around Europe, and meets immigrants from various African backgrounds. Moreover, Mahjoub writes in English but has lived in the Sudan, Spain, Denmark and the UK. What I realized was that EU’s consolidating borders, physical and symbolic, have given rise to narratives that interrogate “Europe” in general and address themselves to migrants from different backgrounds. This is an entirely new phenomenon.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

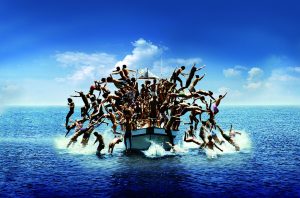

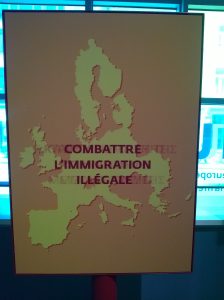

I discovered that EU’s physical borders reach further than I thought: for instance, Spain has two cities in Morocco, Ceuta and Melilla (aside from a number of islands off the coast) which are basically EU outposts on a foreign country’s territory! I was also surprised that much EU scholarship is produced by the social sciences, not the humanities. Perhaps this mirrors dominant perceptions of the EU as a dry, technocratic enterprise, rather than a repository of affective attachments and symbolic meanings, which are usually associated with the member nations and much more interesting to the humanities. But I argue that the EU needs to emerge as a philosophical problem: after all, like any nation, it nurtures idealistic narratives of historical achievement, overcoming adversity, and becoming an example of welfare and tolerance. On the flip side, migrants are treated as a European “problem,” and anti-immigrant rhetoric often insists on defending Europe, rather than just the nation.

Did your research take you to any unexpected places or unusual situations?

Aside from the glamour of attending the Berlinale with a press pass, I toured the EU Parliamentarium visitor centre in Brussels to understand how the EU narrates its history of unification and its relationship with colonial “others” in an official venue. Also, I wanted to visit the House of European History, which would have been even more relevant to this topic, but unfortunately it opened after I completed my manuscript.

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

My research suggests that the current migration to the EU may bring about Europe’s belated, but necessary, confrontation with its colonial heritage. Perhaps this means that the problems of colonialism will ultimately have to be resolved on European soil itself. But as the book suggests, literature and art already provide us with imaginative alternatives to Europe’s neocolonial afterlife – various kinds of subaltern, “uncommon alliances.”

What’s next for you?

I have become quite interested in EU’s extensive, yet invisible, policing of its borders through the use of technology, including radars, cameras, drones, and computers. But undesirable migrants, too, use technology to their benefit, for instance by carrying GPS and cell phones on their journeys. Recent novels and documentaries focus on encounters in these virtual spaces and help us understand how technology can be used both to help and control migrants’ movements. Another area I am researching is the cultural production inspired by the Non-Aligned Movement, which aimed to present a “third way” alternative to Cold War bloc politics.

Nataša Kovačević teaches classes in postcolonial and world literature at Eastern Michigan University. She has published on narratives of migration to the EU, postcolonial and postcommunist literature and film, Cold-War Orientalism, dissident writers, and avant-garde performance art.