By Bill Angus

If you have ever wondered what was really going on in the secret overhearing and tacit observations, the metadramatic inner-plays and devices which Shakespeare constantly revisits, you may have been told that he was ‘playing with the rules of his art’, the great one exploring the parameters of dramatic truth through ‘layers of illusion’. But something more than mere artistic experimentation is happening here.

Drama is most self-revealing at those moments where it reflects upon its own dramatic register, in metadrama, and when Shakespeare, and other early modern writers, use such devices they cannot help but configure within its mechanisms of interpretation the dark connections between themselves and the authorities which define them as writers and subjects. And when they do this a character emerges from the shadows: the despised figure of the informer.

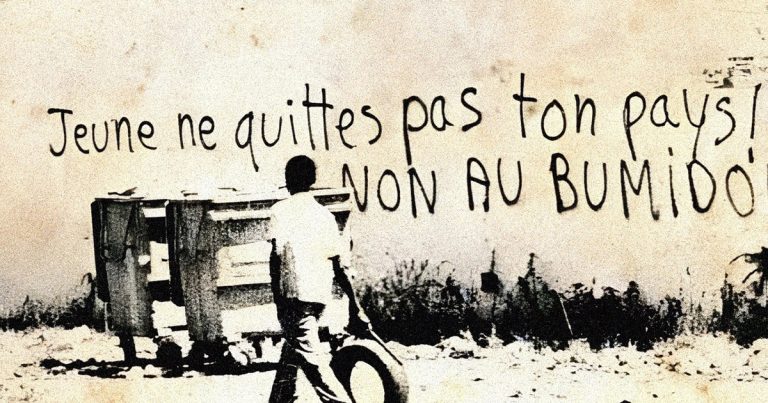

It is a curious fact that the proliferation of metadramatic structures in early modern theatre coincides with an increasing sense of the ubiquity of the informer in society. An early modern audience would be highly aware that some among them would be involved in forms of informing on neighbours, smugglers, traders, political climbers and so on. Informers came from all social ranks, in search of the potentially substantial remuneration their activities might earn within networks of patronage which took for granted, and in a sense formalised, the collection of information.

These widely-reviled figures fed the royal administrations and other local authorities with information on every aspect of contemporary life, from the content of dramatic performances to the correct pannage of pigs or the activities of smugglers and recusants. Far from being exclusive to the spymasters of the Crown, any person of power and influence might expect a flow of information from such individuals. The Earl of Essex, for instance, employed his own expensive and extensive informing network. In an era often of great need there were always those potentially at the ready with information for sale.

This hauntingly present informer is the epitome of metadramatic characterisation, often simultaneously melancholic, Machiavellian, and malcontented. One only needs to think of the impact of Iago, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Jonson’s Sejanus and Mosca, or Webster’s Bosola to understand how compelling a character the predatory informer can be onstage. He is both parasitic plotter and maker of tragedy, and also therefore functions as a shady representation of the author.

At the core of metadramatic devices there is often an uneasy sense of common practice between informers and authors that can cause authors to protest too much about their distinctive qualities. Equally, authors may use metadrama to offer an audience the perspective of the informer as a negative model for their own interpretative practice, allowing some possibility of defensively shaping an audience’s response. Ben Jonson is often found using this mode, although Shakespeare also manifests concern over interpretation in the metadramatic interplay of his dramatis personae.

Hamlet’s informer figures, for instance, generate a duplicitous atmosphere which is integral to the narrative. It is so much the very air that Denmark breathes that the court’s ubiquitous ‘espials’ come to seem ‘lawful’. Hamlet arrives at his and Claudius’ denouement as if on a tide of circumstance, but is in fact lashed there by a perfect storm of informing and duplicity. The metadramatic carnage of the play’s ending, meanwhile, has a tale to tell about the fate of such a society. Conversely, in the metadrama of The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, relatively beneficent authorities oversee the inner action and their informing agents Ariel and Puck act with playful mischief towards their victims, rather than with insidious paid malignity. This is a dramatic and social ideal. Falstaff’s jocular metadrama addresses these pressures in a popular format that involves informing and self-counterfeiting, and links them with the performative aspect of authority reaching to the king himself. If we compare this with the struggles of a character like Coriolanus we may see how an impossible ideal of authoritative authenticity contrasts with the realities of statecraft, intrigue, and expediency.

Although there is some value in thinking through the uses of illusion and the concept of dramatic truth in Shakespeare, the study of his metadrama is nevertheless in need of reconceiving in these far more concrete historical terms. To understand the mechanisms and motivations of his metadrama thereby should allow us to understand this most seminal of authors in a new way.

Bill Angus is  Lecturer in Early Modern Literature at Massey University, New Zealand, where he moved in 2013 after teaching for ten years at various UK universities. His main research interest has been in the metadrama of the period. He is currently researching the conceptual metaphor of the crossroads as a site with transformative power, a place of spiritual binding and loosing, and a space between worlds, in early modern and other cultures.

Lecturer in Early Modern Literature at Massey University, New Zealand, where he moved in 2013 after teaching for ten years at various UK universities. His main research interest has been in the metadrama of the period. He is currently researching the conceptual metaphor of the crossroads as a site with transformative power, a place of spiritual binding and loosing, and a space between worlds, in early modern and other cultures.

Metadrama and the Informer in Shakespeare and Jonson will publish in October 2016.