by Marit Grøtta

Two portrait photographs (visiting cards) of Marcel Proust from 1891 (Wikipedia Commons)

Tell us a bit about your book.

Reading Portrait Photographs in Proust, Kafka and Woolf studies a specific motif in modernist literature: the act of looking at portrait photographs. It shows that Proust, Kafka and Woolf frequently depict scenes in which their characters engage with portrait photographs in emotional ways; they are attracted to such pictures and try to connect with the person in the picture, but at the same time, they are frustrated by the difficulty of reading faces and the problem of the unreturned gaze. The book analyzes these ambivalent responses to portrait photographs in light of the changing media landscape in the modernist period. More broadly, it discusses how the modernists started to live with mediated faces and how the increased circulation of such pictures changed the boundaries between the private and the public spheres.

What inspired you to research this area?

I was intrigued by some very interesting scenes involving portrait photographs in Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time. As I discovered that this motif was recurrent also in Kafka and Woolf, I started to think about such scenes as modernist “media labs” in which various responses to photographs were studied. Further, I realized that these three writers all had a soft spot for such pictures in their private lives: Proust kept an album of portrait photographs by his bed, Kafka exchanged portrait photographs with his fiancé Felice Bauer, and Woolf was surrounded by portrait photographs in her everyday life. I found this attraction to portrait photographs quite touching and started to think about how we relate to such pictures today. As I had previously worked on Baudelaire’s relation to the media, this project seemed a natural step.

Picture from Virginia Woolf Monk’s House photograph album. Angelica Garnett, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes and Lydia Lopokova sitting outside. (Wikimedia Commons)

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

For me it was exiting to explore photography in relation to faces. Today, we are used to mediated faces on Zoom, Instagram, and Facebook, but the modernists witnessed the early phase of technical images and mediated faces. Reading these writers, we start to understand how they struggled to come to terms with this new way of seeing faces. I wanted to highlight the complexity of this experience. In visual studies, photographs and faces are often studied in a critical perspective but in my view, we should also reflect upon the attraction of portrait photographs and the inscrutability of faces.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

Proust, Kafka and Woolf depict very physical ways of engaging with portrait photographs: not only touching them and holding them between one’s hands, but also kissing them and spitting on them. This affective way of relating to a medium could perhaps be seen as heralding our affective relation to the smart phone today.

Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources?

The writings of these modernist giants are well known and well researched, but I found more material related to portrait photographs than I had expected. I also found some interesting paragraphs by Proust that were not included in the published version of In Search of Lost Time; they depict how the narrator studies photographs of Albertine and is puzzled by them because she appears as a stranger. These paragraphs are fully available today but have largely been overlooked in the current research on Proust and photography.

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

I have become very fond of the conventional genre of the portrait. I find the self-relation that is created in a portrait captivating, especially the “look” and the way it can be withheld. I also have a different way of thinking about faces – it is fascinating how a face has no point zero; there is always something going on in a face.

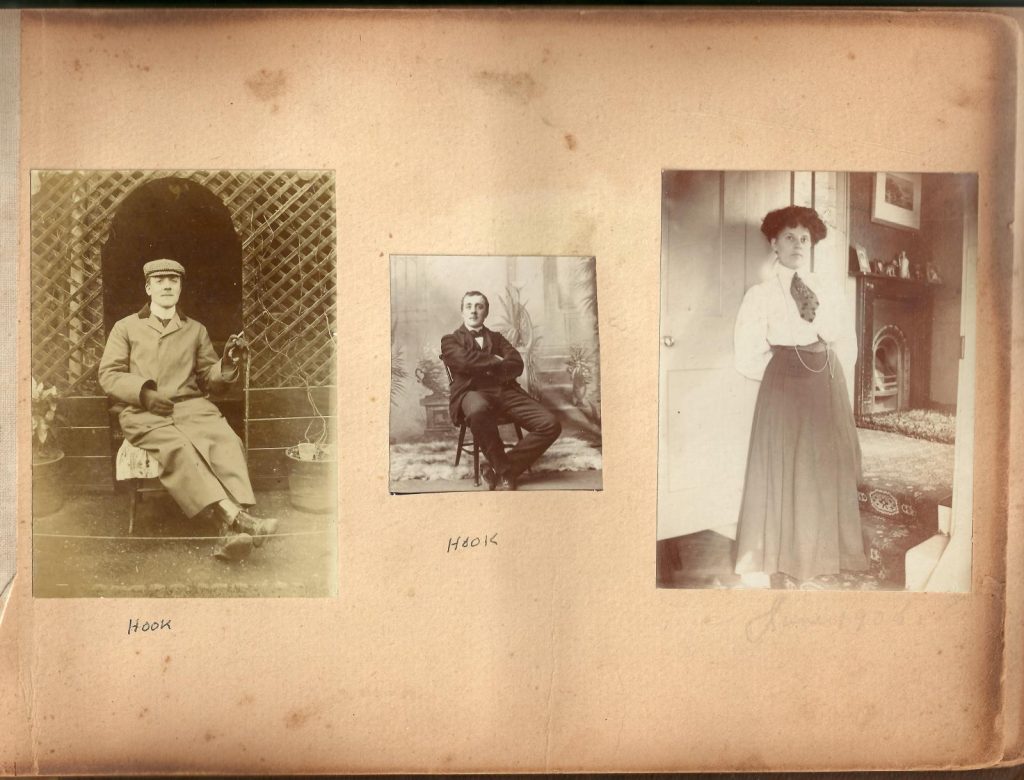

A page from an Edwardian family album (the Hook family album) (Wikimedia Commons)

Did your research take you to any unexpected places or unusual situations?

I have spent time at the National portrait galleries in London and Washington D. C. Further, I have learnt about the horrible history of lynching photographs, which Kafka alludes to in his novel about America, The Man who Disappeared. There is obviously a politics to faces and portraits: whose faces are visible in what contexts; whose faces are named and who remain anonymous?

What’s next for you?

I am currently writing an article on Rainer Maria Rilke and his ways of depicting faces and hands. Rilke is astonishing – he opens so many doors.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the author

Marit Grøtta is Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Oslo, Norway. She is the author of Baudelaire’s Media Aesthetics: The Gaze of the Flâneur and Nineteenth-Century Media (Bloomsbury Academic, 2015) and a number of articles on Schlegel, Baudelaire, Proust, Kafka, Woolf, Queneau and Agamben. Her research interests are nineteenth-century and modernist literature, visual culture, media philosophy and aesthetic theory.

About the book

Reading Portrait Photographs in Proust, Kafka and Woolf examines how portrait photographs appeared as literary motifs in the works of three modernist writers with personal experience of the medium: Marcel Proust, Franz Kafka and Virginia Woolf. Combining perspectives from literary, visual and media studies, Marit Grøtta discusses these writers’ ambivalent views on portrait photographs and the uncertain status of technical images in the early twentieth century more generally. In reconsidering the attention paid to analogue photographs in literature, this book throws light on both modernist reactions to portrait photography and on our relationships to photographs today.