by Rachel Bennett and Lauren Darwin

This article examines the spaces in which the bounds of criminality, the definition of punishment and the distinctions between English and Scots law were played out—namely, the courtroom, the transport ship and the penal colony

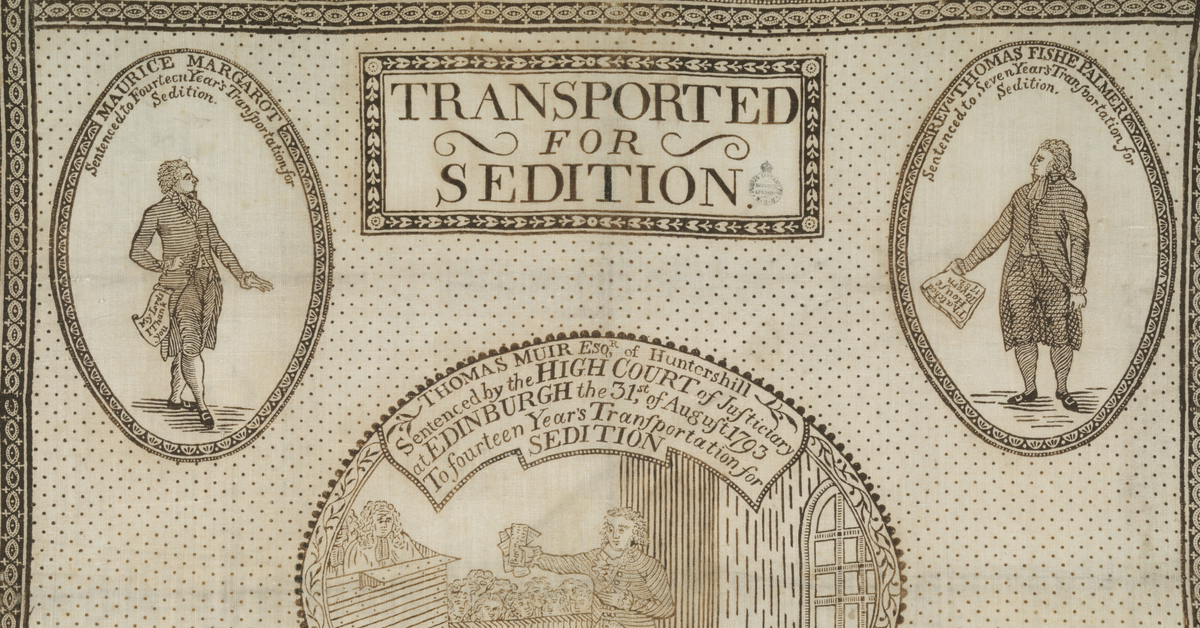

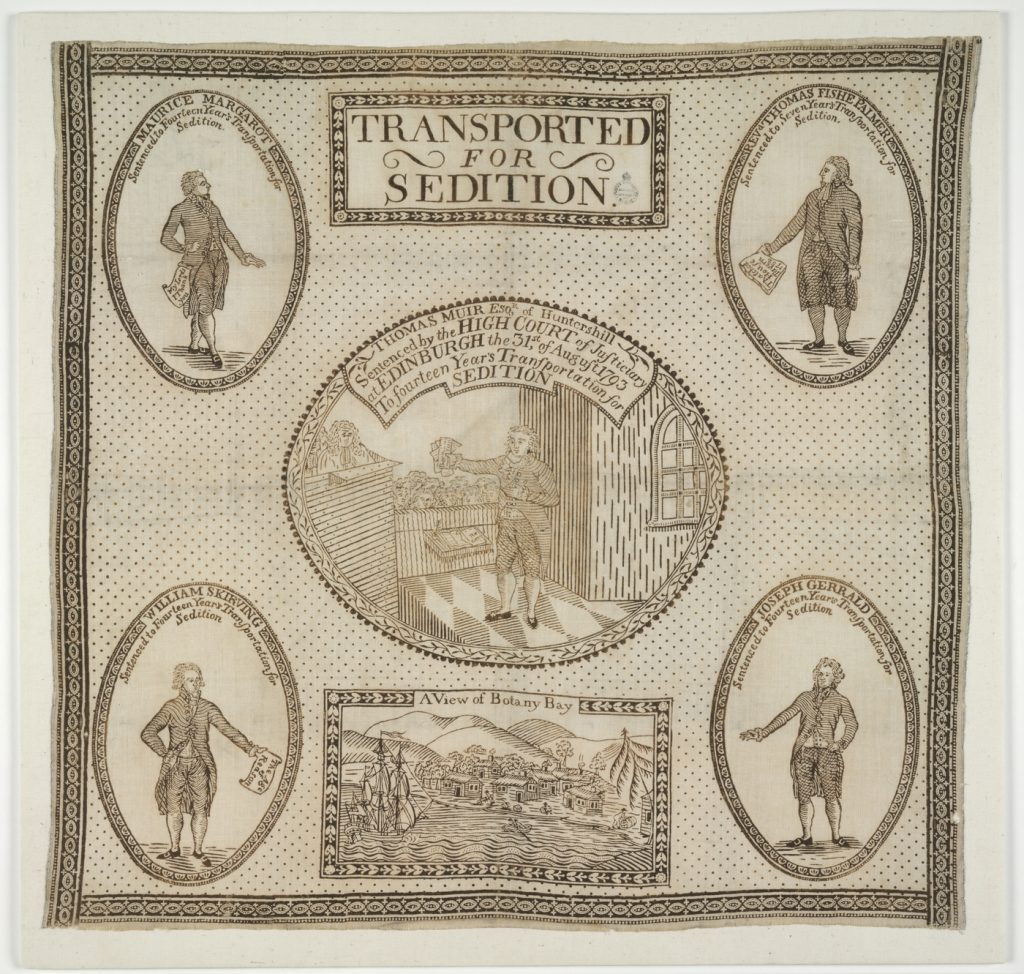

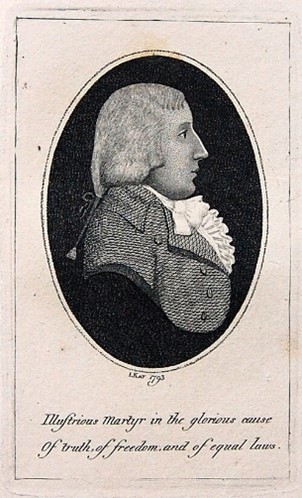

Thomas Muir, Thomas Fysche Palmer, William Skirving, Maurice Margarot and Joseph Gerrald occupy a central thread within the tapestry of Scottish history. Collectively known as the Scottish Martyrs, their support for parliamentary and constitutional change has been commemorated and drawn upon over the last two hundred years to symbolise Scottish liberalism, nationalism and political reform.

In 2014, the history of the Scottish Martyrs was levied within the Scottish Independence Referendum by the ‘Yes’ campaign to add weight to calls for greater Scottish political autonomy. Furthermore, two centuries after his expulsion, in 2020 Muir was restored to the Faculty of Advocates spurring on calls for a posthumous pardon. Thus, it certainly appears that Muir was right when he warned the jury, the records of this trial will pass down to posterity. When our ashes shall be scattered by the winds of heaven, the impartial voice of future times will rejudge your verdict.

Their trials and transportation to Australia have been regarded as one of the great injustices of the Scottish legal systems. However, the jury is still out on whether such injustices should indeed be addressed or left in the past.

Much like the contemporary rhetoric around the Scottish Martyrs, their transportation to the Australian colonies was shaped by the political context, swelling support for reform and state encroachment upon Scottish autonomy. These themes are explored within our article – which provides a clearer picture on how complexities between Scots Law and British penal practice played out to ensure a unique journey for the Scottish Martyrs as they moved through the legal system – highlighting injustices and the true nature of their sacrifice.

The Courtroom: Sedition or Leasing-making?

In Scots Law the crime of sedition, for which the Scottish Martyrs were prosecuted, was not recognised. In England a defendant could be prosecuted for the crimes of ‘seditious libel’ and ‘seditious words’. However, no statute in Scots law covered sedition and there were no former trials for this specific crime in Scotland from which precedence could be drawn. The only crime for which the reformers could have been tried under Scots Law was leasing-making, the punishment for which was banishment. However, as the state wished to make an example out of the Scottish Martyrs and other ‘revolutionaries’ they were tried for sedition, which not only had to be proven but which bore the punishment of transportation. The difficulties of trying the Scottish Martyrs for the crime of sedition were raised at the time (and have been highlighted subsequently).

The Hulks: The Illegal detainment of Scottish convicts

While awaiting transportation, Muir and Palmer were taken to the ‘hulks’, or prison ships. As our article exposes, the detainment of Muir and Palmer, and of all the Scottish convicts taken to the hulks moored in Plymouth and along the River Thames, London between 1787 and 1794 was illegal. While an Act had been passed to ensure that convicts could be detained on board the prison ships, its renewal did not extend to Scotland. These findings are not only important to understanding the journey of the Scottish Martyrs, but also the experiences of other convicts, who were removed from Scotland and lived out their sentence or died on board the hulks during this timeframe. Subsequently, Acts were passed to rectify this issue further aligning possible places of detainment in Scotland and England. However, it is now clear that Muir and Palmer, among other Scottish convicts, should never have endured imprisonment on board the Hulks.

The Suprize: Imprisoned passengers or convict transportees?

Importantly, unlike other convict transportees sent to the Australian colonies, the Scottish Martyrs were allowed to pay for their passage across the seas. While not unusual for convicts sent to the Americas, this practice was uncommon among those transported to Australia. The ramifications of this payment meant that the government had no claim to the service of the Scottish Martyrs and it allowed them to be positioned much like free passengers while on board, sharing some of the same liberties and spaces as free men, rather than be held with other criminals. It was not until Palmer and Skirving were implicated in a plot to take the ship that their liberties were restricted. However, they were still not placed with the other convicts and were not punished like the other mutineers. Throughout their journey through the legal system, but particularly on board the Suprize, it became clear that officials feared a backlash from the Scottish Martyrs’ ‘friends’ at home. Before their voyage, a great sum of money had been raised and sent with the reformers to help them to start a new life in the colonies, evidencing their support at home.

The Australian colonies: Banishment or Transportation?

In Australia, further questions around the conditions of the Martyrs’ punishment surfaced. Muir, Palmer and Skirving asked the Governor of New South Wales, John Hunter, to clarify whether they were at liberty to leave the penal settlement. From their perspectives, in accordance with Scots law,

the extent of our punishment is banishment. The mode of carrying the punishment into effect is transportation. The penalty imposed upon breach is sentence of death.

The reformers argued that the terms of their punishment had indeed been met, and that they should not be made to stay in the Australian colonies. This view was of course rejected by officials in Britain, and it was judged that they had to fulfil their sentence in the penal colony. Muir however, had other ideas and escaped onboard the Otter in 1796.

For the people

The price paid by the Scottish Martyrs in their quest for political reform was exponential. The contentions between Scots Law and British penal practice shaped their journey and although leniency could have been exercised at various points, it was not. Skirving and Gerrald died in Australia in 1796. Muir had an eventful journey after he escaped, but he died in 1799, never setting foot back on Scottish soil. Deciding to depart the colony after he had served his term, Palmer died in 1802 in Guam, while trying to get home. Only Margarot returned to Britain, where he once again advocated for reform and added his voice to discussions of transportation before his death in 1815.

The sacrifice of the Scottish Martyrs lives on through their legacies as they haunt political discourse which is often influenced by the same contentions as their trials and transportation.

Final words

The final words on the Scottish Martyrs should go to Dick Gaughan from his song Thomas Muir of Huntershill:

Gerrard, Palmer, Skirving, Thomas Muir and Margarot

These are names that every Scottish man and woman ought to know

When you’re called for jury service, when your name is drawn by lot

When you vote in an election when you freely voice your thought

Don’t take these things for granted, for dearly were they bought

About the authors

RACHEL BENNETT is a historian of crime and punishment in Britain between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries. She has published widely in areas including capital punishment, the treatment of the criminal body and health in English prisons.

LAUREN DARWIN is a historian of coerced migration, including the British slave trade and convict transportation. She has published and contributed to public history in these areas and is currently a lecturer in History at Newcastle University.