by Denise Wong

Shame in Contemporary You-Narration: Time, Gender and Race argues that temporality and affect are critical dimensions of the proliferation of second-person narratives in the twenty-first century.

Tell us a bit about your book.

Shame in Contemporary You-Narration is a book that explores the proliferation of second-person narrative forms across fiction, film, television, and experimental life writing in the twenty-first century. It makes the case that shame and temporality are central to second-person narration, especially in cases where we have a narrator/protagonist who is addressing or referring to themselves in the present. In the book I call this ‘autodiegetic you-narration’ and explore how it formalises Jean-Paul Sartre’s description of the phenomenology of shame as well as what Mark Currie, building on Martin Heidegger, has described as the structure of the present as the anticipation of retrospection. Put simply, when a narrating-I addresses their past self in the present, it seems to take the present as an object of past narration – as if the present is already past.

What inspired you to research this area?

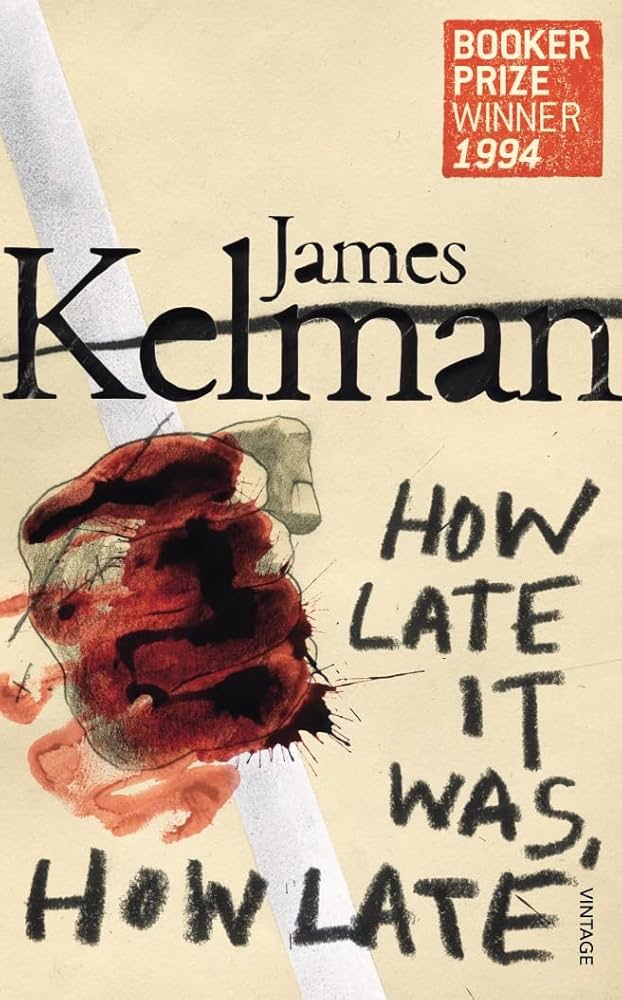

In the final year of my undergraduate degree, I took a course on ‘Postwar Scottish Literature’ in which we were asked to read James Kelman’s How Late It Was, How Late (1994) and found its opening paragraph both beguiling and dizzying:

Ye wake in a corner and stay there hoping yer body will disappear, the thoughts smothering ye; these thoughts; but ye want to remember and face up to things, just something keeps ye from doing it, why can ye no do it; the words filling yer head: then the other words; there’s something wrong; there’s something far far wrong; ye’re no a good man, ye’re just no a good man. Edging back into awareness, of where ye are: here, slumped in this corner, with these thoughts filling ye. And oh christ his back was sore; stiff, and the head pounding. He shivered and hunched up his shoulders, shut his eyes, rubbed into the corners with his fingertips; seeing all kinds of spots and lights.

Reading this again more than a decade later, it’s reassuring how much of what I ended up writing in the book resonates with my reading of the passage now, even though I don’t actually discuss this novel at all. I wrote what was probably a terrible undergraduate essay on the politics of state surveillance and representation, but it wasn’t until I was exposed to narrative theory that I realised what I was puzzling over was pronominal switching. The more I read, the more I wanted to home in on the strangeness of the second-person pronoun in particular – how it seems to address the reader while clearly referring to someone entirely different and fictional.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

Most – if not all – of primary texts I discuss in this book are included precisely because they use you-narration in strange and surprising ways. Why does ‘the (Hot) Priest’ in Fleabag suddenly register some (but not all) of Fleabag’s addresses to the camera? And why does he describe this in such vague terms, like ‘What was that?’ and ‘Where did you just go?’ Why does Carmen Maria Machado include footnotes and a ‘choose your own adventure’ section in her memoir? Why is this memoir that is clearly about herself written in the second person? Why does Alejandro Zambra write Multiple Choice as a sort of ‘comprehension exam’ where so many of the answers are completely the same or otherwise meaningless? These were all strange occurrences I couldn’t make sense of, and writing this book became my way of making sense of them in really surprising ways – like, through twentieth century philosophy!

Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources?

I was incredibly lucky to be able to read the manuscript of Andrew Cowan’s novel Your Fault a couple months ahead of publication, thanks to my PhD supervisor. It was incredibly stimulating on so many levels and the ending was so devastatingly confounding that my supervisor, Mark, said to me at the end of our discussion that it was time to start writing. And he was right because the words practically spilled out of me, which isn’t to say that it was any good. Just that I needed to write and rewrite a million times to be able to make sense of it – and that became the first chapter I wrote! The other text that was difficult to track down was Christine Angot’s Sujet Angot. It was never translated into English and I was only able to find this old, second-hand copy via Amazon – but thank goodness I did!

About the author

Denise Wong is a postdoctoral researcher at Justus Liebig University Giessen, Germany, working on the UKRI project, ‘Reading Post-Postmodernist Fictions of the Digital: Narrative, Cognition, and Technology in the Twenty-First Century’. She is also Reviews Co-Editor of C21: Journal of 21st-century Writings. Her work has been published in Textual Practice, the Journal of Asian American Studies, DIEGESIS and The Problems of Literary Genres. She has contributed chapters to the forthcoming Edinburgh Companion to the Millennial Novel, Narrative Intersubjectivity and Storyworld Possible Selves and The Routledge Companion to Literature and Cognitive Studies.