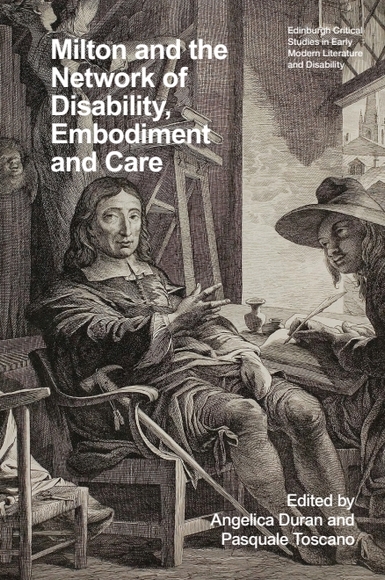

by Angelica Duran and Pasquale Toscano

Milton and the Network of Disability, Embodiment and Care situates the works, legend and reception of the Renaissance poet and politician John Milton within the network of disability, embodiment and care studies.

1) Milton wrote his most famous poem, Paradise Lost, while blind

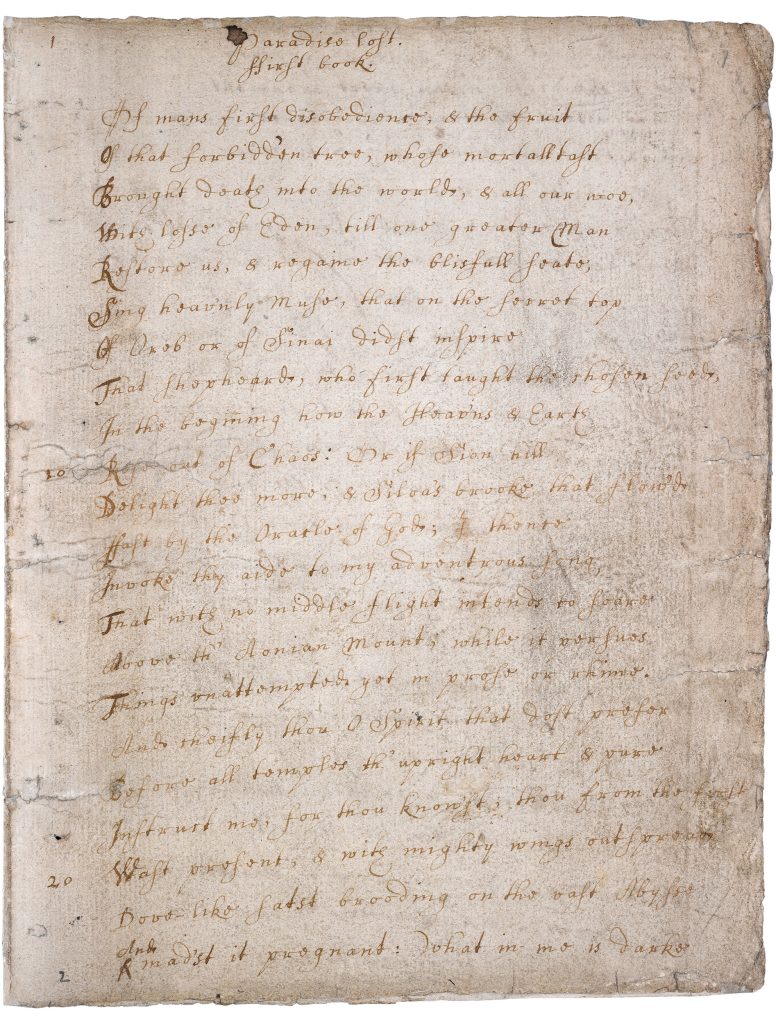

We know a surprising amount about how and when Milton gained blindness, mostly thanks to his letter to the Greek diplomat Leonard Philaras; Sarah Knight’s new Latin-to-English translation is included in our volume. In 1644, Milton began losing his vision one eye at a time, first the left, then the right. By 1652, he was fully blind, well before earnestly setting to work on his epic, Paradise Lost (1667). Certain critics—like the 18th-century philologist Richard Bentley—have doubted that all the words in this richly allusive poem, of nearly 11,000 lines, could be Milton’s own. They’re wrong. Of course he had help—more on that in a moment—but Milton’s early biographers explain that the literary secretaries at hand faithfully took dictation and standardized the spelling and punctuation according to his preferences. All of this was based on complicated protocols Milton worked out—as Thomas N. Corns explains in our volume.

2) Milton anticipates disability pride

While Milton did not use contemporary terms like ableism or crip pride,he anticipates their meanings, often while rejecting the vitriol of his political opponents. (There was no shortage of these, who pilloried his support for radical political causes.) In the Second Defense (1654), Milton responds to one detractor who compared him to the cyclops Polyphemus, violently blinded by Odysseus in the Odyssey, the ancient epic by Homer, who is often portrayed as a blind person. Milton celebrates the many blind “worthies who were as distinguished for wisdom in the cabinet, as for valour in the field.” What’s more, he emphasizes that anyone can become blind, at any time, for natural reasons, with less than tragic outcomes. With a nod to St. Paul, Milton even declares, “in the proportion as I am weak, I shall be invincibly strong; and in proportion as I am blind, I shall more clearly see.” Other famed authors often depicted with disabilities they acquired in the battlefield are Luís Vaz de Camões, the Portuguese author of the epic The Lusiads (1572), and Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, the Spanish author of the novel Don Quixote (1605, 1615).

3) Milton had disabled role models

Disability scholars have emphasized the importance of crip ancestry and kinship—lineages of disabled elders for community and support. Even without this vocabulary, Milton constructed something similar for himself. In his treatise against pre-publication censorship, Areopagitica (1644), Milton claims to have met Galileo Galilei (1564–1642)—one of Renaissance Europe’s most famous blind persons—who had “grown old, a prisoner to the Inquisition, for thinking in Astronomy otherwise then the Franciscan and Dominican licencers thought.” This emblem of looking to worlds beyond our ken clearly stayed with Milton, too: Galileo is the only one of his contemporaries explicitly referenced in Paradise Lost. In another passage often read as autobiographical, the epic narrator cites the challenge of blindness, “eyes, that rowle in vain / To find their piercing ray,” only to insist that the challenge does not diminish the ability to “see and tell / Of things invisible to mortal sight.” Milton also cites four precedents, blind poet-seers from ancient Greco-Roman culture: “Blind Thamyris and blind Maeonides [that is, Homer], / And Tiresias and Phineus Prophets old.”

4) Milton advocated for what we now call accommodations

In early modern England, legal protections for physically or mentally disabled people were scarce. All the same, Milton was granted a series of assistants (like the poet Andrew Marvell) for his work as a high-level civil servant during the 1650s. After returning to private life, Milton likewise assembled an active care network of support. Tradition has it that his recalcitrant daughters bore the brunt of this work—and to be sure, they were conscripted to help. But many men stepped up as well, including the Quaker Thomas Ellwood, who wrote fondly of Milton in his autobiography—and who is depicted on our volume’s cover, reproduced at the top of this webpage. Ellwood suggests that scribes and readers did not approach their work as tiresome caretaking for a feeble invalid. Instead, they viewed it as a dynamic experience of mutual respect and engagement with someone who both received care and offered it, through lessons and advice.

5) Milton has, himself, served as a crip ancestor, including for multiply marginalized writers

Here are but a few examples—some from our volume’s introductory chapter. In the first slave narrative (1789), Olaudah Equiano frequently block quotes Paradise Lost to condemn white enslavers who mutilated the Black people in their grasp. In another autobiographical text (1965), Malcolm X, grappling with his dyslexia in prison, imagines Milton’s Satan as an avatar for logics of oppression. The first blind person recorded to have earned a Ph. D. in the U. S.—Eleanor Gertrude Brown (1887–1964)—wrote a dissertation at Columbia University that reinterprets Milton’s references to blindness, making some use of her own experiences. Author and activist Helen Keller (1880–1968)—deaf and blind from the age of 2—founded the John Milton Society for the Blind to make costly Braille books more available worldwide. And in the twenty-first century, Monica Youn vamps on the line-ending rhymes of Milton’s Sonnet 19 (“On His Blindness”) to share her own experience of infertility. Milton also abides in disability narratives of our own!

About the editors

Angelica Duranis Professor of English, Comparative Literature and Religious Studies at Purdue University, where she has also served as Purdue’s Director of Religious Studies (2009–2013), Interim Director of Creative Writing (2022–24) and affiliate faculty of Critical Disability Studies. She is the author, editor and co-editor of ten books, including Milton among Spaniards (2020), Global Milton and Visual Art (2021) and Milton Across Borders and Media (2023). She has served on the Executive Committee (2012–21) of the Milton Society of America, on the editorial board of Milton Quarterly (2005–) and as Conference Chair of the Renaissance Society of America (2022–27).

Pasquale Toscano is Assistant Professor of English at Vassar College, after earning a master’s degree in Classics from the University of Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar and a PhD in English from Princeton University. He is a co-winner of the Sixteenth Century Society’s Harold J. Grimm Prize for scholarship on the Reformation and was named a 2023–24 Peter Ogden Jacobus Fellow, Princeton’s highest honour for graduate students. His scholarship appears in Studies in English Literature, 1550–1900 (SEL), Classical Receptions Journal, Disability Studies Quarterly, The Oxford Handbook of George Herbert and Shakespeare and Early Modern Madness. His public-facing and creative writing focus primarily on disability-related issues and appear in The New York Times, The Atlantic and other venues.