By Annelies Van Assche

Annelies Van Assche is the author of (Un)Teaching the Canon: An Approach to Teaching Dance History in Western Europe in issue 43.2 of Dance Research.

Bye bye canon is easier said than done. Especially when teaching art history in the heart of Europe. There is definitely an unsettling silence in Western Europe on this topic, stemming from the tension inherent in our geographical and historical position. How, then, do dance history lecturers in Europe navigate the challenge of addressing the dance canon without reinforcing Eurocentric narratives? Here are five ways to (un)teach the canon in dance history:

1. Dialoguing Materials

Unteaching starts by unlearning habits of passive consumption. As a preparatory assignment for my classes, I pair canonical materials with critical readings and ask students to reflect on the provided dialogical material. For example, to prepare a class on German expressive dance from the early 20th century including controversial but highly influential pioneers such as Mary Wigman, students must engage with Fabián Barba’s re-enactment in A Mary Wigman Dance Evening (2009) and read Barba’s own writing based on the research and aftermath of the piece. The pairing invites students to recognize that dance history is not a linear progression but a field of negotiation across cultures, politics and memories. This method reframes canonical works as sites of discussion rather than authority.

2. Dancing Back to the Canon

In class, guiding students through different performance analysis lenses allows students to perceive how aesthetic resistance operates through embodiment, humor and hybridity. It expands their capacity to read dance as a political archive, one that speaks back to Europe from its margins. In my teaching, I borrow the postcolonial notion of ‘writing back’ from postcolonial literature scholars Ashcroft, Griffiths and Tiffin (1989) as one such lens and apply it choreographically as ‘dancing back‘. Artists with an immigrant or diaspora background in Europe, like Moya Michael, perform precisely this act as they dance back to Western dance languages to reclaim space for ancestral and diasporic embodied knowledge. In Michael’s Coloured Swan I: Khoiswan (2018), she recognizes classical ballet imagery, like fifth position, in Khoi cave drawings and reclaims movement vocabularies historically used to fetishize Black women by evoking Saartjie Baartman through image and poetry. This ‘dancing back’ does not destroy the canon, but it forces it to see its own colonial mirror.

3. Muddying the Canon

Another lens in performance analysis highlights how the canon is often stripped of its purity and made into something messy, thereby mostly confusing the audience with a new dance language unfamiliar to them. In class, we explore Jean-Philippe Rameau’s exoticing ballet-opera Les Indes Galantes (1735), yet its 2019 version restaged by director Clément Cogitore and choreographer Bintou Dembélé, at the Paris Opera. The production replaced Baroque ballet’s idealized images of ‘exotic natives’ with hip-hop dancers, staging a radical collision between street culture and opera elitism. Drawing on Juan Vallejos’s concept of ‘embarrar el canon‘—to ‘muddy’ the canon—students and I discuss how Dembélé’s choreography disrupts the aesthetic purity of European dance. Her krumpers literally take over the Bastille by storm, muddying distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low,’ ‘white’ and ‘Black,’ ‘art’ and ‘politics’. This example resonates too with Akram Khan’s reimagining of Giselle (2016), where the Romantic ballet is restaged through the updated lens of migrant labor and a (con)fusion of Kathak and ballet. Both works reveal that unteaching does not mean rejecting heritage entirely.

4. Dancing With and Against the Canon

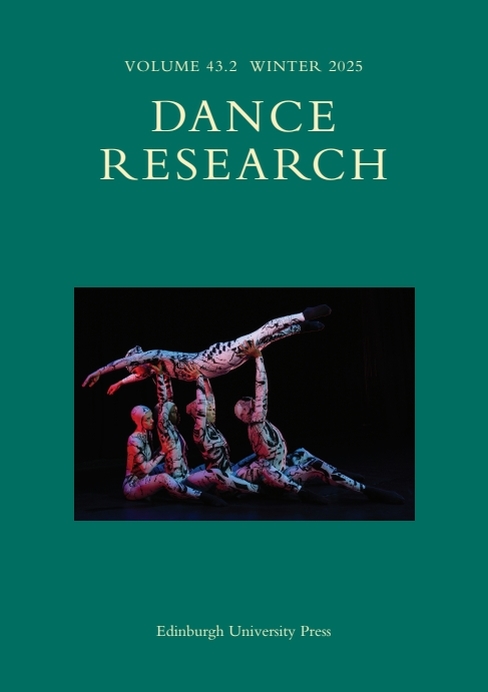

Regional canons can be just as exclusionary as global ones. In Belgium, where I live and teach, the ‘Flemish Dance Wave’ of the 1980s, which includes the now internationally renowned choreographers Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Wim Vandekeybus and Alain Platel, forms a local canon celebrated for innovation. Enter Flemish Primitives (2022) by Chokri Ben Chikha, a witty and subversive stage piece that parodies the myth of Flemish artistic genius. Six dancers with migrant backgrounds reenact iconic moments from the Flemish Wave as part of a talent show. By turning these moments into auditions, the work exposes how race, labor and identity are commodified in the dance world. The canonic figures are embraced for their exceptional contributions in terms of movement innovations but highly critized for their (labor) ethics. In class, this performance helps students see that canons are not just aesthetic but also economic and institutional. This lens allows students to realize that critique and continuity coexist as they learn to both appreciate and dismantle what they inherit.

5. Exhibiting Local Histories

Inspired by Rafael Guarato’s idea of ‘abandonment’ in historiography, I assign students to explore what has been left out of local historiography. Each year, they research and curate exhibitions on overlooked Belgian dance figures and bring these hidden histories to light, for example focusing on the often neglected history of dance in Belgium’s Francophone context. This practice also redefines archives as living spaces where memory, politics, and embodiment intersect. By focusing on what was ‘abandoned’, students challenge Eurocentric as well as Flemish-centric narratives and recover the complexity of local identities.

About the author

Annelies Van Assche obtained a joint doctoral degree in Art Studies and Social Sciences in 2018 for studying the working conditions of European contemporary dance artists. She is a senior postdoctoral researcher at the department of Art History, Musicology and Theatre Studies of Ghent University and lecturer at the Royal Conservatoire Antwerp’s dance department (Belgium). Her research focuses on the relation between labor and aesthetics in contemporary dance. She is author of Labor and Aesthetics in European Contemporary Dance. Dancing Precarity (2020) and co-editor of (Post)Socialist Dance. A Search for Hidden Legacies (Bloomsbury, 2024). She is a member of research group S:PAM, CoDa – European Research Network for Dance Studies, and the Young Academy of Flanders.

Featured image: Flemish Primitives by Chokri Ben Chikha, Laura Neyskens and Action Zoo Humain (2022) (Photography: Kurt Van der Elst).