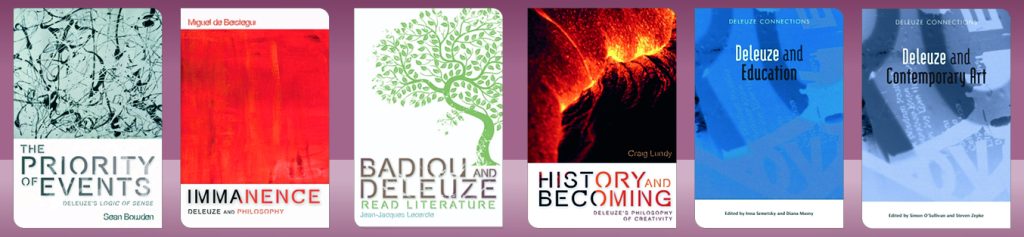

2025 marks the centenary of the birth of Gilles Deleuze. Throughout the year, we have explored the impact of this towering figure in twentieth-century philosophy.

To wrap up our celebrations, we have two final blogs from leading Deleuze scholars. This month, Rosi Braidotti explores how Deleuze’s ideas foster a non-traditional, nomadic approach to philosophy that emphasises empowerment, multiplicity and a feminist perspective.

Find out more about our centenary celebrations.

By Rosi Braidotti

The author of the Anti-Oedipus leaves his readers in the place of knotted subjects: grief alternates with gratitude, and yet we must avoid the very oedipal position of philosophical orphans. Will his scattered heirs manage to combine the urge to mourn his loss with the imperative to respect the conceptual attack Deleuze launched against the paternal (phallic) metaphor and the ideals of order (at both the macro and micro levels) it conveys? As a feminist deleuzian, that is to say as an anti-Oedipal and therefore undutiful daughter I think that the loyalty that is due to a philosopher of his calibre must not be translated back into the terms of a masculine theoretical genealogy – albeit a radical one – that he spent his life re-figuring. Today I want to pay homage to this – the subversive – aspect of Deleuze’s thought, much as I would like to celebrate his modesty, the frugal simplicity of his lifestyle that was so removed from the glamour and the mondanités of Parisian philosophers. It is well-known that, in contrast with the necrophilic style of the nouveaux philosophes, Deleuze never bothered to cry over the death of philosophy, but the reason for this was the opposite of blind faith in tradition. It is rather that Deleuze was committed to thinking through the radical immanence of the subject after the decline of metaphysics and of its phallo-logocentric premises. Let me suggest therefore that the appropriate way of mourning Deleuze may be the joyful affirmation of positive and multiple differences – even and especially among his followers – and of loving irreverence – even towards his own thought – as a form of empowerment of new ideas.

I still find it hard to believe how much Deleuze did love philosophy. Having settled into a state of structural ambiguity towards this discipline, I have a lot to learn from the dedication Deleuze displayed towards the activity of creative thinking. Deleuze’s work is marked by the positivity of thinking as a process of becoming, which transcends the boundaries of critical thought and projects us forcefully through to more adequate forms of representation of subjectivity. With respect to such theoretical creativity, I think Deleuze’s philosophy is one of the few that manage to emerge from the ruins of metaphysics with a strong counter-proposal. Even more than his frère-ennemi Michel Foucault, Deleuze has marked contemporary philosophy through his radical redefinition of the human subject, in terms that are never just socio-political or aesthetic, but that rather seek for interconnections between them. Deleuze signifies, for me, the full deployment of the philosophy of multiple becomings, which is much more than the critique of the metaphysical foundations of identity: it is also a vote of confidence in philosophy’ a capacity for self-renewal. An essential element of the vitality of philosophical discourse is the wilful shedding of disciplinary grandeur, in favour of dialogical exchanges with other disciplines – especially physics and mathematics – but also with contemporary discursive fields, such as cinema, modern art and technological culture. Philosophy thus renews itself by becoming an enlarged notion: it is the activity that consists in reinventing the very image of thinking human subjectivity, so as to empower the active, positive forces of thought and disengage the reactive or negative passions.

Throughout the many phases that characterize his work, Deleuze never ceased to emphasize the empowering force of affirmative passions. In his quarrel with the canonized version of the history of philosophy (dominated by the holy trinity of Hegel, Husserl and Heidegger), he emphasized instead a counter-genealogy of materially enfleshed philosophy (the empiricists, Spinoza, Leibnitz and Nietzsche), which I continue to find breath-taking, in the extreme intelligence of its simplicity.

Like many travel companions on the nomadic journey through Deleuze’s philosophy, I regret that his fame is linked, at least for English-speakers, to L’Anti-Oedipe and to his alliance with the “schizo-analyste” Felix Guattari and the anti-psychiatry movement. Not because I underestimate the importance of their quarrel against the dogmatism and the political conservatism of Jacques Lacan’s revisitation of Freudian psychoanalysis. On the contrary, I find this phase very relevant in that it highlights Deleuze’s notion of the positivity of desire, which he opposes to the Hegelian legacy in the Lacanian dialectics of lack. I do think, however, that this particular segment of Deleuze’s work should be read as a set of discontinuous variations on his philosophy of radical immanence and positivity. One should not isolate, for instance, the figuration of the desiring machines from this general framework.

In speaking of positive forces or passions, Deleuze accomplishes a double aim: on the one hand he revalorizes affectivity in his theory of the subject and on the other he gives ample space to the body and the specific temporality of the embodied – or rather the enfleshed – human. In so doing, he redefines the body in a non-essentialistic manner, deconstructing non only the humanistic myth of an authentic human nature but also the way in which psychoanalysis ‘sacralized’ the sexual body. Deleuze wants to replace both these views with a high-tech brand of embodied vitalism that was to engender the ‘intensive’ style of writing that became his trademark. The result is the quest for alternative figurations of human subjectivity and of its political and aesthetic potential. Rhizomes, bodies without organs, nomads, becoming-woman, flows, intensities and multiple becomings are part of this rainbow of alternative figurations Deleuze threw our way.

Deleuze confronted the question of the feminine or the becoming-woman of philosophy with integrity, inscribing it at the very heart of his conceptual thought. Nontheless, there is an unresolved knot in Deleuze’s relation to the feminine. It has to do with a double pull that Deleuze never solved, between on the one hand empowering a generalized ‘becoming-woman’ as the pre-requisite for all other becomings and, on the other hand, emphasizing the generative powers of complex and multiple states of transition between the metaphysical anchoring points that are the masculine and feminine. I will express it as a question: what is the relation between feminist theories of sexual difference and Deleuze’s philosophy of difference? Deleuze’s work displays on the one hand a great empathy with the feminist assumption that sexual difference is the primary axis of differentiation and therefore must be given priority, if we are to redefine the transcendental plane of the subject. On the other hand there is also a tendency, prompted by Guattari, to dilute metaphysical difference into a multiple and undifferenciated becoming. Questioned and probed by women philosophers on this issue, not unlike Freud, Deleuze deferred to the superior knowledge of women on this matter.

I do think, however, that, even unresolved, the notion of the ‘becoming-woman’ of philosophy functions as one of the propellers of Deleuze’s philosophy. Conveyed by figurations such as the non-Oedipal little girl, or the more affirmative Ariadne, the feminine face of philosophy is one of the sources for that transmutation of values away from reactivity and into positivity, which allows Deleuze to overcome the boundary that separates mere critique from active empowerment.

Last but not least, Deleuze’s emphasis on the ‘becoming woman’ marks a new kind of philosophical sensibility which has learned how to undo the straight-jacket of phallocentrism to open up towards otherness. In Deleuze’s thought ‘the other’ is not the emblematic mark of alterity, as in classical philosophy; nor is it a fetishized and necessary other, as in deconstruction. The other for Deleuze is rather a moving horizon of perpetual becoming, towards which the split and nomadic subject of postmodernity moves. I would like to remember Deleuze as “le philosophe aux semelles de vent” (the philosopher with shoe-soles made of wind), flying across the desolate space-time continuum of our era, searching for that window that would open out to the other side of gloom and nihilism.

Un jour notre siècle sera deleuzien.

About the author

Rosi Braidotti is a philosopher, feminist, nomadic writer, and posthuman thinker. She holds Italian and Australian citizenship and lives in the Netherlands. As a postgraduate student in the late 1970’s, she followed Deleuze’s classes at the university of Vincennes in Paris. She is currently Distinguished University Professor Emerita at Utrecht University and Honorary Professor at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. She received the Humboldt Research Award in 2022 for her life-long contribution to scholarship in the Humanities. She is an Honorary Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities and a Member of the Academia Europaea. She holds Honorary Degrees from Helsinki (2007) and Linköping (2013). Key publications a trilogy on nomadic thought (Nomadic Subjects, 1994 and 2011; Metamorphosis, 2002 and Transpositions, 2006); and a trilogy on the Posthuman (2013, 2019, 2022).

Website: www.rosibraidotti.com

Instagram: @rosibraidottiofficial

Find out more about our Deleuze centenary celebrations

Credits: Republished with permission from Radical Philosophy, vol. 76, March/April 1996, pp. 3-5.