Interview with Daniel Dufournaud

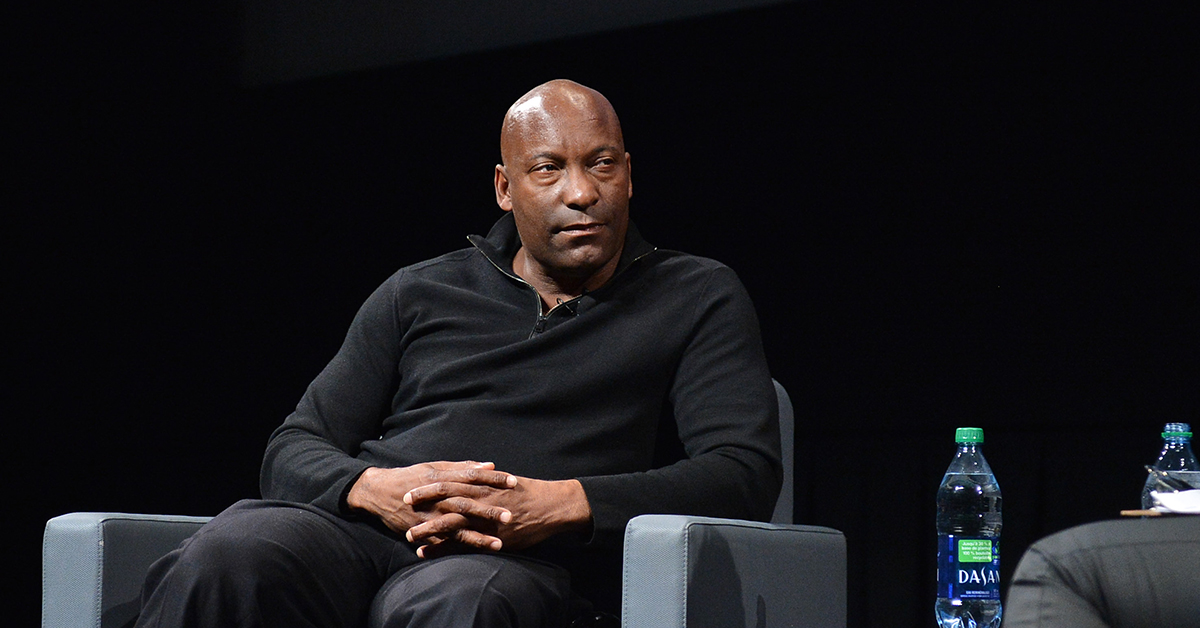

Critically re-evaluates the work of John Singleton, a celebrated Black American auteur whose work helped break a glass ceiling in Hollywood

What inspired you to put together this collection of essays on John Singleton at this particular moment in time?

The idea for this collection originated from two places. The first was my academic training in American literature and film. My forthcoming book examines how contemporary American literature responds to the social and economic conditions of neoliberalism. I was naturally interested in American film’s response to these same conditions. Singleton burst onto the scene at a time when neoliberal policy work was beginning to unite US politicians across partisan lines, and so I’ve always thought that his films have a great deal to tell us about contemporary America.

The second was fandom. I was sad when Singleton passed away so young. As a fan, you can only dimly imagine what that loss felt like for his friends and family. However, in the wake of his passing, it didn’t feel like enough casual movie fans and cinephiles adequately registered the enormity of his contribution to American cinema. I had hoped that Singleton would return to form and direct something qualitatively similar to Boyz N the Hood, Baby Boy and Higher Learning. These are all flawed films, but they continue to interest me, continue to sound timely notes in a period of right-wing revanchism that does not feel that different from the 1990s and early 2000s.

What are some of the lesser-known or underappreciated works of Singleton’s on which the book shines a light?

I’m pleased to share that the collection features two chapters that focus on Higher Learning and Rosewood, respectively. A campus film that received a great deal of attention upon its 1995 release, Higher Learning has a higher profile than Rosewood. But it’s still criminally underappreciated. In their chapter on the film, Khirsten L. Scott and Ariana Denise Brazier deftly show how it continues to resonate thirty years after its release. They contend that the film highlights how the rhetoric of multiculturalism fails to address systemic sources of alienation among students of color.

Rosewood is perhaps the most overlooked of Singleton’s great films. It recounts a grim, sobering moment in American history: the 1923 Rosewood massacre. In the introductory chapter of the collection, I speculate that the film’s tepid reception was partly due to the glut of big-budget historical films released in the late 90s, films that tend to sanitize the past rather than show it for what it was. In their chapter on the film, Ed Cameron and Linda Belau combine psychoanalytic and deconstructive methodologies to contend that the film performs a reparative function while challenging dominant ideas of progress.

Singleton was often praised—and sometimes criticized—for how he represented Black masculinity. How does your collection address this topic?

There is no circumventing Singleton’s masculinism. Beyond the films themselves, some of the comments he made in interviews suggest a single-minded focus, not only on Black masculinity, but on a narrowly conceived idea of that subject position. Consequently, almost every chapter in this collection addresses, to some extent, his preoccupation with Black masculinity and his relative inattention to, or limited understanding of, female experience.

In particular, the opening section of the collection features two chapters that unpack this aspect of his work and its political implications. In the first chapter, Indya J. Jackson scrutinizes the problematic gender politics running through Boyz N the Hood and Baby Boy; she contends that Singleton’s rejection of racial essentialism is sometimes outweighed by his tacit affirmation of the worst stereotypes foisted upon Black mothers and matriarchal domesticity in neoliberal America. In the following chapter, Angela Tharpe echoes this argument, but she sees in Singleton’s heroic father figures an element of hopeful fantasy that she traces back to his interest in comics.

What do you hope readers—scholars, students or film fans—will take away from this collection about Singleton’s influence and artistic legacy?

Although I am biased, this collection paints a picture of a filmmaker who was principally two things: generative and oppositional. He was generative because, without the massive, surprising success of Boyz N the Hood, it is unlikely that Hollywood studios would have greenlit the spate of films made by and about Black Americans in the 90s. Moreover, long before Hollywood began to sincerely address issues of diversity, Singleton labored behind the scenes to make his sets more diverse, and he worked hard to get his friends’ projects over the finish line.

More importantly, Singleton made politically charged films unconstrained by fear of alienating certain movie fans and of fueling debate. In literary studies, where I spend most of my time as an academic, there is now a lot of discourse encouraging scholars to rethink their impulse to critique. The political right in the US is led by politicians whose contemptible agendas are matched only by their sensitivity. Singleton’s unwavering oppositionality and his commitment to truth telling and critique are just as important today as they were in the 90s and early aughts.

About the editor

Daniel Dufournaud is an Assistant Professor at the University of Macau. His work appears in such journals as Poetics Today, College Literature, Studies in the Novel, Journal of Modern Literature and Journal of American Studies.