By Alasdair Raffe

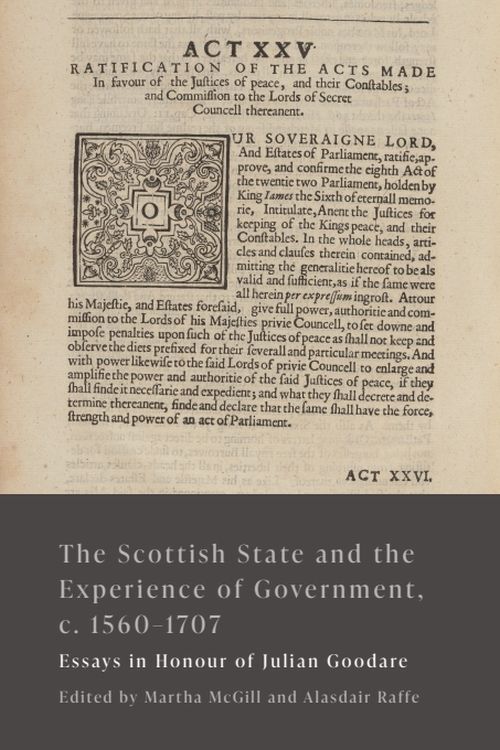

Alasdair Raffe is co-editor of The Scottish State and the Experience of Government, c. 1560-1707, a new book on government and its impacts on the Scottish people.

What did the Scottish state do in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Scotland? How powerful was the monarch? In what ways did people understand the country’s constitution and the powers of its parliament? And how did ordinary Scots experience government? What were the benefits and adverse consequences of their interactions with the state’s institutions?

The Scottish State and the Experience of Government, c. 1560-1707 seeks to answer these questions. Inspired by the work of Julian Goodare, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Edinburgh, a team of historians offers new perspectives on Scottish government from the Reformation in 1560 to the union with England in 1707.

Changing Government

The late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were a time of governmental change in Scotland. King James VI raised increasing sums in taxation, spending some of the proceeds on a growing royal bureaucracy. New officials were created, courts and commissions established. The country’s noblemen gradually ceased to resolve their disputes through violence; many became more dependent on government office and pensions. For all the signs of innovation, however, historians have been unable to agree about the significance of James’s reforms. Did they amount to a ‘revolution’ that decisively centralised and expanded state power, or were they minor developments, especially when compared to changes in other European countries?

Historians have extensively discussed the Scottish state under James VI, but there has been less attention to governmental change after the king’s death in 1625. As well as reviewing the debate about Jacobean government, The Scottish State and the Experience of Government, c. 1560-1707 explores hitherto neglected episodes in state formation from the 1570s to the early eighteenth century.

Following the overthrow of Mary Queen of Scots in 1567, civil war broke out between the queen’s allies and supporters of the regime created in the name of her infant son, James VI. Each side in the civil war asserted its legitimacy by acting like a state. At the end of the sixteenth century, when James’s rule was secure, he enhanced the authority of his privy council. The council assumed responsibility for daily government after the king relocated to England as James I in 1603. Other developments in state power concerned the constitution and influence of parliament. During their revolution against King Charles I, the Covenanters remodelled parliament, removing the bishops who had formerly supported royal policies. By the later years of the century, the Scottish state had a standing army. The book analyses the army’s expansion during the reign of Charles II and the controversies generated by greater state power under William II and Anne. We also consider the state’s responses to the particular challenges posed by the highlands and islands.

The Experience of Government

Julian Goodare’s research has often investigated the impacts of state power on the Scottish people. He is well known for his writings and media appearances on the witch-hunt. But the state’s institutions and officials did not only punish crimes – real and imaginary – but also provided services to the population. When planning the book, we tried to balance studies of the state’s coercive force with chapters portraying more positive experiences of early modern government.

Many Scots chose to use the courts to remedy disputes with their neighbours. By studying debt litigation, for example, we perceive not only the networks of credit that knitted together early modern communities, but also the potential for the state’s authority to serve the interests of its subjects. Likewise, Scots readily sued each other for slander; the courts usually facilitated a peaceful resolution of neighbourly tensions.

Nevertheless, we have plentiful evidence of the state’s power to control and punish. In each part of the country, a nexus of local courts imposed social discipline on the population. The central government in Edinburgh employed instruments of punishment and torture, some of which are now preserved in the National Museum of Scotland. The early modern period saw a long series of witch-hunts. The Scottish State and the Experience of Government, c. 1560-1707 examines the little-known prosecution of witches in Queensferry in 1643-4, and the famous North Berwick witch-hunt of the 1590s – which is reinterpreted as the ‘great Tranent witch-hunt’. In the case of Major Thomas Weir and his sister Jean, who were convicted of bestiality and incest in 1670, we witness not only the state’s punitive power, but a battle to interpret their crimes and control their reputations.

It is common for a festschrift to be kept secret from its honouree until publication. Departing from this tradition, we invited Julian Goodare to contribute to the book. His chapter, ‘State Power Revisited’, is both a summation of the theoretical issues involved in understanding early modern government and a stimulus to further exploration. By opening debates about Scottish state formation after 1625 and the people’s experience of government, we hope that the book encourages new research in this important area of Scottish history.

About the Author

Alasdair Raffe is a Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Edinburgh. He has published widely on religion, politics and ideas in early modern Scotland. He is the author of Scotland in Revolution, 1685-1690 (Edinburgh University Press, 2018).

Explore related articles on the EUP Blog

A parcel of rogues in a nation? Twenty-five years of the Scottish Parliament

Juteopolis?: Dundee’s history as a leading textile town

Image Credits

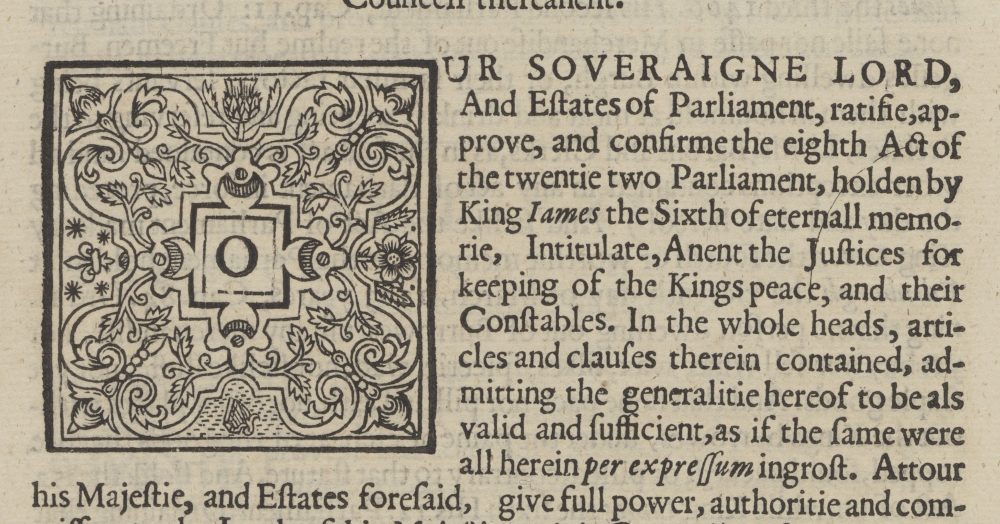

- Featured image: The Acts made in the First Parliament of our most High and Dread Soveraigne Charles, by the Grace of God, King of Great Britaine, France, and Ireland (Edinburgh, 1633), p. 58, NLS, Ry.II.b.21(6). Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC-BY) licence with the permission of the National Library of Scotland. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- Parliament House, by James Gordon of Rothiemay (1615-86). Source: https://scotparlhistory.stir.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Parliament-House-PDF.pdf ↩︎

- The Maiden, in the Monarchy and Power gallery, National Museums Scotland, H.MR.1.

Image © National Museums Scotland ↩︎