by Antonia Wimbush

BUMIDOM (1963–1982) and its Afterlives examines the literary and cultural legacy of the BUMIDOM in France and the French Caribbean

My new book, BUMIDOM (1963-1982) and its Afterlives, argues that books, films, TV shows, and music are not only enjoyable forms of escapism. They can play a memorial function for communities whose collective memory has been marginalised, overlooked, or silenced. For groups whose past is not represented in museums, memorials, history textbooks, or school curricula, it is through creative works that they are able to remember their traumatic past.

Writers, film makers, and artists thus become memory activists, bringing silenced memories of forgotten groups into the dominant collective memory.

The BUMIDOM

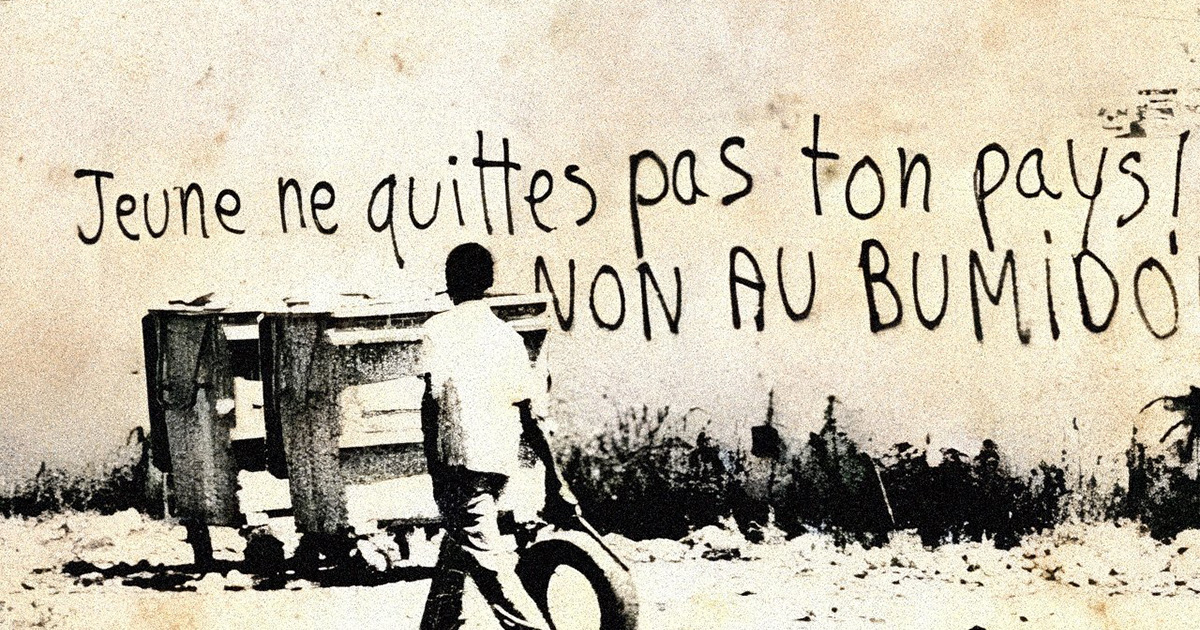

The book examines the specific case of the BUMIDOM (Bureau for the Development of Migration in the Overseas Departments), a labour migration agency which was set up by the French government in 1963. The French Caribbean islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe were experiencing economic decline and many people wanted independence from France. Mainland France, meanwhile, was in desperate need of a workforce to rebuild the country during the post-war economic boom. The BUMIDOM was thus created to move young, working-class, and politically active people from the departments to mainland France. The BUMIDOM selected candidates, financed their trip, and found them housing and work in France.

In just under 20 years, 160,000 Martinicans and Guadeloupeans migrated to France through this scheme. For some, migration was a positive experience because it allowed them to enjoy personal and professional success which they would not have had if they had stayed on the islands. For many, however, it was exploitative and coercive. They were subjected to racial discrimination and the jobs they were given in healthcare and domestic service were low-skilled and under-paid.

Outside of Guadeloupe and Martinique, little is known about the BUMIDOM. It is not taught in French schools, it does not feature in history textbooks, and there is little mention of its impacts in national museums in mainland France.

In the book, I argue that the French government has chosen not to commemorate the BUMIDOM to avoid admitting that migration was organised on grounds of race. This would contradict the ideology of universalism on which the French Republic is founded, in which all French citizens are equal, regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, or gender. By being subjected to state-sponsored discrimination, Guadeloupeans and Martinicans – who were, and still are French citizens – were denied their full rights. Their racial origins prevented them from being accepted as French citizens.

Remembering the BUMIDOM Today

In the book I analyse works that were produced when the BUMIDOM was in operation – such as François Ega’s 1978 text of life writing, Lettres à une noire – alongside more contemporary works – including Charlise Curier’s 2019 autobiography, Mon aventure avec le BUMIDOM. This methodology enables me to understand how memories of migration have circulated across borders, families, and generations. I also examine items produced in different genre and media to give a diverse depiction of migration through the BUMIDOM.

What I found was that most texts, films, and songs are critical of the BUMIDOM. They emphasise the mismatch between the expectations of BUMIDOM participants and the reality of the life they encountered in cold, grey, and unwelcoming France. Some of the cultural works are educational. For example, the graphic novel Peyi an nou (2017) by Jessica Oublié and Marie-Ange Rousseau offers factual detail about what it was like to migrate to France in the 1960s and 70s. It also reveals what it was like for the authors to carry out archival research and interviews on a topic which is still considered taboo by many Guadeloupeans and Martinicans today.

Given that 2023 marked the sixtieth anniversary of the creation of the BUMIDOM, there has been an increase in commemorative activities on both sides of the Atlantic as communities have come together to remember their migratory past. For example, in March 2023, the Caribbean association Sonjé held a two-day event in the Parisian suburb of St-Denis which involved film screenings and round tables. From March to June 2025, an exhibition about the history of the BUMIDOM is being held at the Departmental Archives in Guadeloupe. These memorial events are the fruits of individual activists, community organisations, and research networks, rather than national, state-sponsored events. While there is still a long way to go before memories of migration through the BUMIDOM are fully respected and preserved by the French state, these events, books, and films help to keep the memories of this important historical event alive.

About the author

Antonia Wimbush is Lecturer in French Studies at the University of Melbourne. Her previous publications include Autofiction: A Female Francophone Aesthetic of Exile (2021) and Queer(y)ing Bodily Norms in Francophone Culture (2021), co-edited with Polly Galis and Maria Tomlinson.