by Peter Robson

Peter Robson is the editor of The Fight for Rent Control, an important socio-legal study of the Glasgow Rent Strikes of 1915 and the introduction of urban rent control.

In 1915, the world was dominated by authoritarian dictators and the war in Europe. Markets were in turmoil. Rents were out of control and tenants faced eviction at the whim of their landlords. Fast forward to 2025 and the world is, once again, dominated by authoritarian dictators, with markets in turmoil, out of control rents and tenants facing eviction at the whim of their landlords.

In the intervening century (along with the struggle for democracy for all), welfare provision replaced charity, tenants won the right to not be evicted and to have their rents controlled. There has been a struggle by tenants in the past century between the drive for social and political progress and the forces of reaction. How these forces have fared has been one of ebb and flow. At present, prospects for tenants do not look very positive with the shift towards the simplistic populist politics that became fashionable in the 1930s. As ever, simple solutions are offered but are unlikely to work within the confines of democratic society.

Why are there no large scale demonstrations today, nor a movement today to protect tenants from the vagaries of the market? The key is to understand the major differences between now and then. For a start, the impact of the war in Europe has yet to make a major impact on people’s lives in Britain. Of course, this may change. The number of tenants is also significantly different. In 1915, 90% of residential property in Britain was privately rented. Nowadays, it is only 19%. In addition, the trade union movement and its political representative are a good deal weaker than they were during the First World War.

However, change is not impossible. It’s worth considering what factors enabled a ragbag of women to effect a major change in housing policy which resonates today.

Motivations for resistance

When war broke out in 1915, one of the more unappealing aspects of the private profit system was the way the market operated in housing. Demand for property near munitions rose and rents were increased. While men were away fighting for their country, landlords were evicting those left behind to take advantage of this situation. Across the country resistance started. It found its most extensive expression in the west of Scotland. The Fight for Rent Control traces exactly why the Glasgow area was such a fertile ground for effective direct action. The resistance to eviction and demands for rent control can be found in the backgrounds of the tenants in the Irish and Highland rent wars.

Landlords have always had a doubtful reputation among the wider public. They have in many instances, especially in Ireland and Scotland, earned this opprobrium. This is part of the folk history in songs, paintings and stories passed down to those who left the countryside to work in the towns and cities of the west of Scotland.

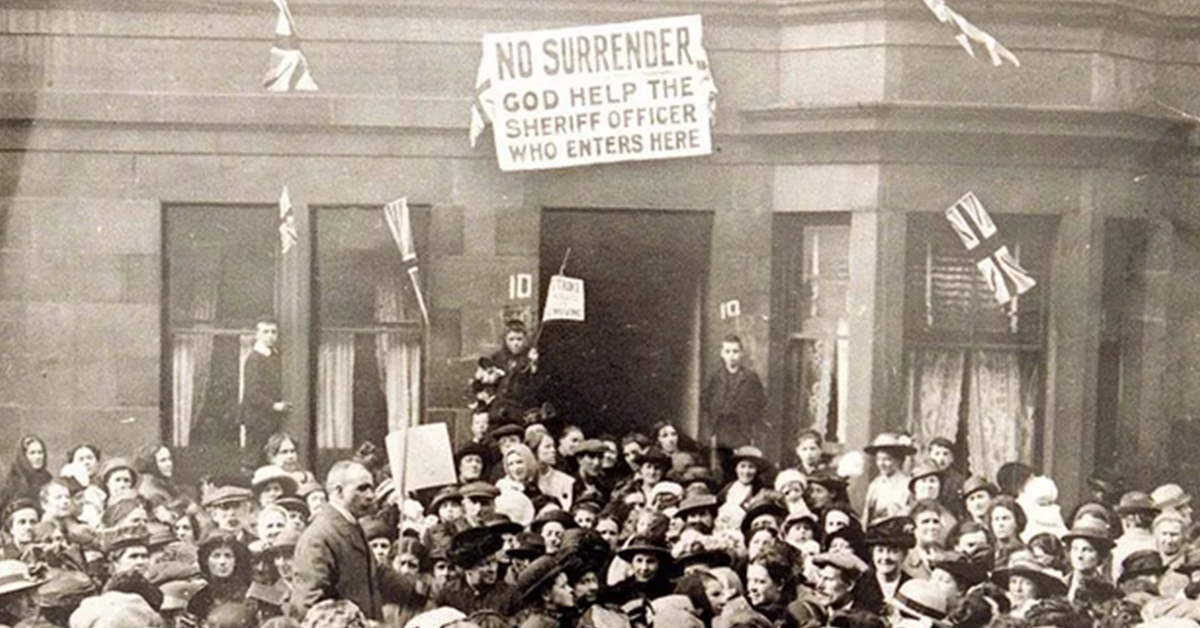

The rent strikes of 1915 in Glasgow were fed by long-standing resentment towards landlords from those whose roots stemmed from the forced emigration of tenants from the Highlands and Ireland. This has extensive expression in many forms of culture keeping this history alive. This outlook was made worse by the material conditions encountered by working class residents of Glasgow. It is this combination which provided such fertile ground for serious and effective action, led by well-organised networks of groups throughout the city. A clear timeline of organisations and events which led to the government of Asquith’s introduction of rent controls and security in December 1915 can be seen here.

The power of working class action

It is helpful to look at the direct actions of the women leading the rent strikes. What happened here was resistance to attempts to evict. The ability to evict at will still remains with landlords. Whether government policy can change in the current times is unknown. The levers the tenants had in 1915 are different. This was at a time with no radio, no television, no internet and precious few phones. What they had were communities which were close-knit and with common problems.

When we see how the 1915 government made concessions with demonstrations at the courts and strikes, it offers a model of sorts. The combined street activism and workplace militancy built to a stage where the government felt it had no other option but to provide an across-the-board policy on the rent question. Any modern fight for rent control and against arbitrary rent increases is likely to have to go through parliament. In 1915, with rent rises and evictions taking place elsewhere, Glasgow illustrated the potential of combining working class action and labour militancy. Modern technology provides unexpected opportunities with the possibility of extensive instant communication between individuals and groups operating any kind of resistance to the status quo. However, just like in 1915, any perceived threat to the principles of free market economics is likely to be seriously resisted.

About the author

Paul Watchman had three careers. He started as a professional footballer with Dunfermline and Clyde before establishing a reputation as an academic lawyer specialising in public law. His final segue was into legal practice as a partner in prestigious law firms, first in Edinburgh and then in London. Prior to his untimely death he was a Professor at the University of Glasgow.

Editor Peter Robson completed the final draft of Paul’s The Fight for Rent Control. Peter is a former Professor of Social and Welfare Law and Judge in HM Courts and Tribunals Service.