By Joanna Hofer-Robinson & Pete Orford

The first critical edition to collect Dickens’s dramatic works, enriched with thorough scholarly notes that foreground primary archival research

Not every reader of Dickens’s novels will realise that he was also a playwright. And, even then, the general assumption is that he wasn’t a very good one. I don’t think that this is true. Here are five reasons why:

1. Runs

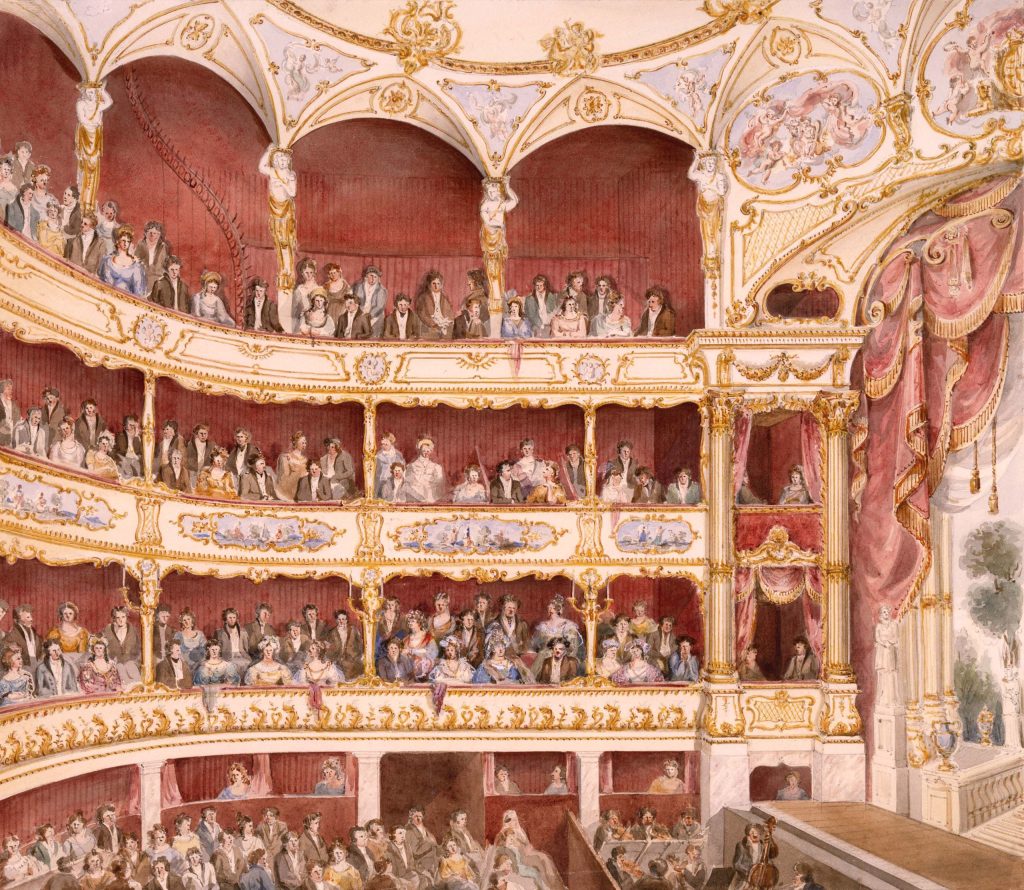

Dickens wrote in an age when the public’s voracious appetite for theatrical entertainment kept up a constant demand for new works. Unlike the long runs that we see in the West End today, theatre managers changed their programmes regularly and were always on the lookout for new material that could be rehearsed and staged at speed. The three plays that Dickens wrote for the fashionable St James’s Theatre in the 1830s did well by contemporary standards. His first and most successful play – The Strange Gentleman (1836), which adapted his sketch “The Great Winglebury Duel” – was played approximately seventy times over the course of the season and was revived the following year. It was also taken on tour to provincial theatres and produced at least twice in North America before the end of the decade.

2. Reviews

Although we can’t take theatre reviews at face value, Dickens’s plays were typically rewarded with positive write-ups in contemporary newspapers. Even his operetta, The Village Coquettes (1836), which is typically remembered as an unsuccessful attempt by Dickens to write for a different medium, was not uniformly lambasted by Victorian critics. The Sun called it ‘a light and elegant comedy, in which a great deal of gaiety and humour are blended with scenes of great interest, and many sweet and natural touches of tenderness and feeling’ (‘ST. JAMES’S THEATRE’, no. 13,799, 7 Dec. 1836, p. 3). In fact, the problem that reviewers cited was the difference between Dickens’s plays and his novels. The plays were perceived to be “unDickensian.” But surely this is only to be expected, when we consider that theatre is a collaborative artform, and typically missing a narrative voice?

3. Genre

Dickens’s works are good examples of the genres of Victorian popular theatre in which he wrote: melodrama, burletta, and farce. These are theatrical modes in which the playwright necessarily stays out of view, as the action is driven by the interaction between the dramatis personæ. Nevertheless, we see the influence of these genres in his literature: in the polarities of good and evil in his earlier novels, in the slapstick comedy and catchphrases, and in the ways that plots can turn on unlikely coincidences. Dickens’s confidence with theatrical modes thus fed the development of his idiosyncratic literary style.

4. Celebrity

Dickens’s first foray into playwrighting thrust him into a world where dramatists were not highly valued and typically did not make a lot of money. He was first engaged to write a piece for London’s fashionable St James’s Theatre before the Pickwick Papers made him a literary celebrity and it is possible to trace his emerging sense of his significant professional power through his interactions with this theatre, during the same period as Pickwick made him a star. Eventually, he priced himself out of his commitment, having become frustrated with the St James’s chaotic management.

However, he did not want to stop writing for the theatre in general, and approached the influential actor W. C. Macready instead. Macready’s rejection of his farce The Lamplighter (1838) appears to have severely affected Dickens’s confidence, and he did not return to playwrighting for some years. This exchange with Macready bespeaks the value that Dickens ascribed to the theatre, and also demonstrates that his literary fame was not necessarily a shortcut to theatrical success – it might even stand in his way.

5. Adaptation

Dickens was famously irritated by unauthorised adaptations of his works, for which he received no financial benefit, even while they achieved phenomenal popularity. In an effort to regain control over his imaginative property, he worked closely with professional theatres on authorised adaptations of his novels, and dramatized his own works for the stage. His last, co-written play was an adaptation of his and Wilkie Collins’s novella No Thoroughfare (1867), which was staged at the Adelphi Theatre in 1867. The practice of dramatizing his own works thus bookends Dickens’s literary career, with The Strange Gentleman at the start and No Thoroughfare at the end. Through this, Dickens placed himself in direct competition with other popular playwrights, and we should read his plays in the context of other contemporary works.

The Plays of Charles Dickens collects together for the first time all seven of the plays attributed to Dickens as sole or collaborative author. The critical edition allows us to explore how important playwrighting, and theatre more broadly, was to Dickens’s imagination and professional identity – and, I think, reading these plays in their context also shows us that he wasn’t really a bad dramatist.

About the authors

Joanna Hofer-Robinson is an Assistant Professor in the English and Comparative Literary Studies department at the University of Warwick. Her recent publications include Dickens and Demolition (2018) and Sensation Drama, 1860—1880: An Anthology (2019, co-edited with Beth Palmer), as well as articles on various aspects of nineteenth-century drama and Dickens studies.

Pete Orford is Course Director of the MA in Charles Dickens Studies at the University of Buckingham, and Academic Advisor to the Charles Dickens Museum in London. His recent publications include The Life of the Author: Charles Dickens (2023) and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Charles Dickens’s unfinished novel and our endless attempts to end it (2018).