Bites of Aristotle ‘recasting’ Philip K. Dick

By Giulia Clabassi

Have you ever experienced something during sleep that felt more real than reality itself? Perhaps involving a friend, your grandfather, or a cat you had in your childhood? Well, Aristotle tells us what might have happened in your restless night in a passage from On Dreams (Gallop 461b7-30):

Bite 1:

‘Now, just as we said that different people are prone to deception on account of different emotional states, so is the sleeping person on account of sleep, because his sense-organs are being moved and because of other circumstances attending perception. Consequently, what bears a slight resemblance to something appears to be that very thing. For whenever one is asleep, as most of the blood sinks down to the starting-point, the movements present within it — some potentially, but some actually go down with it. They are so disposed that in any given movement of the blood, one movement will rise from it to the surface; and if that one perishes, then another will do so.’

Bite 2:

‘In fact, relative to one another, they are just like those artificial frogs that float upwards in water as the salt dissolves — just so, the movements are there potentially, but become activated as soon as what impedes them is removed. Upon being released, they move in the little blood remaining in the sense- organs, while taking on a resemblance, as cloud formations do, which people liken now to men and now to centaurs as they change rapidly. Each of these, as has been said, is a remnant of the actual sense- impression, and is still present within, even when the real one has departed.’

Bite 3:

‘Thus, it is true to say that it is like Coriscus, even though it is not Coriscus. While one was perceiving, one’s ruling and judging part was saying not that the sense-impression is Coriscus, but because of that impression, that the actual person out there is Coriscus. The part that says this while it is actually perceiving (unless it is completely held in check by the blood) is moved by the movements in the sense- organs, as if it were perceiving. Consequently, what is like something is judged to be that very thing. And the effect of sleep is sufficient to make this escape notice.’

Coriscus can be the friend whom you felt was real, except that one is the real Coriscus (hoping that you have a friend with this name), and the other is just like Coriscus (some distorted image of him).

So, what is Aristotle actually saying?

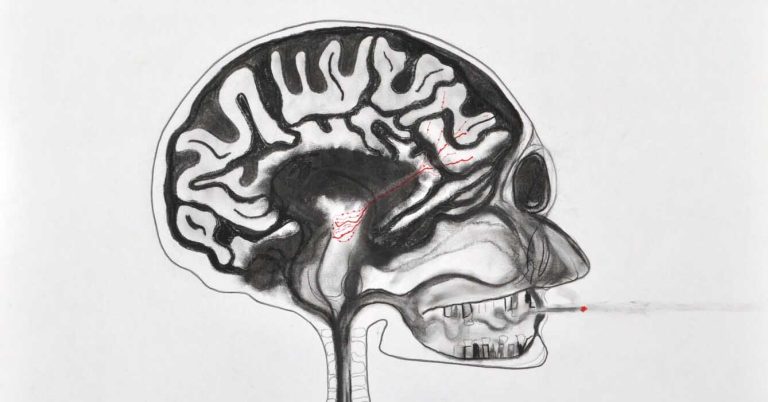

Roughly, it goes this way. Aristotle introduces the problem of understanding images in sleep by telling us that people are vulnerable to deception due to emotional states, and, in the same way, the sleeping person is deceived because the sense-organs are ‘altered’ in such a way that it leads to deception (bite 1). Imagine you are going to sleep, and your sense organs (e.g. your eyes, your ears, etc.) are not entirely inactive. The blood continues to flow through them, and this movement can trigger images in the brain.

However, these sensations are not real perceptions of things happening around you in the present; instead, they are leftover impressions. The mind, while asleep, may mistake these images for real, actual experiences, even though they are just echoes. Aristotle also refers to some kind of ‘flow’ of the bloody movements: some of them go down only potentially (we can think about this in terms of capacity) and others actually (here in terms of realization or ‘the action by which something passes from possibility to full and complete reality’, as Menn argues). Aristotle adds that, if the first movement or wave of blood dissipates or stops, another movement can take its place, continuing to trigger images and keeping the sensory experience ongoing (as in a cycle).

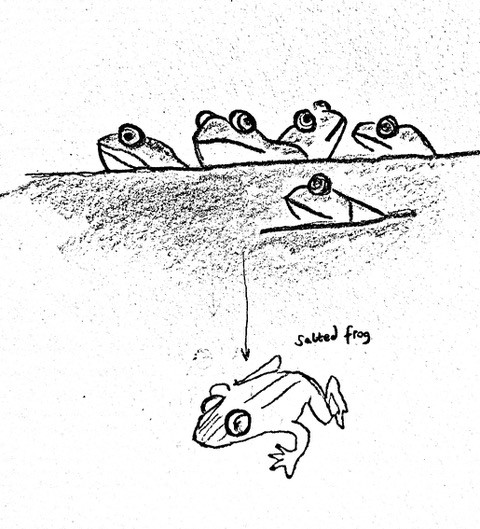

A game of artificial frogs

Then (bite 2), Aristotle’s magic starts flowing. He compares these movements (or more precisely, the relationship in which they stand) to artificial frogs (peplasménoi bátrachoi in Greek) floating in the water when salt dissolves. Even if this were an ancient game, it is quite a strange game!

Here is an image of one way in which the artificial frogs containing different amounts of salt are immersed in water. Philip van der Eijk suggests that the frogs are made of clay (233-234). Due to the salt, they sink. However, when the salt dissolves in the water, the frogs rise to the surface, one after another, depending on the amount of salt with which they were coated. The salt is described by Aristotle as ‘the impediment’ that hinders the ‘going up to the surface’ of the frogs. Remove the impediment, and the circus of images is activated.

Aristotle: the first science-fiction writer?

This is the ‘science-fiction’ (to use a modern term that reminds us of the boundaries between men and machines in Philip K. Dick’s 1968 dystopian novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) analogy that highlights our inability to exercise our normal brain functions. Aristotle associates this trick with people who often see shapes in clouds (‘as cloud formations do’) and mistake them for a certain figure (such as a man or a centaur). It’s when you’re bored in the car due to heavy traffic and you decide to play the little ‘cloud game’, trying to catch extravagant shapes in the clouds (obviously not the driver, though; drive safe!). It is always either this game or ‘I spy with my little eye’, in which our friends need to guess exactly what we are observing based on a few descriptions.

You might recognize that similar deceptions about sleeping can happen when we feel as if we are ‘falling down’ during sleep, which is sometimes accompanied by a physical jolt. This is an impression generated by the body when physical signals (such as blood movement or muscle relaxation) are misinterpreted by the brain as an actual fall. Perhaps this is even more vivid than just an image.

Aristotle (bite 3) concludes that it is true for us to say that the image of our friend Coriscus is like seeing a faint image or shadow of Coriscus in our mind, which looks like him but is not Coriscus himself. When we perceive something, our mind (the ‘ruling and judging part’) interprets the sensation and concludes that the real Coriscus is in front of you; this is why I woke up a long time ago thinking that my little kitty Spike was actually still sleeping with me. Now we know that our ‘ruling and judging part’ is a victim of the action of frog-like movements within the individual! However, we can remain ‘safe’ from these illusions if the blood-flow ‘blocks’ the sensory movements, preventing the mind from being tricked into misinterpreting sensations as reality (as Aristotle appears to suggest in the brackets). Are these just normal situations where our ‘froggy movements’ are salted and at peace? I will leave this question to the reader.

Further reading

Gallop, David, translator. Aristotle: On Sleep and Dreams. By Aristotle, Aris & Phillips Ltd, 1996; 2015.

van der Eijk, Philip, translator. Aristoteles De insomniis, De divinatione per somnum übersetzt und erläutert. By Aristotle, Akademie Verlag, 1994.

Menn, Stephen. ‘The Origins of Aristotle’s Concept of Ἐνέργεια: Ἐνέργεια and Δύναμις.’ Ancient Philosophy, vol.14, no.1, 1994, pp.73-114.

About the author

Giulia Clabassi is originally from Rome, Italy. She recently completed her PhD at Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, and is currently preparing her thesis for publication. Her research focuses on the nature of motion as explored in Book VIII of Aristotle’s Physics, blending her interdisciplinary expertise across ancient philosophy, the philosophy of science, and the history of science and technology. She has recently contributed to the book review section of Issue 6.2 of Ancient Philosophy Today.

About the journal

Ancient Philosophy Today: DIALOGOI provides a unique venue in the profession for the publication of excellent work in ancient philosophy which engages, in content or in method, with contemporary philosophy. It also publishes excellent work in contemporary philosophy which significantly draws on ancient philosophical ideas.

Sign up for TOC alerts, subscribe to Ancient Philosophy Today, recommend to your library, and learn how to submit an article.