Gilles Deleuze was born on 18 January 1925, meaning that 2025 marks the centenary of his birth. Throughout 2025, we’ll be celebrating the impact of this towering figure in twentieth-century philosophy.

Let’s kick off with a blog post from Ian Buchanan, editor of both the journal Deleuze and Guattari Studies and the book series Deleuze Connections and Plateaus – New Directions in Deleuze Studies. Look out for more Deleuze-related posts throughout this centenary year!

Find out more about our centenary celebrations.

By Ian Buchanan

Deleuze died two months after I submitted my PhD in 1995. These events are not necessarily related, but it did mean that this particular farm boy who grew up on the outskirts of Perth, Western Australia, proudly the most isolated capital city in the world, never got to meet his idol. I was not among those moved to tears by his death, not out of any lack of feeling I hasten to add, but because Paris was an impossibly distant place to me. It was so ‘over there’ that the there did not seem real. The biggest gap in, and the real failing of, the various histories of so-called ‘French Theory’ published in recent years, is that they do not account for – or, even address – the attraction Deleuze, Derrida, Foucault, and so on, exerted in far flung places like the antipodes where French is largely untaught and philosophy is resolutely analytical.

Thirty years later, in the centenary of Deleuze’s birth, not much has changed on that front. French still isn’t much taught, and philosophy is still largely analytical. Yet interest in Deleuze’s thought has grown exponentially, reaching literally every corner of the world, including many places with even less interest in either French or continental philosophy than one finds in Australia. For instance, Deleuze has a large and growing readership in China, India, Indonesia, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, where there is no obvious cultural reason that this should be so, save a broad interest in European intellectual traditions. The surprising and historically noteworthy thing is that it is in these places, where you’d expect Deleuze’s thought to be as productively received as fertilizer on cement, that it thrives rather than in the country that claims him as one of their own. Deleuze’s influence in foreign parts cannot be attributed to the ‘have theory, will travel’ approach taken by Derrida and Foucault (among others). Deleuze stayed home, but his thought had wings.

There are, I think, two explanations one might give to explain the broad appeal of Deleuze’s thought. The first trivial, but not therefore wrong, and the second historical, but not easily demonstrated. The trivial answer is that Deleuze’s work has never demanded that anyone adhere to a particular methodology or way of thinking; on the contrary, he exhorts everyone to strike out on their own and do their own thing. There could hardly be a form of thought that was more consonant with the self-centered imperatives of late capitalism than this! Which is why it is a trivial and something of a dangerous answer, since it seems to confirm the damning indictments of Zizek and others who regard Deleuze’s work as something that only appeals to yuppies. In a moment I’ll say why this line of criticism of Deleuze is wrongheaded, but before that I want to briefly illustrate why this liberating aspect of Deleuze’s thought has meant that it continues to soar even as the stocks of his contemporaries have started to wane.

The most cited scholar in the world is Foucault because he created concepts we could apply to the world around us – once you start looking for them panopticons are everywhere! But no one can really emulate his way of working because, to adapt a line from Oscar Wilde, it would require far too many mornings buried in an archive. By contrast, everyone can ‘do’ Derrida – once the second most cited scholar in the world – because the premise of deconstruction – that nothing is ever fully what it claims to be or seems – can be applied to anything without a great deal of thought being put into it. Interest in deconstruction declined quickly after the master died because no one could satisfactorily answer the ‘so what?’ question it left hanging. Baudrillard suffered a similar fate because once you’ve acknowledged that everything is a simulacrum of a simulacrum there’s not a lot left to do except congratulate yourself for not being taken in by appearances. Similarly, Lyotard named an epoch and said there was nothing left to believe in, thus giving us nowhere to go. Meanwhile, Badiou, as Deleuze and Guattari hinted, is so complicated no one really knows what he is on about. We can all feel clever by citing him, but this is the intellectual equivalent of eating fast food: it tastes good for a while but leaves you feeling empty afterwards. Lastly, the ‘French Feminists’ (as Liz Grosz called them) haven’t endured because they were largely blind to issues of race, ethnicity, class, and the plasticity of gender itself.

Let me turn then to the second explanation. ‘Always historicize!’ the recently departed Fredric Jameson said in a book that proclaimed to want to follow Deleuze and Guattari’s thinking. What does a historicized Deleuze look like? This is a question we haven’t asked enough in my view. If Foucault had said it was this century that would one day be known as Deleuzian, then the years since Deleuze’s death would certainly have proven that prognostication correct. But it was the previous century that he was referring to and he had in mind something besides fame and influence. It is my sense that the appeal of Deleuze’s thought today can only be explained in terms of its resonance with what happened in the latter half of the 20th century. If one takes the advent of neoliberalism, the collapse of communism, decolonization, sexual liberation, the rise of digital technology, and the move to a globalized economy, among other such culturally tectonic shifts as the start of ‘our’ century, then it is precisely this century that Deleuze’s work speaks to.

A legacy to continue

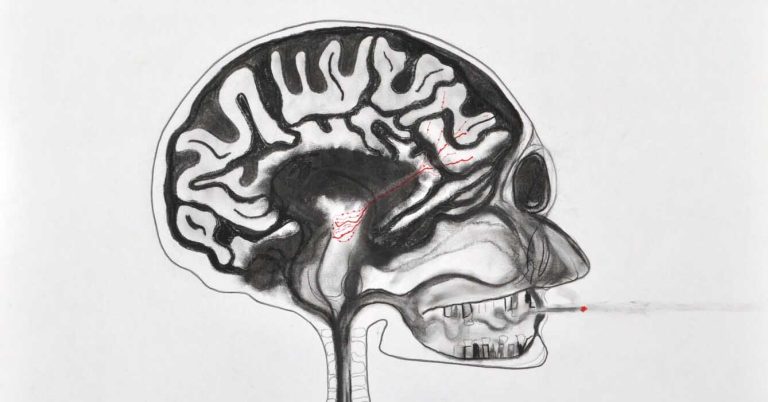

Towards the end of his life Deleuze said in interviews that he and Guattari had always remained Marxists, as though it was somehow in doubt. They explicitly eschewed a return to Marx in the manner espoused by their contemporary Althusser, but in contrast to Foucault they never sought to disavow their connection. What they foresaw with remarkable acuity and attempted to map with the array of new concepts they created is the explosive impacts of capitalism’s tearing-up of the social contract in the late 1960s and early 1970s. They correlated it with schizophrenia because they could see that the changes were occurring in the very fabric of reality itself – all the traditional expectations about what government should do and how businesses should be regulated were shredded. Desire was the lure, the victim, and the beneficiary of these changes, they argued, and with concepts like the desiring-machine they helped us to see this. To my mind, this project remains productively incomplete and their real legacy is the sense that it is work we can continue for ourselves using their tools and by inventing others.

About the author

Ian Buchanan is Professor of Cultural Studies and Critical Theory at the University of Wollongong, Australia. He is the founding editor of the journal Deleuze and Guattari Studies and the author of The Incomplete Project of Schizoanalysis (Edinburgh University Press, 2021) and Assemblage Theory and Method (Bloomsbury, 2020). He is also a series editor of the Deleuze Connections and the Plateaus series, both published by Edinburgh University Press.

Find out how Edinburgh University Press is celebrating 100 years of Gilles Deleuze

The blog contains a replica of what Marx and Bloch say about the French Revolution: “the emancipated egotistic individual.” The French Revolution was essentially a bourgeois thing. The people did not understand freedom. They were given freedom of religion, which they construed as freedom from religion; property ownership rights, but not freedom from property.

“If one takes the advent of neoliberalism, the collapse of communism, decolonization, sexual liberation, the rise of digital technology, and the move to a globalized economy, among other such culturally tectonic shifts as the start of ‘our’ century, then it is precisely this century that Deleuze’s work speaks to.”

If these are tectonic shifts and not the total alienation of Man and his freedom, then another false dream is presented by “the emancipated egotistic individual.” Deleuze’s Spinoza and their understanding of “practical philosophy” have a different ring to them, especially when one reads them in a religiously weaponized society like mine (Pakistani Muslim).