By Thomas Archambaud

On 17 February 1796, the Scottish writer James Macpherson (1736-1796) died in his home in the Scottish Highlands. Known internationally for his ‘translations’ from the Gaelic Bard Ossian, James has been considered a key figure of the pre-romantic movement. But to his neighbours, he was a man closely associated with the gruesome business of Empire.

A political animal

James grew up in Brae Ruthven, a township in the ancient county of Badenoch, Inverness-shire. Educated at King’s College, Aberdeen, he moved to Edinburgh. Then relocating to London, Macpherson published the best-sellers Fingal (1761) and Temora (1763). Patronised by the 3rd Earl of Bute, he was later appointed colonial secretary in West Florida and became involved in Britain’s colonial economy.

After his return to London in 1767, James worked simultaneously as pro-governmental writer, lobbyist for the English East India Company (EIC) and private agent for the Indian Nawab (prince) Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah. Although he never set foot in India, James took a direct role in the Company’s territorial expansion, later confirmed by his election at the House of Commons in 1780.

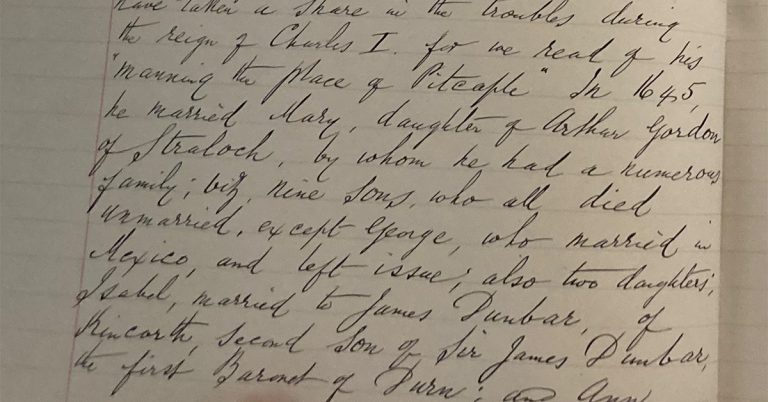

The clan champion

James’s colonial connections enabled him to serve the interests of his clan, who suffered a lot following the confiscation of clan chief Ewen Macpherson of Cluny’s estate after his participation in the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. James supported, among many other members of his clan network, the military career of Ewen’s son, Duncan, in Northern America. ‘I have almost depopulated that Country by sending officers and men of the clan into the army’, James admitted in 1779.

After intense negotiations between James and government officials, such as Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, Duncan had his estate restored in 1784. He celebrated by hosting memorable parties in Badenoch and London, while James was considered the new clan champion.

A nouveau riche

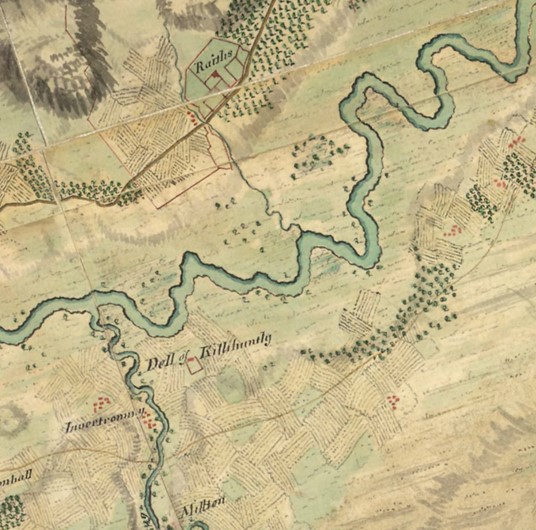

James also wished to return to his native country. In 1780, he bought the Raitts estate north of Kingussie, to which he gave the fashionable name of ‘Belleville’. He also commissioned a neo-Palladian mansion designed by the most famous architect of the day, Robert Adam (1728-1792). The Georgian interior, in a critical state today, once housed objects and designs celebrating Macpherson’s wealth derived from India.

Clan Macpherson Museum, Newtonmore.

A paternalist landlord

James took the management of Raitts very seriously. He improved the layout of his estate by planting trees, but his motivations were not aesthetic. His forest management on the hills of Creag Bhuidh helped to develop the wood industry which is still vital to the region’s economy today. On his lands, he never conducted clearances, the disastrous consequences of which for the population and the environment are well-known.

For James, the priority was to instrumentalise Gaelic culture to justify his re-establishment as a gentleman farmer, an attitude which occasionally verged on megalomania. His tenants called him ‘Ossian’, or ‘Fingal’, a flattering comparison to the warrior featured in his publications. His friend John Anderson, the local minister of Kingussie, described James’s house as Fingal’s palace, the ‘Halls of Selma’. Through rhetoric and entertainment, James had become the cultural authority of Clan Macpherson.

An improver in disguise

Despite his commitment to the preservation of the territorial and cultural dimensions of clanship, James, like his friends of the Edinburgh Enlightenment, shared the belief in agricultural modernisation. He did not hesitate to encourage his kinsman Robert Macpherson of Benchar, former military chaplain in Quebec, to evict tenants, replace them with sheep, and embrace the brutal values of agrarian capitalism. The reason for James’s resistance to clearances in Raitts was not humanitarian but motivated by a desire to protect his own reputation. Since his main income depended not on agriculture but on colonial profits, James was under no pressure to make the estate profitable.

In fact, James spent most of his time in London, the capital of the British Empire. Despite his efforts to re-indigenise external capital from India, James’s interests lay with the colonial elite and London MPs. The erection of an obelisk, for which James left the comfortable sum of £500 in his will, made no illusion about his politics, and the radical transformations of the Badenoch landscape introduced by his association with India.

Far from the romanticised figure of the sentimental Highlander, James Macpherson’s return to Badenoch tells the story of a man who self-consciously forged his own myth based on Ossianic poems and his reappropriation of Gaelic culture. By facilitating the integration of the entrepreneurial Macpherson gentry at home and in the Empire, James created a new culture of clanship which established himself as a benevolent and paternalist landowner. His involvement with the East India Company, however, testifies to the tremendous and brutal changes introduced by the British Empire in the Scottish Highlands in the second half of the 18th century.

Image credits:

- Fig. 1: Image courtesy of University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums, ID: JV-5151.

- Fig. 2: Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 5804.

- Fig. 3: Image copyright of Thomas Archambaud, 2019.

- Fig. 4: Image accessed from National Library of Scotland.

- Fig. 5: Image copyright of unknown author, 2016.

Read Thomas Archambaud’s latest article in Northern Scotland

About the Journal

Northern Scotland is a cross-disciplinary publication which addresses historical, cultural, economic, political and geographical themes relating to the Highlands and Islands and the north-east of Scotland.

Sign up for TOC alerts, subscribe to Northern Scotland, recommend to your library, and learn how to submit an article.

About the Author

Based at the University of Glasgow, Thomas Archambaud has recently submitted a Ph.D. on the global and European connections of the clan Macpherson in India, c. 1760-c. 1802. His doctoral research has been supported by the Graduate School for Arts and Humanities, the Scottish Historical Review Trust, with the collaboration of the Centre Roland Mousnier (Sorbonne-Université).

Explore related articles on the EUP Blog

Adam Smith and Scotland in the Age of Enlightenment

The role of heritage in community development of the Highlands and Islands

Remembering the history of Scottish land reform

Introducing Northern Scotland: Black Lives Matter Virtual Collection