by G. Connor Salter

I knew that he put the word “geek” into popular culture with his 1946 novel Nightmare Alley. Beyond that, the only thing I knew when I started researching William Lindsay Gresham was that his ex-wife, Joy Davidman, later married C.S. Lewis. My research into what Gresham felt about the Inklings, the Oxford writers’ group that Lewis belonged to, led to my recent essay What Are Magic and Myth Good For? Exploring William Lindsay Gresham’s Memories from Oz.

My essay focused on Gresham’s 1960 article in the Baum Bugle that described his marriage ending and offered some Inklingsesque ideas about loss, hope, and fantasy literature. By the time I’d finished the essay, I knew there was much more to Gresham than just being a side figure in Inklings discussions.

1. He wrote about the Inklings

Gresham knew and wrote more about Lewis and his friends than often assumed. Letters from Gresham to Davidman show he was familiar with J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. He wrote an introduction for a 1950 edition of Charles Williams’ novel The Greater Trumps and an insightful review of Williams’ The Place of the Lion for The Saturday Review in 1951.

While reading Gresham’s papers at the Marion E. Wade Center in 2023, I discovered Gresham wrote a poem about C.S. Lewis called “The Friar of Oxford.”

2. He has a funny place in crime fiction

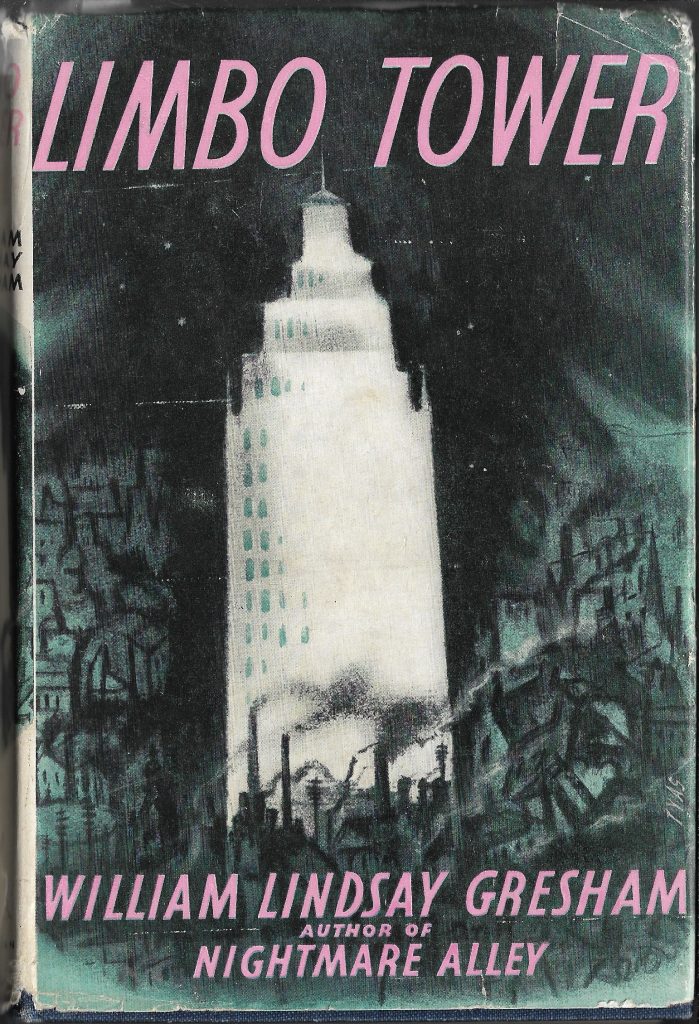

Nightmare Alley gave Gresham an important place in the second wave of hardboiled (or noir) novelists, post-WWII writers like Jim Thompson and David Goodis. Yet he’s a curious outlier in the second wave, which may explain why he’s under-researched.

As Ed Gorman explores in The Big Book of Noir, this wave of writers often faltered in the hardcover market and survived through paperback originals—cheap crime novels with suggestive covers. Nightmare Alley was a hardcover bestseller, putting Gresham above the paperback originals market that accelerated a few years later when Fawcett started their Gold Medal imprint. Highbrow success gave him fame but also meant he never joined the business pipeline that sustained his contemporaries.

3. He had surprising friends

Historians on stage magic know that Gresham wrote a 1959 biography of Harry Houdini and was friends with Clayton Rawson and John Dickson Carr, both known for mystery novels featuring magic. However, he had wider connections. Sci-fi writer Robert A. Heinlein quotes him in his novel I Will Fear No Evil and his essay collection Expanded Universe. Abigail Santamaria showed in her Davidman biography that Gresham taught Spanish Civil War songs to Pete Seeger in Greenwich Village in 1940. Clark Sheldon reports that Gresham corresponded with such famous authors as Robert Bloch and L. Ron Hubbard.

4. The FBI kept reports on him

Many researchers struggled to determine why Gresham sometimes referred to his former partner, Jean Karsavina, as his wife. No marriage certificate has been found, but since they were both American Communist Party members in the 1930s-1940s, rumor had it the FBI had files on them. Sheldon informed me that he requested the file on Karsavina and was told it was destroyed or never existed.

I eventually learned that the FBI sent a copy of the Karsavina file to Perry C. Bramlett (1945-2012), and was able to see a few pages. A February 8, 1955 report by FBI informant Mark Iden stated that Karsavina “appeared to be married” (common law spouse) to Gresham during the 1940s. Gresham moved out of Karsavina’s apartment in 1940, and “following his departure the subject explained that she asked William Lindsay Gresham to leave because he was not behaving himself with other women, who attended her social gatherings.”

Ironically, Karsavina was present at an event where Gresham may have met his future wife: he, Karsavina, and Davidman all attended the League of American Writers’ Fourth Annual Congress in 1941.

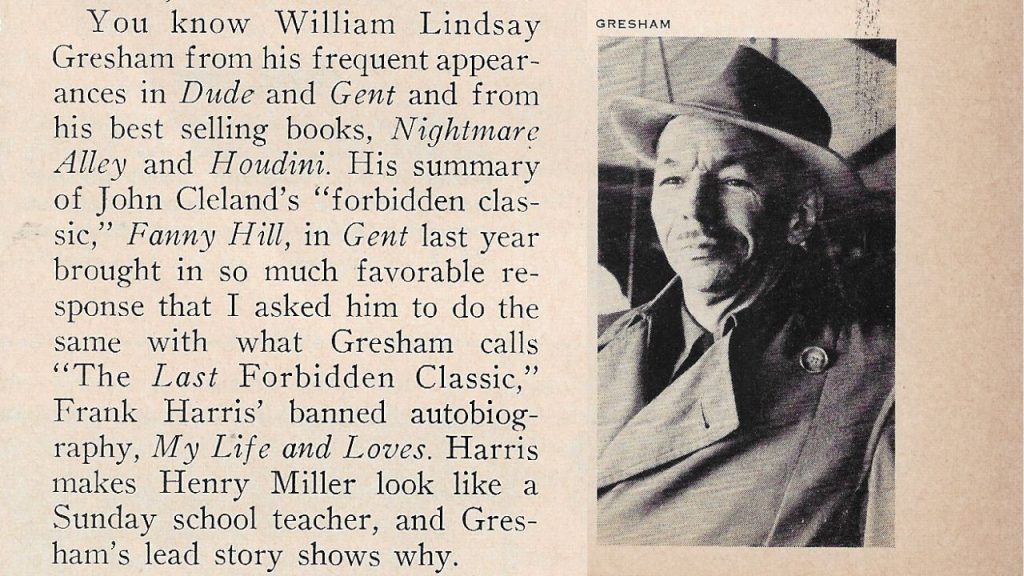

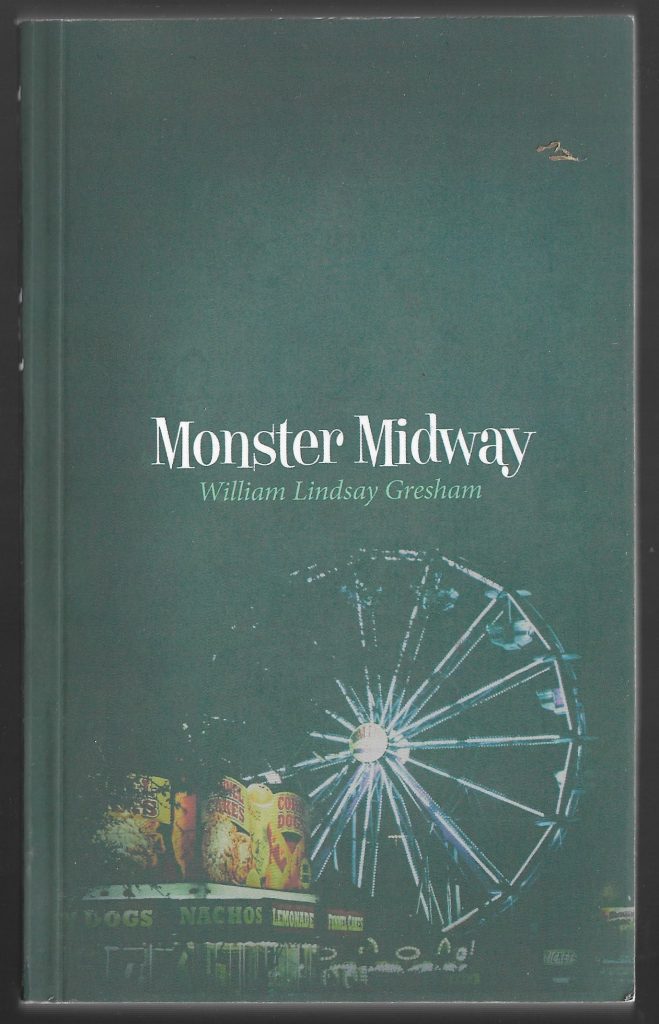

5. We’re not sure how much he wrote

Like many writers struggling for work in the 1950s, Gresham published short stories and articles in men’s magazines with titles like The Dude. As Bret Wood explains in his introduction to the Gresham collection Grindshow, that makes it hard to say how much Gresham published. Many writers contributed anonymously or under pen names to numerous men’s magazines owned by the same publisher. Currently, I am seeking magazines that feature Gresham’s writing so researchers can analyze the issues for unidentified pieces fitting Gresham’s writing style.

There’s plenty still to explore about Gresham. He intersected with some of the most interesting cultural movements of his day: the American carnival business, the Spanish Civil War, the early American Left, the Greenwich Village folk music scene, the golden age of American science fiction, and the second wave of noir. Even the Inklings. I’m hoping my research will encourage others to explore further.

I’d like to thank Bret Wood, Robert Nedelkoff, Clark Sheldon, and the estate of Perry C. Bramlett for their help exploring these topics.

About the journal

The Journal of Inklings Studies provides a forum for rigorous academic engagement with the work of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, Owen Barfield, and their literary circle.

The journal’s two principal aims are to lead and support the growing field of C.S. Lewis and Inklings Studies, and to test and develop the potential of C.S. Lewis and his circle to be serious intellectual conversation partners for scholars in literature, philology, theology, and philosophy more widely.

About the author

G. Connor Salter is a divinity student at St. Mary’s College, University of St. Andrews. His research on William Lindsay Gresham has appeared in Mythlore, Punk Noir Magazine, Fellowship & Fairydust, and other publications.