by Marissa Greenberg and Elizabeth Williamson

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing US institutions of higher education is the tension between an increasingly diverse student body and an inherently (and inherited) homogenous curriculum. “Meeting today’s students where they are” is a common response, but to achieve this goal for students, our institutions will need to make good on their promises to support faculty who are committed to social justice. In English departments and premodern literary studies specifically, it will also require having the backs of faculty who resist the ways that Shakespeare has been used to police educational boundaries. Just as we seek to connect students with institutional resources focused on their well-being, our authors provide a powerful model of what it looks like to sustain each other between and across institutions, as we struggle to design classrooms where we can tell the truth about Shakespeare, our situations, and ourselves.

1. Situating multiple points of access helps us to resist the famed universality of Shakespeare’s plays

Scholar-teachers of Shakespeare anchor their pedagogies in lived situations: geographical, institutional, personal. In practice, their pedagogy leads to similarly varied and embodied points of access, including physical locations, virtual resources, regional histories, and local and global communities. For teachers who seek to resist the weaponization of Shakespeare’s universality – often because they themselves have been on the receiving end of exclusionary practices – our authors provide a roadmap for prioritizing students’ own situated engagement with the literature. The practical strategies they offer include introducing students to historical costumers of color (Penelope Geng’s chapter), ensuring that low-income students have access to high-quality online resources (Victoria Mũnoz’s chapter) and co-creating ecocritical performances (Katherine Steele Brokaw’s chapter). All of these strategies uncover and build on the wisdom of students who have been told that Shakespeare is not for them or that they have to love Shakespeare in ways that deny their lived experience.

2. Not replicating exclusionary institutional practices is the work of not only Shakespeare scholarship but also Shakespeare classrooms

Given the charged history of Shakespeare studies, and of higher education in the US more broadly, creating genuinely accessible learning environments requires breaking down the walls between campus and community, including building bridges with non-academic institutions. By situating Shakespeare in this way, scholar-teachers can link the legacies of early modern literature to present-day injustices. Student projects that embrace protest (Elisa Oh’s chapter) and syllabi that center regional adaptations of the plays (Katherine Gillen and Kathryn Vomero Santos’s chapter) are just two of the ways our authors organize this work in their classrooms. Through these approaches, our authors engage students in wider critiques of higher education by understanding and building on the specific political and cultural skill sets students bring with them into the Shakespeare classroom.

3. Acknowledge that this work can take a significant toll, especially on minoritized and other at-risk faculty, but reading about how they manage professional risks and feelings of unbelonging can bolster our resistance

The authors in this volume are remarkably candid about their own experiences of exclusion, but they are also exceptionally creative in the ways they use those experiences as fuel for their radical pedagogical approaches. They explore silence as a space of possibility in classrooms led by biracial scholar-teachers and with mixed race students (Roya Biggie and Perry Guevara’s chapter). They embrace rudeness as a tactic of disruption (Eric De Barros’s chapter) at institutions comfortable in their white male Christian privilege. And they foster love (Amrita Dhar’s chapter) and discomfort (Kirsten Mendoza’s chapter) as equally important affective relationships to Shakespeare and early modern literature. Our authors show how such relationships are necessary to ethically informed, politically responsive pedagogies (Mary Janell Metzger’s chapter) that find a place for all students within larger systems of knowledge production and cultural reproduction.

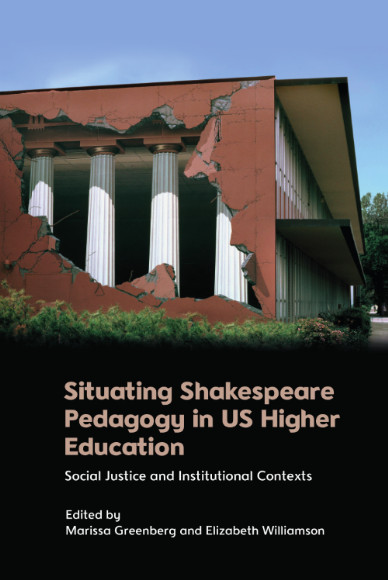

For more information about strategies for situating your social justice-oriented pedagogy, see Situating Shakespeare Pedagogy in US Higher Education: Social Justice and Institutional Contexts, available from EUP in hardback and ebook formats.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the book

Moves away from offering a single methodology or approach to social justice teaching, providing practical models for academics to follow

Building on the recent surge of interest in equitable pedagogy within the field of Shakespeare and Renaissance literary studies, Situating Shakespeare Pedagogy in US Higher Education makes a case for anchoring our teaching in these institutional power dynamics that have historically contributed to systemic injustice and continue to affect our work on a daily basis.

About the authors

Marissa Greenberg is an associate professor of English at the University of New Mexico.

Elizabeth Williamson is a former faculty member and dean at The Evergreen College.