by Luke O’Sullivan

Tell us a bit about your book

Categories is all about things you can’t see or touch but use all the time. We’re always drawing lines and dividing up the world, not to mention classifying people, in one way or another, but we’re often not very conscious of how or why or even that we’re doing it. We’re walking around oblivious to the spectacles on the end of our noses but dependent on them at the same time. Categories are the concepts that provide us with the invisible frameworks in terms of which we make sense of everything. But what’s a category, actually? It turns out there have been quite a few different answers to that question; the book tries to detail some of the most important.

What inspired you to research this area?

I got interested in how we tell one thing apart from another. What makes a claim scientific, for instance? How do we tell a historical statement apart from a political one? And so on. Different kinds of knowledge claims don’t announce their status. The world doesn’t come with labels on its face. And yet we typically recognise there are a variety of ways of speaking and thinking about things, from school timetables to bookshops. So what are those distinctions based on? I wanted to find some answers.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

Realising that it intersected with a number of important current debates about politics and knowledge. You could say that we’re wrestling with the question of what’s particular and what’s universal on any number of fronts. What do all human beings share? What is peculiar to certain cultures? To what extent do the problems of people in the past remain our problems now? It gave me the opportunity to engage with some very large questions.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

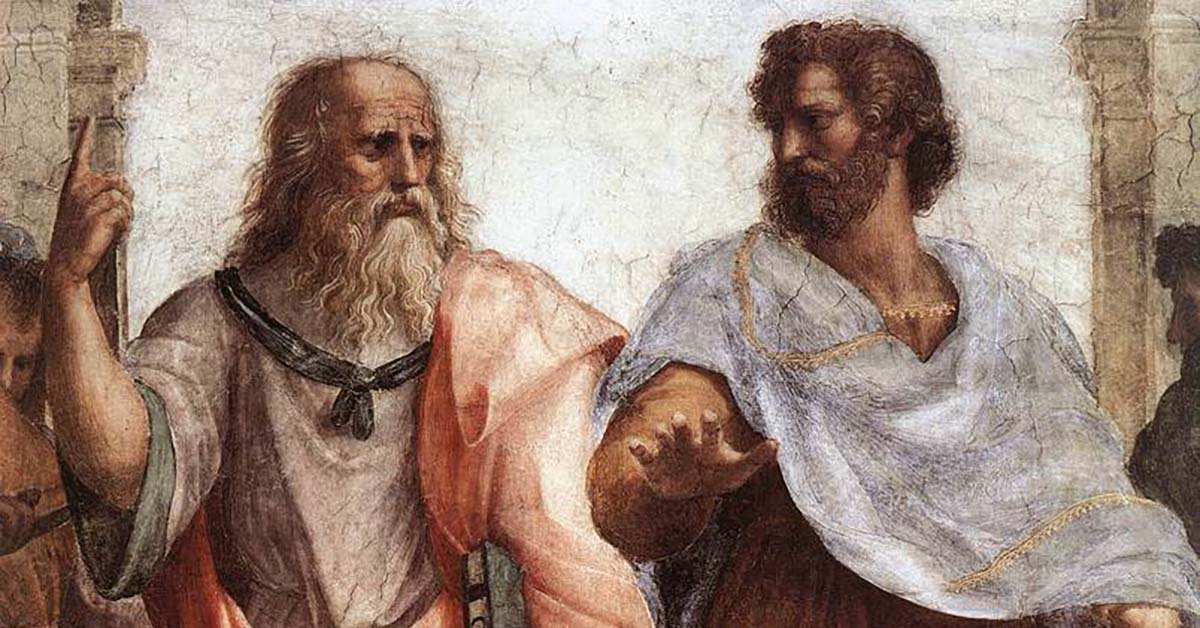

I was surprised by how much the questions that ancient philosophers were trying to answer are still our questions, and by how much our answers to them differ. Everyone tells you Plato was a genius, for instance; but I didn’t really feel why for myself until I realised that he was trying to explain how we make sense of the visible in terms of the invisible. That was a flash of complete brilliance on his part. You may not like his answer (his theory of Forms); but we’ve never got past the problem. It’s more that we’ve appreciated it has dimensions that weren’t obvious to thinkers in earlier times.

Did your research take you to any unexpected places or unusual situations?

Not geographically speaking. It did take me to some unexpected places mentally, though. You start to wonder if you’re a fraud when you work on something for so long without finishing it. It probably took me almost twenty years to get it done. I went down so many rabbit holes that I was in danger of never coming out again, although to be fair there was an awful lot that I needed to master even to write what I did in the end. But initially I had a wildly ambitious plan to write a complete intellectual history of categories and classification, and it slowly dawned on me that I’d probably die first. I think that what I originally envisaged might now be beyond the reach of any single scholar; it was certainly beyond me. So in the end, I had to scale back my ambitions. The result was more like a greatest hits compilation although one that tried hard to be historically respectful. But I think it was still an achievement to have put together some sort of overview to go alongside some very accomplished but more specialised studies.

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

Yes, insofar as I’m inclined to see problems to do with categories and classification as having a role in more or less any issue whatsoever. The book tries to show how our ideas about categories are connected to how we think about knowledge, politics, and history in particular. But that’s by no means an exclusive list of the ways in which categories are important. At the same time, doing this sort of work risks turning you into a monomaniac, so you have to guard against reducing everything to a version of your own favourite subject.

What’s next for you?

The only way to fill the void left by completing a book is to try to write another one. I’ve started trying to develop one of the major themes in Categories, namely the relative neglect of historical thinking in Western philosophy and Western culture more generally. The working title is Past Problems. You could say it’s taking up Nietzsche’s question of the uses of history for life. As someone once said to me, why should you care about a bunch of things that have already happened? At the time, that left me floored. But actually, I think there are some good answers that you can give to that question.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the author

Luke O’Sullivan is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the National University of Singapore. He has published articles in the fields of intellectual history, the history of philosophy, and visual culture. His monograph entitled Categories: A Study of a Concept in Western Philosophy and Political Thought was published with Edinburgh University Press in July 2024.

About the book

Categories establishes an enduring relationship between theories of categories and ideas about knowledge, politics, and history.

In ancient and modern Western thought, the problem of the nature of categories has been inseparable from arguments about the nature of selfhood; about how knowledge is organised; about how power should be distributed; and about how history should be understood. Luke O’Sullivan shows how these answers have gone forward into the contemporary era, and identifies three key schools of thought that have developed since Hegel in particular. He explains modern thought as a tension between a desire for a single dominant perspective, whether scientific or phenomenological; a belief in irretrievable fragmentation; and an effort to find a middle ground.