by Alasdair Grant

I would like to introduce you to two people. The first of these was called Iohannes Glafchyrno. Glafchyrno appears in the historical record for a split second in the year 1306, when the notary Angelo de Cartura drew up a document on Crete, then ruled by Venice, recording that he had been manumitted (freed) from slavery. This document, although only one of many such surviving manumission texts, is remarkable for the potted history it supplies of Glafchyrno’s tribulations. He was a Greek man from the town of Ephesus in western Asia Minor, which had recently been conquered from the shrinking Byzantine Empire and come under the rule of a Turkish prince. The man who set Glafchyrno free was called Hemanuel Virino, but he was not Glafchyrno’s first master. Before that, Glafchyrno had been captured by a certain Marcus Belliparo, who had undertaken a raid in consort with three Turkish galleys. Now, after some undisclosed time in slavery, Virino gave Glafchyrno his freedom on the condition that he supply him with labour every August for the rest of his life; presumably, this meant agricultural labour at harvest time.

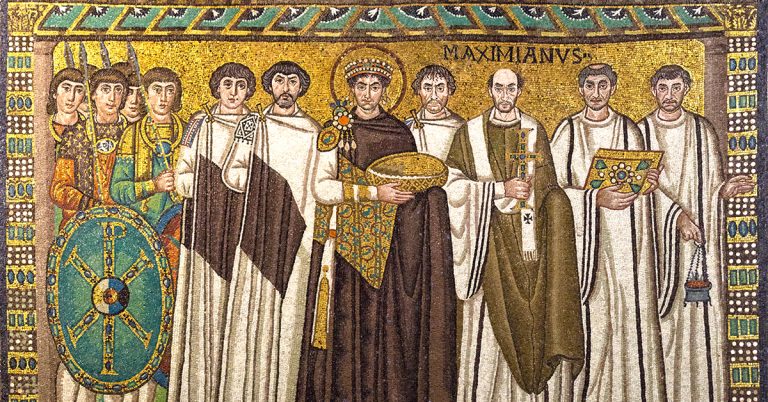

In the early years of the fourteenth century, Ephesus was the epicentre of a crisis of captivity among Greek Christians. A wave of Turkish conquests along the Aegean coast of Asia Minor mixed with a thriving maritime trade plied by Venetian merchants to precipitate a burgeoning slave market. Prisoners of war and victims of piracy were either made to wait upon the courts of the Turkish principalities or else shipped off westwards to serve middle-class Italian or Catalan (‘Latin’) households. The case of Iohannes Glafchyrno bears witness to how this pincer movement of Turkish and Latin expansion coalesced at the expense of the Greek-speaking population of the Aegean region.

The second person I would like to introduce you to was called Sophia Papadia. Sophia came from the island of Karpathos, which lies in between Crete and Rhodes. She came to Crete too, not as a slave, but as someone seeking financial help for ransoming captive family members. We know this because a priest called Ioannes Symeonakes, the most senior clergyman on Venetian Crete in his time, delivered a sermon on her behalf. A copy of this sermon, with a lot of its details unfortunately excised, was written down by Symeonakes in a manuscript that he finished in 1449, thereby supplying the latest possible date of the sermon. He admonished his congregation to follow the example of charity shown by Christ by giving alms to people held captive by so-called ‘heathen’ Muslims, including Papadia’s family.

In the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, a lot of Greeks started fleeing the ongoing Ottoman conquests of the Byzantine world and coming to places under Venetian rule, above all Crete. In the early fourteenth century, they had tended to go to another Mediterranean island ruled by Latins: Cyprus. Despite the fact that many Greeks were enslaved to the Venetians and the rest lived as second-class subjects, they nevertheless went there seeking a safer existence: the small Aegean islands, like Karpathos, had long been vulnerable to piracy, and the mainland of Greece was now falling piece-by-piece to invading Turkish armies. Understandably, however, some other Greeks chose to throw their lot in with the societies of the invaders instead. Greek-speaking clergymen played a key role in helping these refugees and captives, by writing letters and delivering sermons that asked fellow Christians to give what they could in charitable donations. Thus, as the Byzantine Empire retreated, it was often the Church that made up the social deficit.

Greek Captives and Mediterranean Slavery, 1260–1460 is a book about the thousands of Greeks taken captive by Latins and Turks in the later Middle Ages. It charts how the circumstances of conquest and commerce led to a diaspora of captives from the Aegean region all across the Mediterranean, from Cyprus to Catalonia. It asks what it was like to be captured and enslaved and how processes of redemption worked, and it considers how this crisis of captivity shaped relations between the different religious groups and political entities involved. In doing so, this book opens up a new social history of the late medieval Middle Sea, as viewed from the perspective of some of its most disenfranchised inhabitants.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the author

Alasdair Grant is postdoctoral Research Associate in the Emmy Noether Junior Research Group ‘Social Contexts of Rebellion in the Early Islamic Period’, Universität Hamburg.