…pacifist feminists have long argued we must

by Selina Gallo-Cruz

Content warning: mentions of rape and sexual harassment

Rape, war, racism, ecocide: a litany of violence. Are they comparable—and, if so, should they be compared? Across generations, feminist pacifists have not only replied with a resounding ‘yes,’ they have argued that comparing such acts is key to understanding the nature of power and violence. In order to grasp the operations of any of these situations—and to do something about them—they say, violence must be explored through these interconnections.

I’ve been lucky in my fieldwork to connect with such women—activists, scholars, community members—who have dedicated the better part of their lives to building nonviolent movements. And every time I have asked them about their gendered organizing experiences, they point to the importance of confronting sexual harassment, assault, and rape alongside the gendered nature of militarization and war, racism and colonialism, and ecocide.

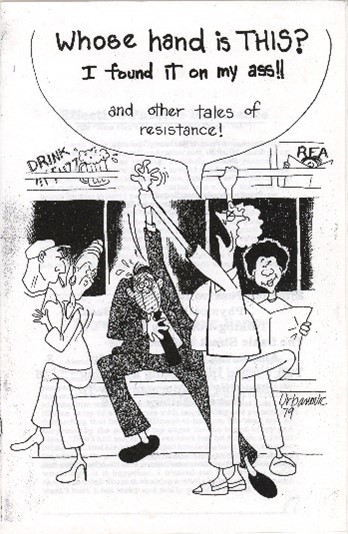

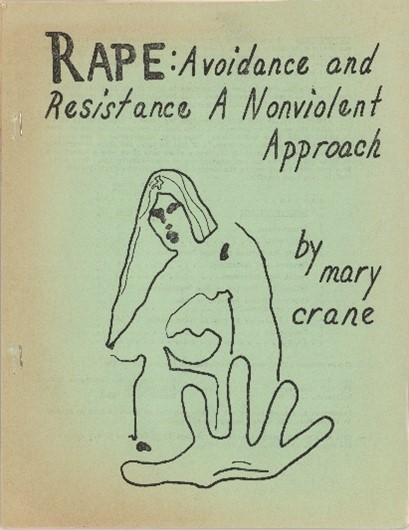

These women had not only held on to oral histories, they had also lovingly preserved stacks of impassioned writings on these topics, an archived mishmash of materials: professionally printed magazines, hand-typed and mimeographed newsletters, self-published essays or zines, each adorned with beautiful illustrations and provocative political art. As I began to dig deeper into peace and women’s movement archives and ask more pointed questions of the women I interviewed, a decades-long dialogue between feminists and pacifists on the meaning of nonviolence for women’s liberation unfolded. This is how my anthology Feminism, Violence, and Nonviolence emerged.

Exploring this archive allowed me to grasp the connections between rape, war, racism and ecocide that these women had identified, and to thematically center them around four insights into the intersectional social forces that coalesce in these tragic forms of violence. Forces that must be addressed if nonviolence is to be achieved.

Power

First: power. Power means different things to different people. But pacifist feminists argue that a new power politics is essential if women are to change the world. In her essay ‘Woman Power’, Charlotte Bunch, founder and longtime director of the Center for Women’s Global Leadership at Rutgers University, urges feminists to contest the traditional notion of power as ‘domination over others,’ a form of power too often concentrated in elite leadership and ‘star-systems’. Feminists must instead work towards collective empowerment and power-sharing, fostering every woman’s ability to cultivate her talents and capabilities, especially when taking on positions of representative leadership.

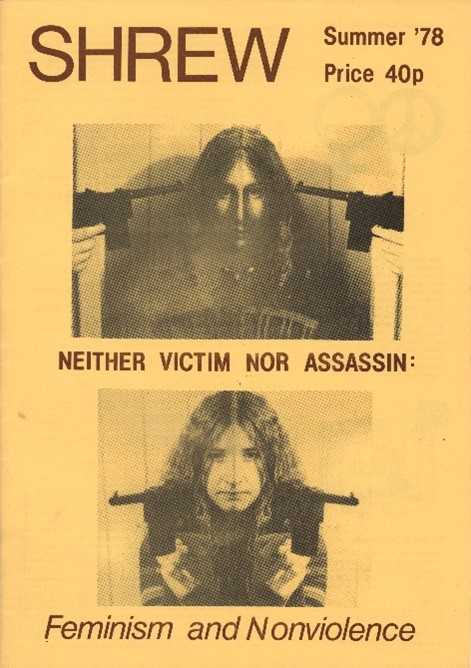

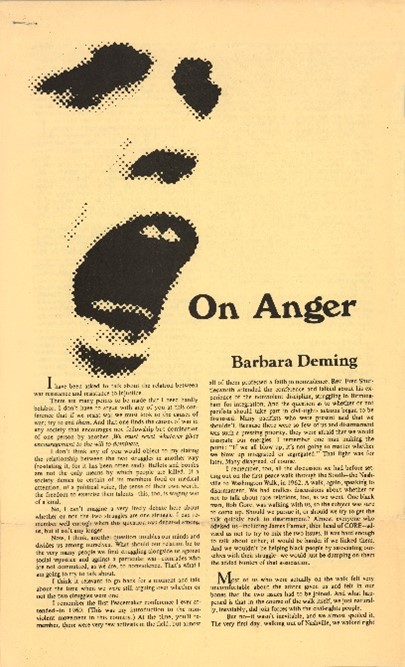

The Shrew was a collectively published activist magazine of the London Women’s Liberation workshop. This 1978 special issue explored the connections between feminism and nonviolence for rape, militarization, and nuclear power among other topics. Barbara Deming’s essay “On Anger” was published in 1971 WIN Magazine, the magazine of War Resisters League.

Anger

Second: anger. In conversation with the nonviolence movement, feminists resurrected their anger over injustice, staking a claim for deep indignation and a refusal to cooperate with those who would deny that defending their humanity as women should form a central organizing platform. Pacifist feminist Barbara Deming, a longtime activist in Civil Rights, anti-proliferation, environmental, women’s and gay liberation struggles, wrote about the pleas of her angry sisters:

There is indeed an essential and righteous anger that women can and should embrace in feminist movement that is not in itself violent—

Even when it raises its voice (which it sometimes does); and brings about agitation, confrontation (which it always does). It contains both respect for oneself and respect for the other. To oneself it says: ‘I must change— for I have been playing the part of the slave.’ To the other it says: ‘You must change—

For you have been playing the part of the tyrant.’ It contains the conviction that change is possible.

This anger was viscerally expressed in the rise of the women’s self-defense movement of the 1970s and 1980s, when women around the world began training in techniques to protect themselves from violent men both in the streets and in the home—a movement many essays in my forthcoming anthology eloquently and artfully document.

An impressive series of training manuals and collections of survivor stories were widely circulated among feminists committed to creating new spaces for women’s safety and self-defense, though women differed on the extent to which they could place their faith in nonviolence as a means of protection. Feminists like Mary Crane traveled the country teaching women strategies for rape resistance while others in separatist communities trained in the use of arms for their own personal safety.

Systems-analysis

Third: systems-analysis. Feminist pacifists found that a feminist-inspired systems-analysis added greater depth to their understanding of war and militarization. Comparing men’s experiences in military cultures to boys’ socialization in aggression and domination, their writings unpack an underlying system that idealizes male power controlling a lesser ‘Other’. Too often, this process is bound up in the objectification of women and feminized peoples, or in systems that make the violence on the other end of our consumption invisible.

Structural violence

Fourth: roots of structural violence. In dialogue with pacifists, feminists shed new light on the idea that we must address the structural violence of racism, colonialism, and ecocide at their foundations. As environmentalist and eco-feminist Vandana Shiva charges, these global systems of unabating extraction have railroaded over the wisdom of Third World women which centers on the inherent productivity of life and sustenance. In a world rife with compounding levels and forms of violence, intersectional work may seem daunting or even implausible. These lifelong organizers insist it is both necessary and the only effective way in which we might begin to change the world.

So, yes, these women argued, rape, war, racism and ecocide can and should be compared. Because to take on any of these acts means taking on all interrelated systems of Othering and domination that tie violence and human suffering together.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the author

Selina Gallo-Cruz is Associate Professor of Sociology at the Maxwell School for Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University. She is the author of Political Invisibility and Mobilization: Women against State Violence in Argentina, Yugoslavia, and Liberia and Have Repertoire, Will Travel: Nonviolence as Global Contentious Performance, co-editor of The Journal of Political Power, and Chair-elect of the American Sociological Association’s Peace, War, and Social Conflict section.

About the book

Get 30% off your copy with the code NEW30

Feminism, Violence and Nonviolence examines how feminists have engaged with nonviolence as a means of addressing violence from the 1970s to the 2000s. It features seminal essays, articles, pamphlets, flyers and excerpts from books of feminist thought by feminists and their allies, some of which are vitally important but difficult to find.