by Chris Murray

Should Europeans meditate? Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) said not, but William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) disagreed. To argue his opinion, each adopted Goethe’s character Faust as a paradigm for the non-Asian psyche.

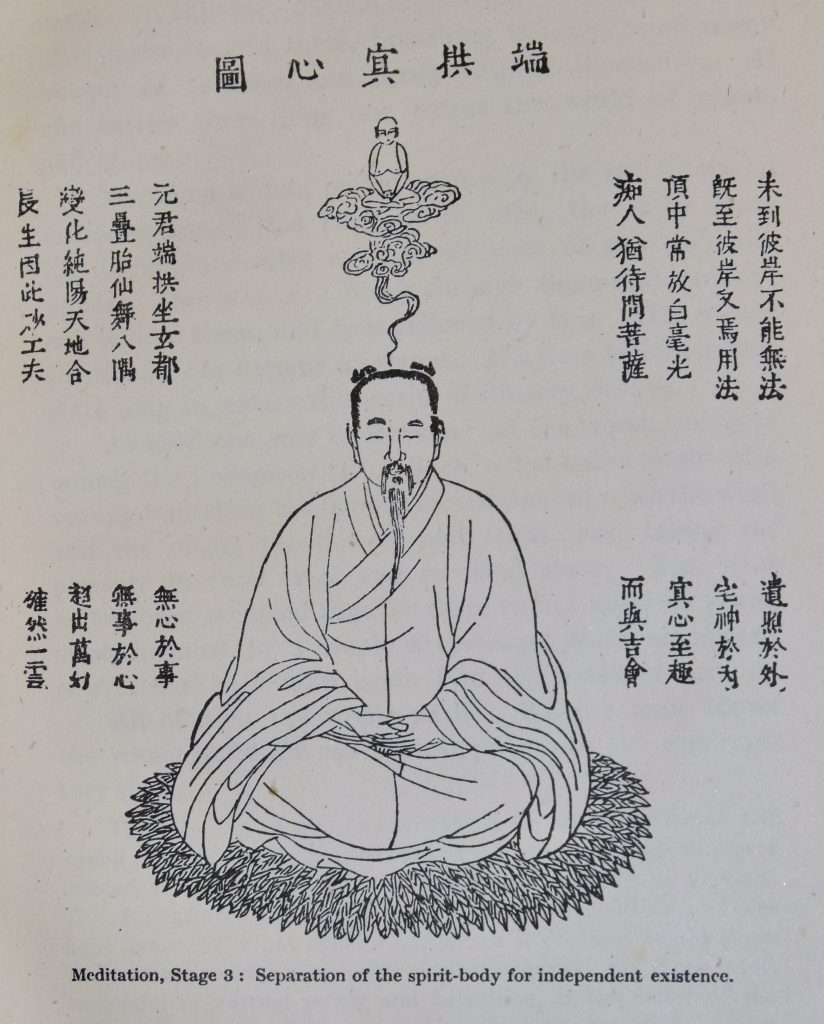

For much of his life, Yeats read about Asian spiritual traditions, but he couldn’t get the instruction he wanted in meditation. Unsurprisingly there were no yoga classes to be found in early twentieth-century Sligo, nor indeed Dublin or London. For that reason, Ireland’s greatest poet welcomed the 1931 English translation of The Secret of the Golden Flower, a Daoist manual translated from Chinese, accompanied by Jung’s commentary. The book told the readers exactly how to meditate, although Jung implored them not to: Jung said that the European mind was fundamentally divided in a way he likened to Faust. Hence, Jung said that for Europeans to meditate could only induce insanity.

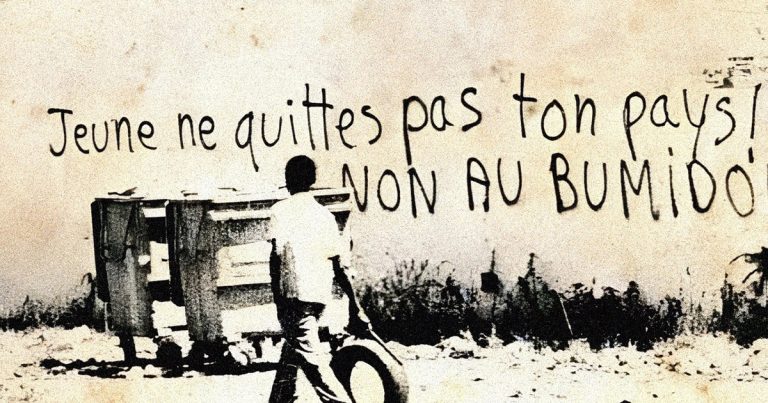

Yeats responded to Jung when he was asked to introduce a new translation of Patanjali’s Aphorisms of Yoga, published in 1938. Here Yeats used the example of Faust to opposite effect: Yeats said that meditative Enlightenment is the same as the elusive ‘moment’ that Faust would wish to prolong in his wager with the demon Mephistopheles. Furthermore, Yeats drew on various unfashionable ethnographic-accounts to argue that the Irish were Asian, not European, meaning that Jung’s restrictions shouldn’t apply to the Irish.

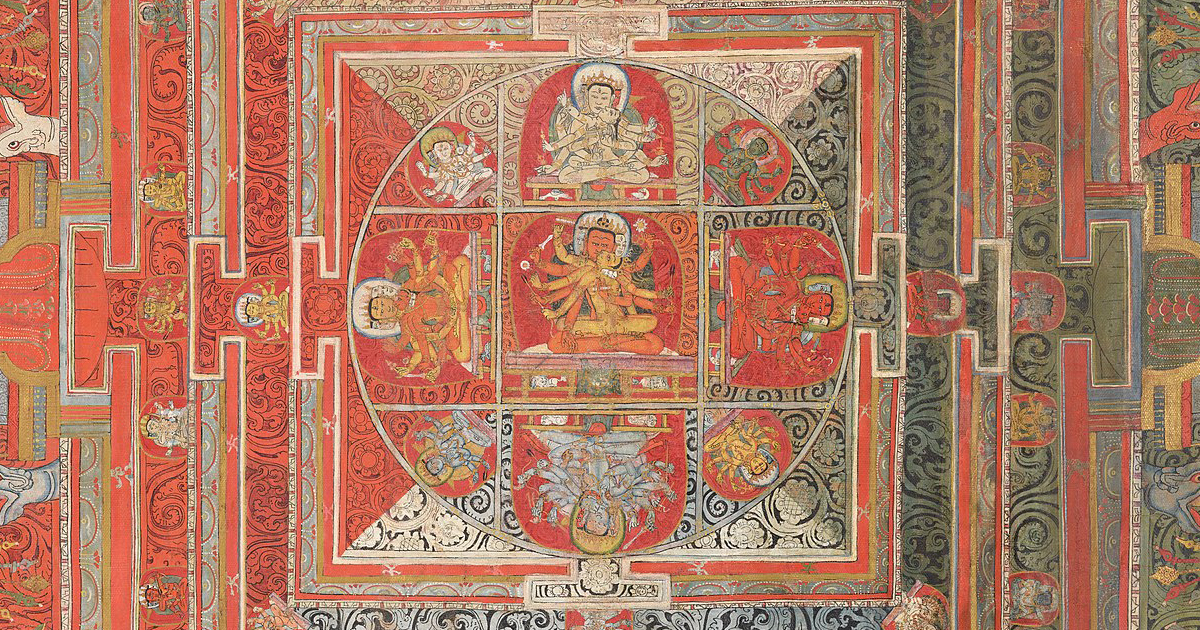

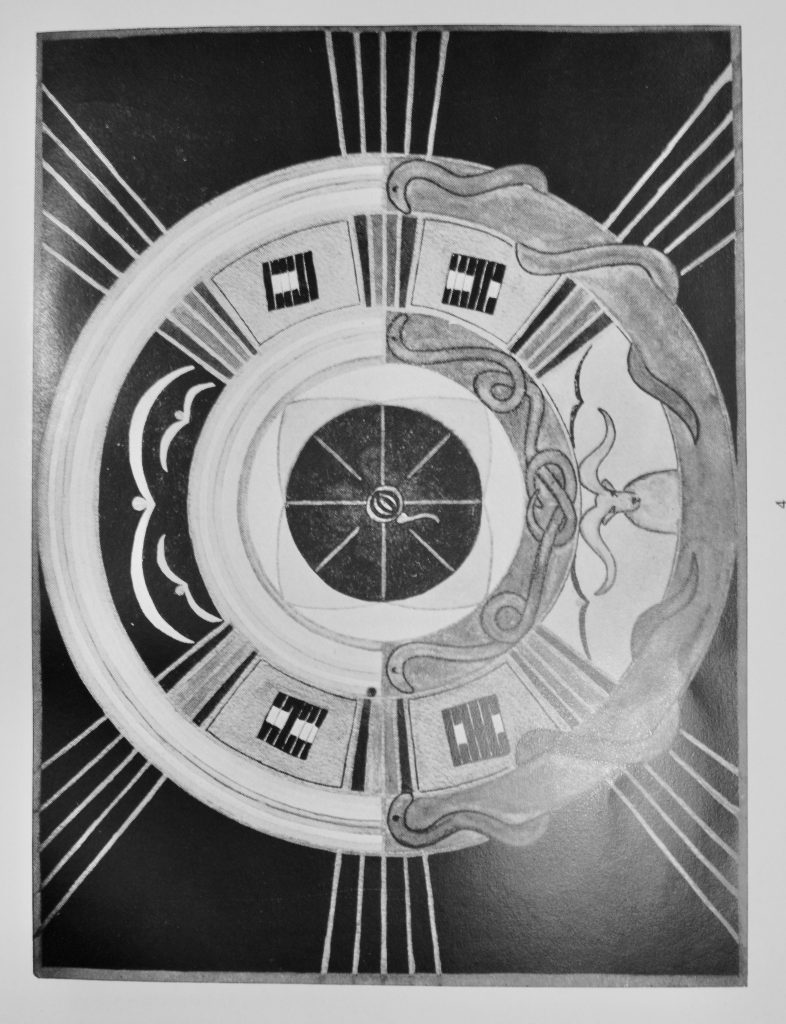

Yeats hoped that the individual project of Enlightenment could be recreated at a collective level: late poems such as ‘The Statues’, and reflections on his political career, are inflected by a wish that the lessons of meditation could lead Ireland to realise its national destiny. Yeats felt that he didn’t accomplish this grand, political vision. But at least he got to try out meditation techniques for himself. For his part, Jung was evidently excited by meditative traditions, despite his caution, as we can see from the mandalas he painted in response.

The reception of these translated meditation-manuals shows us how these writers’ interests in Asia not only included reading, but lived experience: meditating, in Yeats’s case, and painting in Jung’s. The publications also represent a key phase in Western knowledge of Asian meditation-practices, and the transmission of ideas that would lead to the recreational forms of yoga and Daoist self-cultivation we know today.

Images in this blog are provided courtesy of the Matheson Library.

Read the full essay in IUR 53.2 here

About the author

Chris Murray (FRAS) is Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. With interdisciplinary interests in global, transcultural exchange, his writing includes the books China from the Ruins of Athens and Rome: Classics, Sinology, and Romanticism (2020), Tragic Coleridge (2013), and a memoir, Crippled Immortals (2018).

About the journal

The Irish University Review was founded in 1970 at University College Dublin as a journal of Irish literary criticism. Since then, it has become the leading global journal of Irish literary studies.

The journal has no prescriptive agenda about the subject or methodology of the literary criticism it publishes, other than insisting upon the highest standards of academic scholarship through a rigorous screening and peer review process. It welcomes submissions on all aspects of Irish literature in the English language, particularly submissions which expand the range of authors and texts to receive critical treatment, and which challenge the prevailing trends and assumptions of the field.