by Jason Read

One of Marx’s most lasting contributions to critical thinking about capitalism and society is the concept of the alienation of work and life under capitalism. Despite being associated with his critique of capitalism, it was principally developed in his notebooks as he was first developing his criticism of political economy. These notebooks were posthumously published as The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. This fragmentary and provisional development has resulted in so much of the criticism of the concept of alienation. What does it mean to be alienated? What is one alienated from? And, more importantly, what would it mean to not be alienated? Franck Fischbach offers an answer to these questions, by reading Marx and Spinoza together.

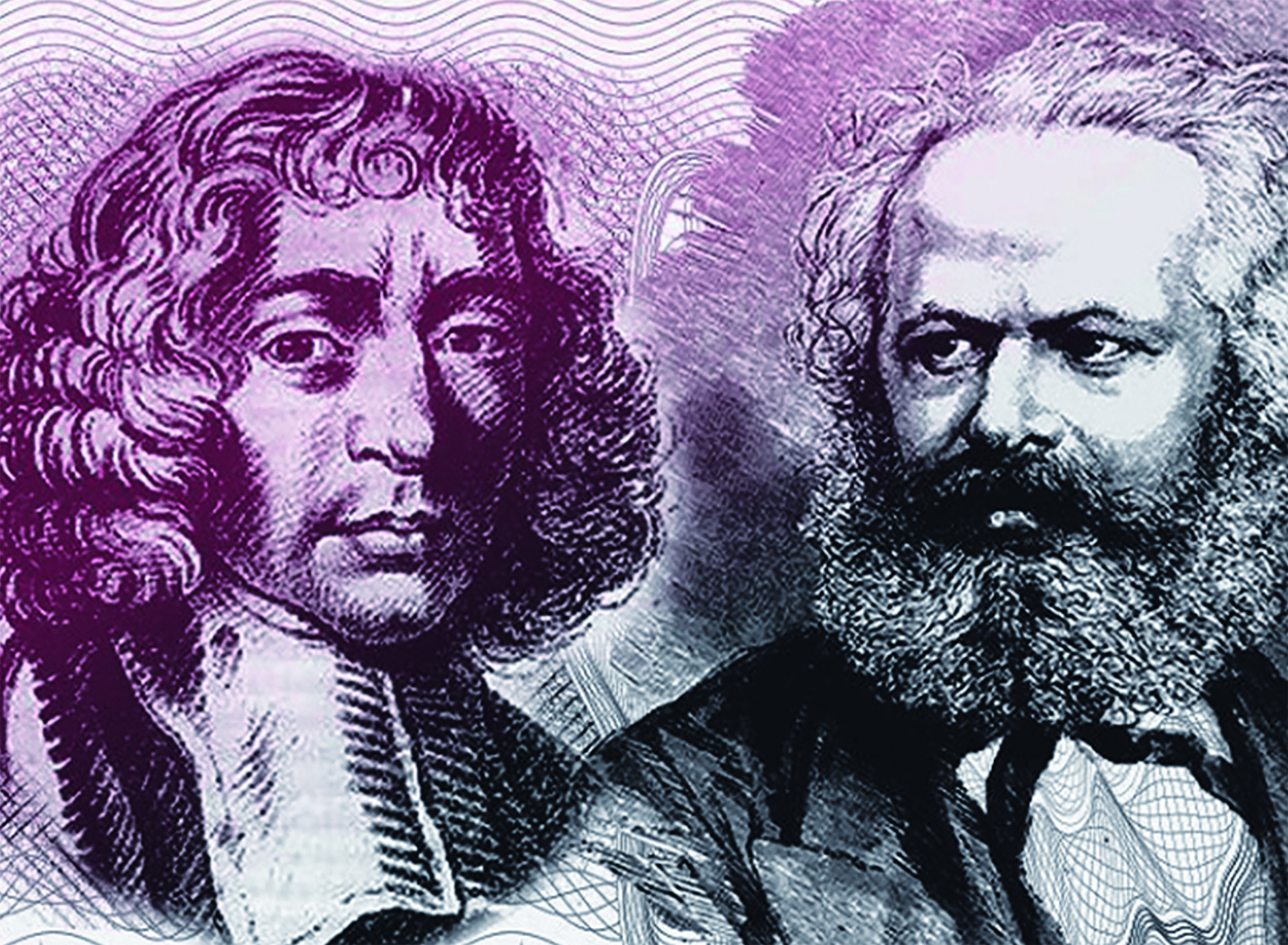

Spinoza casts philosophical light on Marx

Fischbach takes a surprising detour through Spinoza, arguing that Spinoza is necessary to bring out the philosophical commitments that are immanent to and concealed within Marx’s critique of political economy. Spinoza casts philosophical light on Marx.

The first thing this light reveals is that Marx and Spinoza share a similar set of philosophical commitments. These commitments begin with a fact of life that would seem so simple if so many philosophers did not overlook it: that human beings are, first and foremost, natural beings with bodies, needs and desires. That we are, to combine the formulations of Marx and Spinoza, part of nature. We are not, as many philosophers claim, ‘kingdoms within a kingdom’. We are not fundamentally different things governed by different rules than the rest of the natural world.

From this perspective, alienation cannot be the loss of subjectivity in an object, as it is often claimed. Objectivity, a connection to the objects of the natural world, is our natural condition. We cannot understanding alienation as a loss of subjectivity in an object, in labor that loses itself in the production of commodities. Alienation is the loss of objectivity, the loss of a world. According to Marx, the defining characteristic of capitalism is that workers do not own the means of production, or the land, tools or instruments that are put to work. They are dependent on the capitalist for the very condition of their livelihood.

Alienation: the loss of an object by a subject

The constitution of the worker as someone who has only their labor power to sell is also reduced to a subject. As Fischbach argues:

The reduction of human beings, by this abstraction, from natural and living beings to the state of ‘subjects’ as owners of a socially average labour power indicates at the same time the completion of their reduction to a radical state of impotence: for the individual to be conceived and to conceive of itself as a subject it is necessary that it see itself withdrawn and subtracted from the objective conditions of its natural activity; in other words, it is necessary that ‘the real conditions of living labour’ (the material worked on, the instruments of labour and the means of subsistence which ‘fan the flames of the power of living labour’) become “autonomous and alien existences.”.

Marx with Spinoza, page 88

This is a fundamental reversal of what is commonly understood by alienation. Alienation is not the loss of the subject in an object. It is not the externalization of one’s activity and power in a commodity that is owned by another. Alienation is the loss of an object by a subject. It is the reduction of a human being to purely the capacity of labor power without the means to realize this power. In other words, the culmination of alienation is not so much working for someone else, making someone else rich. It is unemployment, being reduced to a pure potential, a capacity to work, with no possibility for actualizing it.

The contemporary relevance of Marx and Spinoza

Framed in such a way, the contemporary relevance for Fischbach’s reading of Marx in light of Spinoza is clear. This contemporary relevance is not limited to the way in which this concept of alienation fits with a contemporary era of capitalism in which unemployment, underemployment and precarity are more defining characteristics of contemporary work than the utter exhaustion and loss of self of the 19th-century working conditions Marx described. Our era is one of individual subjectivity. We are encouraged to see our lack of connection to the world and others as the condition of our freedom.

What Fischbach demonstrates in reading Marx through Spinoza is that this individual, this kingdom within a kingdom, is not the condition of our freedom but the basis of our subjection. What we lack is not individual freedom. We lack connections: connections with the world and others, that make it possible for us to actualize our capacities.

About the book

Marx with Spinoza: Production, Alienation, History is a provocative study of the intersection of Marx and Spinoza that shows how their respective philosophies engage overlapping questions and problems.

Get 30% off your copy with discount code NEW30

About the author

Jason Read is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Southern Maine. He is the author of The Micro-Politics of Capital: Marx and the Prehistory of the Present (SUNY 2003) and The Politics of Transindividuality (Brill 2015/Haymarket 2016) and a collection of essays, The Production of Subjectivity: Between Marxism and Philosophy (Brill 2022/Haymarket 2023). He is the translator of Franck Fischbach’s La Production des Hommes: Marx avec Spinoza (published as Marx with Spinoza: Production, Alienation, History by Edinburgh University Press in 2023). He also has a book The Double Shift: Marx and Spinoza on the Politics and Ideology of Work coming out in 2024 from Verso. He blogs on popular culture, philosophy and politics at unemployednegativity.com

Alienation is the separation of value from the one who produced the value. Workers use their productive capacity (labor power) to produce something that has more value than the sum of values contained in the thing. Thousands of workers assemble thousands of values into a commodity called a car. When the car comes off the assembly line it is not owned by the workers who produced it. But, yet it has an objective real value measured by market forces. That value is sometimes erroneously called the MSRP. The car must then be sold, on average, for at least its true market value. Where does the extra (surplus) value come from? It comes from the collective (unpaid) labor of the workers.

Workers are only paid the value of their potential labor which is hourly wages. The difference between the unpaid labor contained in the car and the selling price of the car is profit, which value is taken, extracted, alienated from the workers who produced it. And it wasn’t Marx who discovered the unpaid labor which is the basis of profit. It had already been discovered by Adam Smith, David Ricardo and other18th century economists.