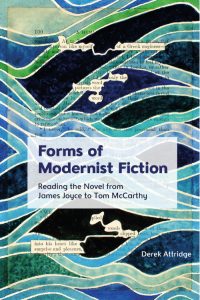

by Derek Attridge

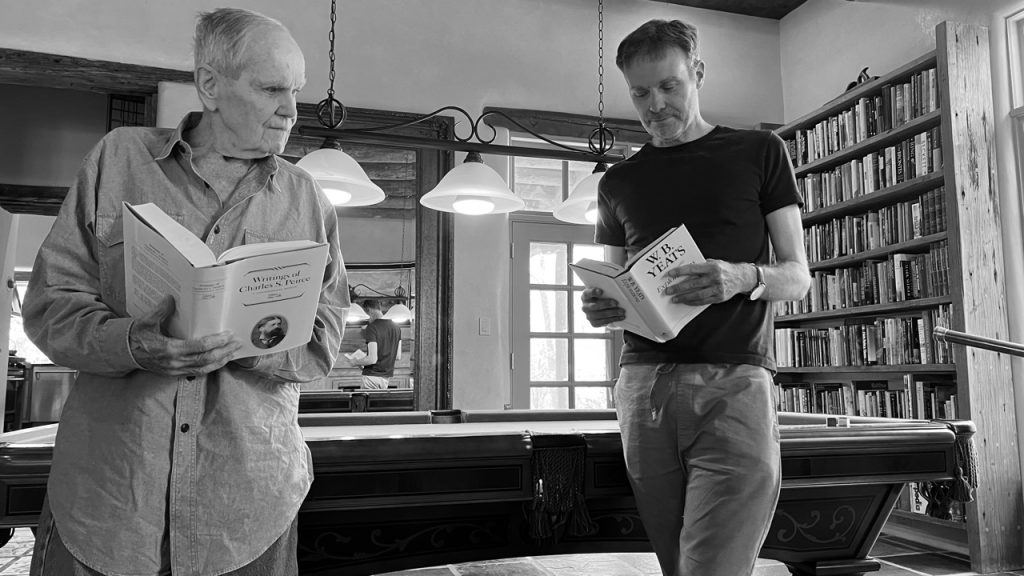

There are two names in the subtitle of my book Forms of Modern Fiction: Reading the Novel from James Joyce to Tom McCarthy. One of these is less well-known than the other; in fact, for many readers, especially in the United States, there might be a moment of confusion. ‘Isn’t McCarthy’s first name Cormac?’, an aficionado of American fiction might well ask. Cormac McCarthy, who died recently, was one of the most distinctive and powerful of American novelists, author of such famous novels as All the Pretty Horses, No Country for Old Men, and The Road, all made into successful films. However, the McCarthy I write about is English, and very much alive. His novels Remainder, Men in Space, Satin Island, and The Making of Incarnation have brought him a reputation as one of the most original of current British writers.

My book is an exploration of some of the authors around the world who, in my view, have honoured the legacy of Joyce through their innovative writing. I am especially interested in the experience of the reader in encountering these challenging works: the word ‘novel’ in my subtitle, ‘reading the novel’, has a double meaning. (One of my examples, in fact, is a play—a highly novel one, of course.) Why did I choose to include Tom, not Cormac, McCarthy?

Cormac McCarthy’s debt to Joyce is undeniable. I could have devoted a chapter to Suttree, a sprawling chronicle of the seamy side of one city, Knoxville in 1951, told largely through the activities and thoughts of a single character. The parallel with Leopold Bloom’s Dublin in 1904 is obvious. Then there’s McCarthy’s style: its baroque extravagances are also unquestionably Joycean.

As a taste of the two styles, here first is a moment in the phantasmagorical ‘Circe’ episode of Ulysses. Bloom is being harangued by ‘THE SINS OF THE PAST’:

By word and deed he frankly encouraged a nocturnal strumpet to deposit fecal and other matter in an unsanitary outhouse attached to empty premises. In five public conveniences he wrote pencilled messages offering his nuptial partner to all strongmembered males. And by the offensively smelling vitriol works did he not pass night after night by loving courting couples to see if and what and how much he could see? Did he not lie in bed, the gross boar, gloating over a nauseous fragment of well used toilet paper presented to him by a nasty harlot, stimulated by gingerbread and a postal order?

And here’s another accusation – also made by a hallucinatory character – against Cormac McCarthy’s hero:

Mr Suttree it is our understanding that at curfew rightly decreed by law and in that hour wherein night draws to its proper close and the new day commences and contrary to conduct befitting a person of your station you betook yourself to various low places within the shire of McAnally and there did squander several ensuing years in the company of thieves, derelicts, miscreants, pariahs, poltroons, spalpeens, curmudgeons, clotpolls, murderers, gamblers, bawds, whores, trulls, brigands, topers, tosspots, sots and archsots, lobcocks, smellsmocks, runagates, rakes, and other assorted and felonious debauchees.

Not surprisingly, the surviving notes for Suttree reveal the importance of Joyce’s work for McCarthy: he writes ‘Je crois c’est trop Joycean’ (I think it’s too Joycean) and quotes an appropriate phrase from Ulysses: ‘“A hoary pandemonium of ills.” JJ 555.’

Tom McCarthy, too, acknowledges the importance of Joyce. His collection of essays, Typewriters, Bombs, Jellyfish, includes an essay with the title ‘Why Ulysses Matters’. But his allegiance to Joyce is not displayed in the same way. He does write extraordinary prose, but instead of heightening the visceral impact of the language with richly evocative vocabulary he often empties it of emotion. The reader is invited to take pleasure in the sheer matter of the world, its curious forms and unexpected relationships. Here’s part of a paragraph from The Making of Incarnation describing a bobsleigh in a wind-tunnel:

On the central monitor the bobsleigh’s silhouette crouches in vivid blue, innermost doll of a matryoshka set, with ever-larger silhouettes repeating all around it and each other, grading from green to yellow as they multiply. No fixed shells, though, these dolls are living – or maybe dying. Their bodies, as they tumble escalating outwards, are forever breaking open, pixel life-blood gushing from one level to the next, which ruptures too, ditto the next layer – on and on up, in lurid flows that radiate towards some vague periphery, then, when it seems all form and structure must have ebbed away, turn round and radiate back in again, the two-way current generating in its midst small, transitory islands, intermediate thresholds that, no sooner than they’re formed, start bleeding too.

Tom McCarthy’s writing teems with descriptions, both fascinating and repellent, of the multifarious materials that make up our world. While Cormac McCarthy invokes an old tradition of intense feeling evoked by richly-laden vocabulary, Tom McCarthy invents a new way of writing appropriate to the conditions we live in today. To my mind, this makes him the more Joycean of the two.

About the book

Get 30% off with discount code NEW30

Innovative literary form examined from the point of view of the reader’s experience

Focusing on the experience of the reader in engaging with a selection of these works from around the globe, Forms of Modernist Fiction argues that a rigorous attention to formal features is crucial in appreciating their achievement and in understanding the impact of the early modernists on the history of the novel.

Don’t forget to sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases!

About the author

Derek Attridge is the author or editor of thirty books on modern fiction, literary theory, the history and forms of poetry, and South African literature. He is Emeritus Professor at the University of York, U.K., and a Fellow of the British Academy.