by Cathryn Spence and Cordelia Beattie

The saying goes, ‘Clothes make the man’, but in early modern Scotland, many women would have considered clothing to be a central part of their identity. According to early modern legal treatises, married women could only make a will with their husband’s permission and even then they could only give away their own personal property, such as clothing and jewellery. While our research found that married women frequently made wills of their half or a third (if they had children) of the household’s goods, clothing was often treated as a key item to be reallocated.

Our project examined testamentary material (wills, inventories, etc.) pertaining to women, particularly married women, in Scotland in the sixteenth century. These documents – which are available to view on ScotlandsPeople – typically contain an introductory preamble, an inventory of the deceased person’s goods, and two sections relating to debts – debts owed by the testator and debts owed to the testator. Following these sections, a statement of the value of the testator’s estate is made, and a statement of whether the estate is to be divided into parts, depending on whether the deceased had a living spouse or children. Many of these documents are known as testaments testamentar, meaning they include a last will (or legacy) in which the testator bequeaths his or her goods.

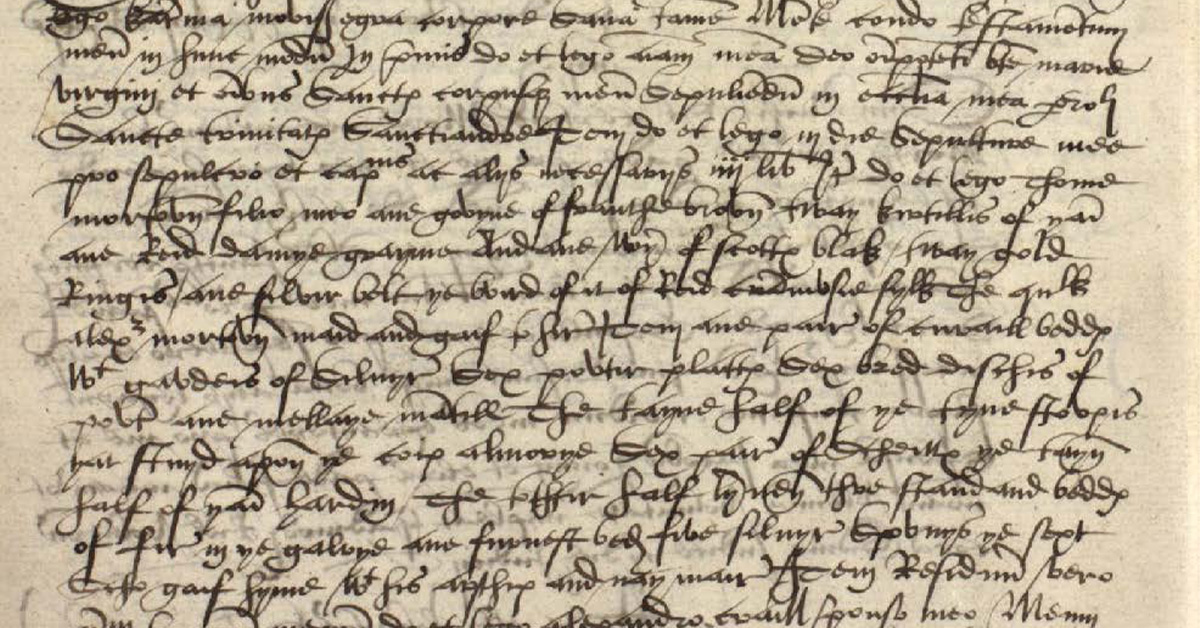

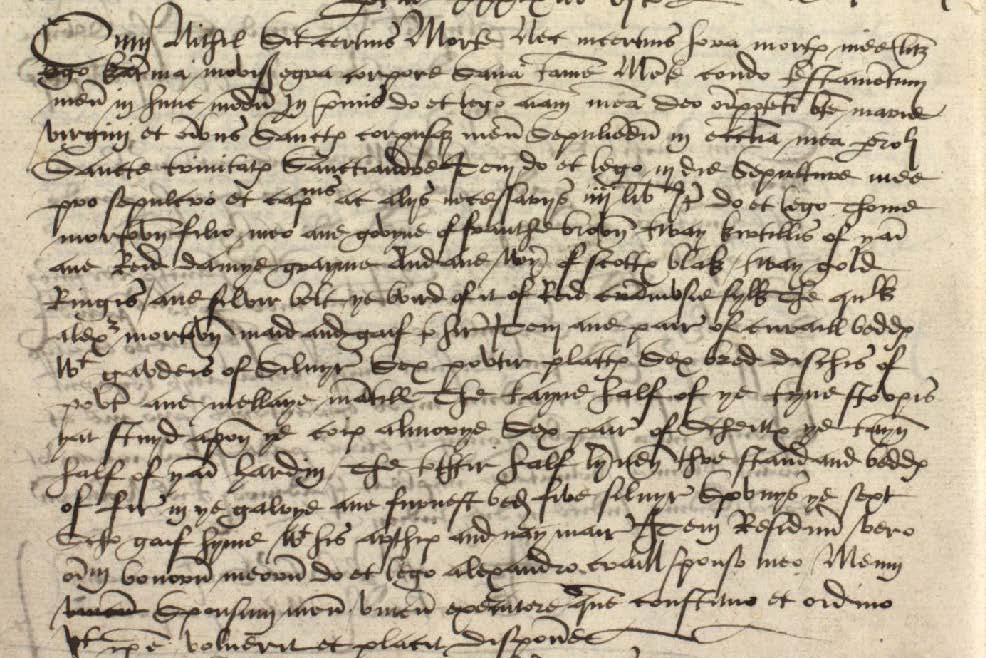

One of the items most commonly bequeathed in the legacies we read was clothing – and this could be quite extensive and expensive. Consider an entry in the will of Katherine Moviss, the wife of Alexander Craill, which was made on 21 May 1549 in St Andrews. In her legacy, recorded in Latin, Katherine gave her son, Thomas Morton:

‘A gown of French brown, two tunics of same, one red demi-grain and another of Scots black, two gold rings, one silver belt the border of it of red crimson silk, the which Alexander Moretoun made and gave to her’.

Given that Katherine’s son is named Thomas Morton, and her husband is identified as Alexander Craill, it is likely that Thomas was Katherine’s son from an earlier marriage, presumably to the Alexander Morton who made and gave her the belt, if not all the clothes.

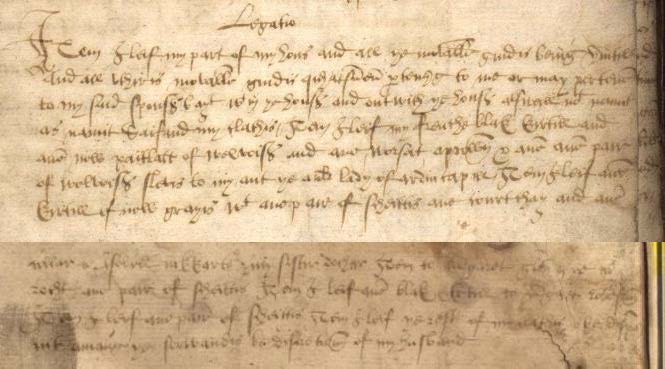

Katherine Dowglass (or Douglas), another Katherine living in sixteenth-century Scotland, also dispensed a significant amount of clothing in her legacy. In this document, recorded on 9 February 1563 in Dumbarton, Katherine noted:

‘I leave my part of the house and all the moveable goods being there until and all other moveable goods whatsoever pertaining to me both within the house and outwith the house as well as anything not named as named saving my clothes.’

Indeed, Katherine Dowglass was very particular about which clothes should be left to whom. She further stipulated:

‘I leave my French black gown and one new garment worn over the neck and upper part of the chest of velvet and one worsted wool apron and one pair of velvet sleeves to my aunt the old lady of Ardincaple; I leave a gown of new gray cloth with a pair of sheets one kerchief and one collar to Issobell MkKartor, my sister’s daughter; to Margaret Glen one pair of sheets; I leave one black gown to Margret Robeson; I leave the rest of my clothes to be disponed among the servants by the discretion of my husband.’

Clothing was important to the women of sixteenth-century Scotland. It was often valuable and cherished, used and reused. Furthermore, the act of bequeathing such clothing was important – materially, symbolically, and legally. Materially, such bequests underline the worth of clothing and the value of such items of material culture in the premodern period. These were long-lasting items that could be used by multiple generations, in a period in which people typically owned few personal items. Symbolically, these bequests helped the testator affirm her ownership and control of these items, and it was also key in preserving her memory with those who received them.

Legally, the records of these bequests help historians understand the position of women in this period, including the items and activities they controlled, and how laws governing the control and dispersal of property worked in late medieval and early modern Scotland. What is certain from these testaments, and evidence like the control and bequests of items of clothing described above, is that married women could be active and engaged members in the end-of-life process of will writing.

What do your clothes mean to you?

About the journal

The Scottish Historical Review is the premier journal in the field of Scottish historical studies, covering all periods of Scottish history from the early to the modern, encouraging a variety of historical approaches, with articles written by leading scholars and Scottish historians.

Sign up for TOC alerts, subscribe to SHR, recommend to your library, and learn how to submit your paper.

About the author

Cathryn Spence is Assistant Professor in History at the University of Guelph.

Cordelia Beattie is Professor of Women’s and Gender History at the University of Edinburgh.

They worked on this project, in partnership with the National Records of Scotland.