by Maria Flood and Michael C. Frank

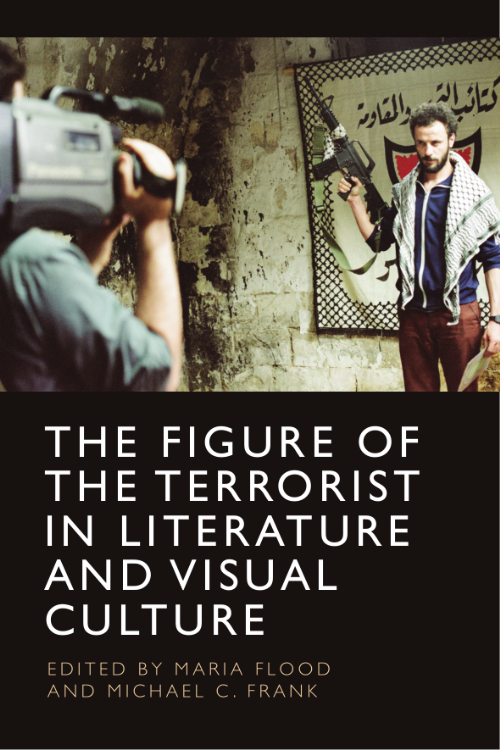

The Figure of the Terrorist in Literature and Visual Culture editors Maria Flood and Michael C. Frank discuss what inspired their research for their new book and how the discourse around terrorism has developed in recent years.

Tell us a bit about your book

Michael: Even though terrorism is such a widely discussed phenomenon, we tend to know surprisingly little about those who join extremist organisations and agree to become involved in political violence – let alone the circumstances that drove them to do so. According to scholars like the sociologist Ghassan Hage, this is not a coincidence: there is a veritable ‘fear of explanation’ when it comes to terrorism, as it is much easier – and politically more opportune – to outright condemn such acts. Against this background, we ask: How do cultural representations of terrorists relate to the ‘condemnation imperative’ diagnosed by Hage, and what other factors have a bearing on how we perceive and feel towards such characters?

Maria: Michael and I began this project with a conference in Zurich in November 2019, just before the pandemic, which was a really exceptional event. One of our goals was to question, overturn or enrich some of the established paradigms of terrorism studies in the humanities. In the resulting book, we have tried to feature topics as diverse as the representation of IRA terrorists in superhero comics, football hooliganism, Burmese literature, female radicalisation, white nationalism in French cinema.

What inspired you to research this area?

Maria: I think the moment I became interested in terrorism, and perhaps audio-visual media, was 9/11. I still clearly remember watching the images of the Twin Towers on repeat in my living room in Ireland.

Michael: The same is true for me. While remaining glued to my television set for days, I realised I was witnessing history in the making, and this was the first time I became fully aware of the power of framing. What I saw on CNN was not a simple representation, but an interpretation of the events, and I remember being irritated by captions like ‘America Under Attack’ and President George W. Bush’s almost instantaneous declaration of a ‘war against terrorism’, even before there was any certainty about the perpetrators and their intentions. The attacks could have been framed as a politically motivated crime to be prosecuted by international tribunals; instead, they were interpreted as an irrational act of ‘evil’ (Bush) and within days, they became the beginning of ‘America’s New War’ (CNN). As a literary scholar, I felt that it was my responsibility to contribute to a critical examination of this narrative, and to interrogate the public discourse that enabled the ‘War on Terror’.

Maria: Growing up in the Republic of Ireland in the 1990s, we didn’t have to think about terrorist attacks directly, but before the Good Friday agreement, I remember crossing the militarised zone in Newry, and hearing the sounds of helicopters and explosions at night. I’ll also never forget driving through a Loyalist estate and seeing a mural that depicted St. Patrick, our cosy national emblem, being impaled. It seemed so strange to me that we could live lives of such peace mere miles from a place that seemed riven with conflict – how you can be a perfectly assimilated citizen in one country, and then drive for half an hour and become an ‘enemy’.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

Maria: I suppose the most exciting moment for me at the Zurich conference was during a screening of Talal Derki’s ‘Of Fathers and Sons’ (2017), a disturbing documentary in which the director embeds himself with an ISIS family in Syria, pretending to be an extremist himself. It makes for extremely uncomfortable and difficult viewing, as the film combines beautifully shot sequences of the children and their lives with the horror of extremist beliefs and violence. After the screening, a lively and heated debate broke out among some of the attendees, regarding, precisely, the film’s truthfulness, and its potential to incite Islamophobia on the one hand, and to serve as propaganda on the other.

Michael: Yes, I often think back to that screening – and the silence that followed it.

Maria: It was a tense moment, but one that reminded me of the power of art to incite discussion and generate ambiguity about a topic that too often generates to oversimplification.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

Maria: The most surprising part of my own research for this book was while working on Deeyah Khan’s documentary, ‘White Right: Meeting the Enemy’. I watched this film when it first appeared in 2017, and when I returned to the research in 2020, I was astonished to discover that the film itself, and the filmmaker’s encounters with a number of white radicals in the US, had actually led to many of them leaving the movement, notably Jeff Schoep and Ken Parker. I was astonished that these results emerged from Khan’s work.

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

Michael: Reading the contributions to our volume brought home to me how much terrorism and its surrounding discourse have developed in recent years. From groups of foreign extremists such as Mohammed Atta’s Hamburg cell, we have moved, first, to homegrown terrorism inspired by al-Qaeda and, then, the radicalisation and recruitment of second-generation Muslim immigrants and converts by the Islamic State. In a parallel development, the rise of white supremacy and right-wing violence have prompted Western governments to reconsider their rather selective deployment of the word ‘terrorism’, which used to be reserved for militant Islamists. ‘Terrorism’ is never just one thing, and this becomes even more obvious when we look beyond the Western context or the post-9/11 era, as many of our contributors do.

Maria: The main thing I became aware of was the astonishingly similar patterns emerging in the ideological construction of the figure of the terrorist across time periods, cultural contexts and artistic media – the desire, or perhaps the need, for dominant discourses to ‘other’ the terrorist recurs again and again, even in texts that explicitly seek to counter this imagery. Essentially, it is extremely difficult to see beyond the violence of the terrorist.

About the book

Get 30% off with discount code NEW30

The first volume to approach the tabooing of terrorists from an interdisciplinary and comparative perspective

About the editors

Maria Flood is Senior Lecturer in World Cinema at the University of Liverpool.

Michael C. Frank is Professor of Literatures in English of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries at the University of Zurich