by Megan Nutzman

Imagine, if you will, a woman living in Caesarea in the early fourth century CE. Caesarea is a bustling metropolis, the provincial capital. It is home to a cross section of Palestine’s inhabitants: Roman officials, Greek-speaking polytheists, Jews, Samaritans, and Christians. This woman has a young son who regularly gets sick. One day he will be shivering uncontrollably, and the next his body will be consumed with fever. Bad headaches and vomiting complicate the child’s situation. The woman’s husband is a skilled artisan, and so they have a little money to spend on physicians, but none of the prescribed remedies have had any lasting effect. He seems to get better, only to have the symptoms return with a vengeance sometime later. Our mother is desperate. She fears that her son does not have the strength to survive another episode. Only divine intervention will save him.

This woman’s son has malaria, a disease that was endemic throughout the region. Illnesses and injuries of all sorts were ubiquitous in the ancient Mediterranean world. Manual labor resulted in traumatic injuries. Poor hygiene and sanitation led to outbreaks, and contagious diseases spread rapidly. Put simply, physical infirmities of one sort or another were inescapable. The same impulse that drives people to the Internet today to research symptoms and find possible treatments would have also motivated those in the ancient world to look for answers. Casual conversations at wells, along roads, and in markets would have inevitably turned to the health and well-being of one’s family. One woman might be tired because she had been up all night caring for an elderly relative, while another might question a friend as to why they had not seen a particular neighbor recently. And we can imagine that our woman from Caesarea would talk about little but her fears for her ailing son. In each of these situations, responses would have contained a mixture of sympathy and advice: Have you tried this herb? My cousin visited a holy man who cured him. Did you hear about my brother’s son who was healed after wearing an amulet? I know a poultice that will work. You should bathe in the hot springs. In a world where disease and death were omnipresent, these conversations would have been common.

To which of Caesarea’s diverse communities does our woman belong? I would suggest that it does not matter. In Roman and late antique Palestine, these exchanges crossed the notional lines that divided Greeks from Romans, Jews from Christians, and Samaritans from the followers of local deities. The inevitability of sickness and injury would have made people willing to experiment with seemingly beneficial forms of healing, even if they originated in a foreign cultural or religious tradition. Within circumstances of close cultural contacts such as prevailed in cities like Caesarea, the setting was ripe for neighbors to borrow rituals perceived to be efficacious and to alter them to fit their own cultic framework. As a result, they all employed related means of seeking miraculous cures.

Our modern scholarly conventions for studying ritual healing, divided into categories of “religion” and “magic,” fail to capture the full range of ritual options that this mother had available to her. While ideological concerns may have informed the decisions of our mother from Caesarea, I would suggest that other considerations such as cost, proximity, and reputation would have had as much, if not more, influence. Hearing of the ritual words that a neighbor spoke daily over a sick child who later recovered, our mother might have given them a try, regardless of whether these prayers, hymns, or psalms originated within her own community, or even if she understood the words she was saying. Another option would be to bring her son to a church and ask someone to pray for him and anoint him with oil. While we would typically think of this as an option restricted to Christians, a successful cure of this sort might actually motivate a person to convert to Christianity. If the family still has a bit of money, she could pay a ritual practitioner to exorcise the demon that is causing the illness or purchase an amulet to protect him from future attacks. The practitioner might have a supply of ready-made, generic amulets for sale, or the mother might commission one that named both her son and herself and that specified the fevers and chills from which he suffered. With the ability to travel, she could seek out a holy man, perhaps a monk in the desert with a reputation for cures, or she could travel to a sacred site in expectation of a healing theophany. The cheaper options, and those nearer to home, would have likely been the ones she tried first. Only when those failed would she venture further afield.

Throughout all of this, our mother’s underlying concern would be to find a cure for her son. Faced with the thought of losing him, she would do whatever it took to keep him from getting sick again. Even if she was aware that religious elites forbade her from pursuing certain cures, her desperation would have led her to try anything. In her mind, it was better that her son live through these rituals, than that he die without them. The availability and attractiveness of cures to women such as this is precisely why religious elites felt compelled to police the ideological border that separated permissible cures from the forbidden ones of neighboring groups.

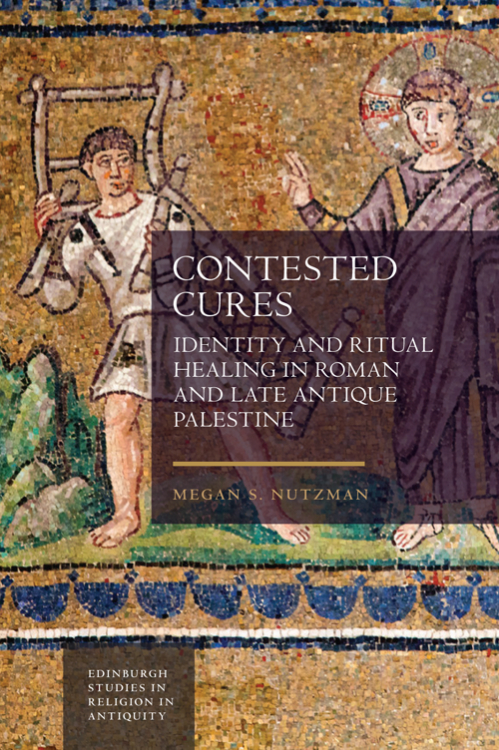

The original unedited version of this excerpt appears in Contested Cures by Megan Nutzman.

About the book

Studies the people, places and objects credited with ritual cures and the elite rhetoric critical of these cures

This innovative study synthesises evidence for the full range of healing rituals that were practised in the ancient Mediterranean world. Examining both literary and archaeological evidence, it considers ritual healing as a component of identity formation and deconstructs the artificial boundary between ‘magic’ and ‘religion’ in relation to ritual cures.

About the author

Megan Nutzman is Assistant Professor of History at Old Dominion University, USA. She is the author of a number of journal articles including in Jewish Studies Quarterly and Greek Roman and Byzantine Studies. This is her first book, based on her PhD, which she achieved in 2014.