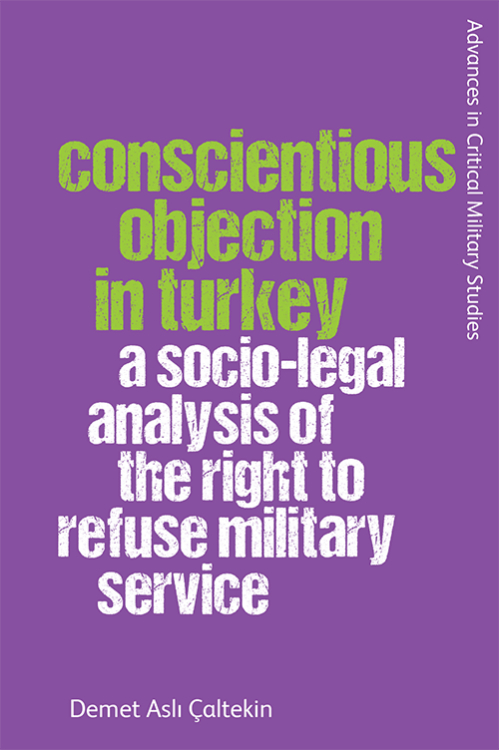

by Demet Aslı Çaltekin

Can you tell us a bit about Conscientious Objection in Turkey: A Socio-legal Analysis of the Right to Refuse Military Service?

My book is about the interplay between the socio-cultural norms and non-recognition of the right to conscientious objection in Turkey, a country that adopts a male-conscription system with no alternative service. Drawing on semi-structured interviews with conscientious objectors, it provides an empirical and a socio-legal analysis of the right to conscientious objection in Turkey by asking: how do international and domestic laws approach the conflict between the law and conscience? Why does Turkey insist on the non-recognition of the right to conscientious objection? How are those pursuing their conscience affected by such non-recognition? These questions are important as the law is not only shaped by the socio-cultural structures in which it operates but also (re)shapes these structures by bringing new perspectives into the matter and by framing people’s perceptions of the world. Therefore, any attempt to create a social change also necessitates understanding and challenging the legal framework. In this light, my book argues that one cannot fully understand and, as a result, resist the militarisation of society without understanding the relationship between the law and social norms.

What inspired you to research this area?

My book dates back to my childhood. When I was in primary school in Turkey, every morning, I stood up with all the other students and recited the national pledge of allegiance:

‘I offer my existence to the Turkish nation as a gift’.

Hardly surprising that outside school, as a kid, I felt the urge to behave like a soldier whenever I encountered one, giving them a military salute. Till the end of my high school, on Friday ceremonies, right before leaving the school, I read the national anthem of Turkey and burst out:

‘Smile upon my heroic nation! Why the anger, why the rage? Our blood which we shed for you shall not be worthy otherwise’.

These seemingly trivial practices (signs of normalisation of militarism) encouraged me to question the normalisation of the military’s presence in our daily lives.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

Conducting fieldwork in Turkey and interviewing conscientious objectors was the most exciting part of this book. This allowed me to provide empirical insights into how conscientious objectors experience the (non)recognition of the right to conscientious objection. I believe that one cannot simply examine the legal texts on paper but must instead investigate empirically how such laws operate within society, looking particularly into questions, such as: how does the current legal framework affect the lives of conscientious objectors? Without an empirical focus, anti-militarist researchers risk detaching themselves from the real world.

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

It was Ramadan when I conducted my fieldwork. I went to Taksim Square in Istanbul to interview a religious (male) conscientious objector. On my way there, I finished a bottle of water assuming that he would be fasting and that it would be inappropriate to drink water before someone fasting.

I was unaware of my bias.

As when I got there, the scene that I had pictured in my mind was completely different to what I found. I came across him in a shabby music room smoking and having a beer. From the first moment of the interview, I understood that his religious identity [here I am referring to Islam] differed from my understanding of what it means to be a Muslim. His perspective showed me that a wide range of motivations and beliefs could lead individuals to declare their conscientious objections. While he made me aware of my bias, my other participants, showed me how the law is a vital tool in the struggle of a social movement aiming to bring about a social change. They revealed once again the necessity to carry the struggle into the legal arena. In the face of my participants’ endless energy, hope, and constructive criticism, I finished my fieldwork regaining my faith in the idea that ‘a change is possible’.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

Conscientious objectors’ desire to bring about a change in society inevitably leads them to challenge the gendered roots of militarism. Women are challenging these roots by declaring their conscientious objection to the compulsory military service. Women’s demilitarisation attempts in Turkey (where women are not conscripted, but they declare their conscientious objection to compulsory military service) broadens the discussion on the right to conscientious objection–an objection that may initially be perceived as only a demand for an exemption from compulsory military service.

Interested in all things Politics? Why not sign-up to our mailing list?

Dr Demet Asli Caltekin, with Durham University, Law School, will be hosting a hybrid book launch in April. You can contact her demet.a.caltekin@durham.ac.uk for more details.

About the author

Dr Demet Asli Caltekin is an Assistant Professor in Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at Durham University, Law School. Her research investigates theoretical, sociological, and empirical aspects of law by employing feminist and socio-legal methods. Dr Caltekin holds a PhD in Law from Durham University and LLM in Human Rights and Humanitarian Law from University of Essex, School.

About the book

Order your copy – Save 30% with discount code NEW30

Conscientious Objection in Turkey: A Socio-legal Analysis of the Right to Refuse Military Service

by Demet Aslı Çaltekin

Provides a socio-legal analysis of cultural norms and the right to conscientious objection in Turkey