by Paul Malgrati

Every year, on 25 January, Burns Night offers a remarkable opportunity for Scottish political parties to issue a statement about the Scottish nation, its identity, and its situation. Last year, in 2022, Scotland’s First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, released a video celebrating Burns as a poet of ‘empathy and solidarity’, befitting in the post-pandemic context, after two years of collective carefulness. Three years earlier, before international travels were banned by successive lockdowns, it was Sturgeon’s Europe Minister, Ben McPherson, who tweeted photographs from a Burns Supper in Paris, where the Scottish Government had recently opened a diplomatic hub. This pro-European statement could be read as a response to the Burns Supper organised at No.10 in 2018 by Prime Minister, Theresa May, who aimed to celebrate Scotland’s ‘greatly valued contribution’ to ‘our enduring Union’.

Such uses of Scotland’s national poet beg questions: firstly, why do British politicians, often focused on economic, technocratic matters, feel the need to requisition the memory of a poet who died 227 years ago? In other words, why does Burns’s legacy count for so much that it could ever become a matter of state? And secondly, has the politics of Burns’s memory changed over the years?

My monograph, Robert Burns and Scottish Cultural Politics. The Bard of Contention (1914-2014), forthcoming in March 2023 with Edinburgh University Press, aims to answer these questions.

Considering Burns’s political afterlife since the time of his death —with a particular focus on the last hundred years— it demonstrates how the poet’s central place in Scottish cultural memory has turned into an unavoidable site for Scotland’s democracy. Indeed, Burns has been hailed as ‘Scotland’s national bard’ since at least 1859 —the year of his Centenary— when mass celebrations of the poet swept both Scotland and the Scottish diaspora. As such, Burns’s memory became the unofficial representative of a stateless nation, voicing the soul of Scotland and its many accents.

Nevertheless, although the poet has become commonplace, his message remains ambiguous. Oscillating between patriotic dirges, egalitarian lines, Scots songs, English eloquence, and royalist odes, Burns’s work lends itself to interpretations from across the political divide. In other words, the annual celebration of Burns’s birthday has become an occasion for the nation, as a political entity, to ponder different definitions of itself through contradictory readings of its legendary poet. All modern political movements have tried to co-opt Burns in an attempt to sway Scottish public opinion: from Tories and Liberals to Labour politicians, Communists, nationalists, fascists, anti-racists, feminists, and green activists.

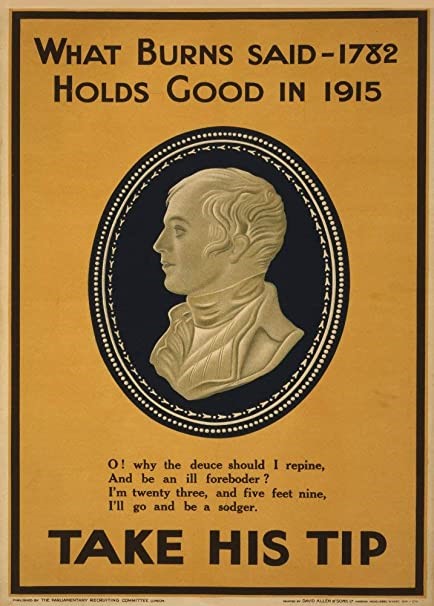

Yet beyond the list of Burns’s potential (mis)readings, my book further aims to outline an arc in the eternal return of annual Burns commemorations. Indeed, a close attention to chronology reveals a more subtle ideological shift in the poet’s memorialisation since the time of his death. To put it briefly, the dominant reading of Burns in the nineteenth century turned his poetic ambiguities into a paragon for Scottish unionist sentiment, conflating Scottish vernacular pride with the project of Britain’s multi-ethnic Empire. Such a view of Burns became exacerbated, particularly during the First World War, as army recruiters, Kirk ministers, mainstream newspapers, and Burns Clubs requisitioned the poet’s martial imagery, from ‘Scots wha hae wi’ Wallace bled’ to ‘Does Haughty Gaul’s Invasion Threat?’, for King and Country.

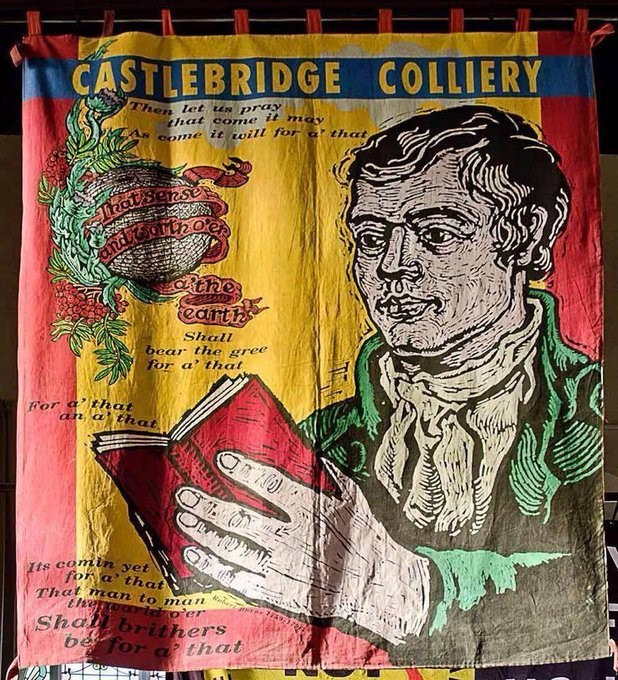

By contrast, Burns’s reception in the last five decades has become increasingly tied with the debate on Scotland’s constitution. Whilst in the nineteenth-century Burns’s personal contradictions fueled Scottish commitment to a pluralistic Empire, in the late twentieth century they served a critique of British constitutional imbalance, thus paving the way for Scottish Home Rule. Such association between Burns’s legacy and Scottish Devolution became salient, in July 1999, at the inauguration of the new Scottish Parliament, when the singer Sheena Wellington performed Burns’s egalitarian anthem, ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ that’, to celebrate Scotland’s partially recovered sovereignty.

So how did Burns’s reception change from a predominantly imperial, unionist reading to an increasingly constitutional, nationalist interpretation? My book identifies at least three factors behind this shift: (1) the end of Empire, which altered Burns’s image as a civilising Scot and prompted new readings of his songs as the repository of Scotland’s indigenous folk (2) Thatcherism, which divided Scottish and English cultural politics and undermined Labour’s post-war vision of Burns as an egalitarian symbol of Welfare Britain (3) the role of contemporary Scottish writers who, since the 1980s, have revived Burns-like, bardic postures, conflating Scottish vernacular literature with demands for Scottish self-rule.

Such tendencies were only emphasised in the run-up to the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence as the SNP’s First Minister, Alex Salmond, and the broader Yes Campaign, blended Burns’s egalitarian message with hopes of Scottish autonomy. Certainly, this does not mean the poet’s legacy has become the preserve of Scottish nationalists. Indeed, uses of his memory also persist in Tory, unionist circles, as demonstrated by Theresa May’s Burns Supper in 2018. What is sure, however, is that from the SNP to the Tories, few voices in contemporary Scottish politics seem capable (or willing) of opposing the narrative which conflates Burns’s legacy with the past, present, and future of Scotland’s constitution. In other words, whilst the poet’s memory has served as a major symbol of Scottishness since the nineteenth century, it was not until the last four decades, that his image developed into a more distinct symbol of national self-rule —an icon used not only to define the identity of a stateless nation but, more markedly, to advocate or oppose the creation of a Scottish nation-state.

About the book

Robert Burns and Scottish Cultural Politics is now available to pre-order.

Until the end of January 2023, use the code ‘BURNS30’ for 30% off.

About the author

Paul Malgrati was born in France and moved to Scotland in 2013, earning his award-winning PhD in Scottish History and English at the University of St Andrews in 2020. From 2020 to 2022 he was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Glasgow’s Centre for Robert Burns Studies. He currently lives in Switzerland, working as a teacher and researching Scottish literature as an independent scholar. He is the author of a number of articles on both Robert Burns and on twentieth-century Scottish poetry. His first book of poems, Poèmes Écossais (2022) was shortlisted for the Edwin Morgan Poetry Prize. It is believed to be the first book of Scots poetry by a non-native Anglophone. Robert Burns and Scottish Cultural Politics is his first monograph.