Steve Newman, Temple University

Q: What Scottish play, published in 1725, reached over 100 printings by 1800, was called ‘the noblest pastoral’ by Robert Burns, inspired more than forty paintings, more than ‘from the entire works of Chaucer, Defoe, Swift, Richardson, or Fielding’ (R. Altick, Paintings from Books), and was performed by amateur companies throughout Scotland as late as the end of the 19th century?

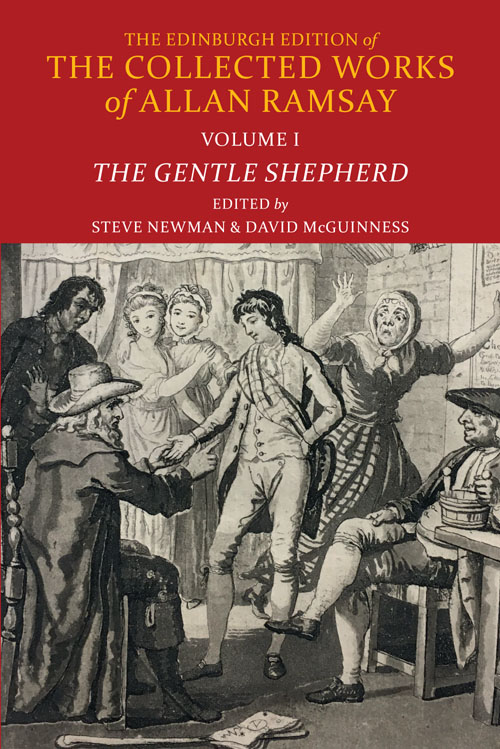

A: Allan Ramsay’s The Gentle Shepherd, the first dependable scholarly edition of which has just been published by EUP as the first volume of The Collected Works of Allan Ramsay.

Ramsay’s Rising Reputation

When I began in Scottish studies some 25 years ago, Ramsay was certainly known as a significant figure in what is often referred to as the Scots Vernacular Revival. But he was all-too-often dismissed as the less-talented precursor to Robert Fergusson and Burns, an arriviste who mangled traditional Scottish music and texts in his pursuit of polite audiences.

Thanks to the labors of scholars like Murray Pittock, the general editor of The Collected Works, he is now getting his due as one of the founding figures in the reinvigoration of Scots as a literary language and in the Scottish Enlightenment, a cultural broker extraordinaire who also founded the first Scottish theatre and academy of the fine arts.

The Story of The Gentle Shepherd in Its Historical Moment

The Gentle Shepherd, his best-known text, helps to show why he merits that reputation.

The story is simple enough: The beloved and exiled laird, Sir William Worthy, returns to reclaim his estate in the Pentland Hills after the Stuarts win the War of the Three Kingdoms. Disguised as a ‘spae-man,’ or fortune-teller, he has a fit of ‘the second sight’ revealing that Patie the shepherd will soon have his status raised. He then removes his disguise to confirm his own prophecy.

While this would seem to be a fortunate turn of events for Patie, it risks sundering him from his love, a shepherdess named Peggy.

But things turn out well!

Peggy is revealed to be a gentle shepherdess—Sir William’s niece, in fact—and in this era being first cousins was no bar to marriage! So she and Patie are betrothed, and so are their rustic friends, the bashful but faithful Roger and the strong-willed Jenny.

Meanwhile, in the ‘low’ subplot, the clownish Bauldy is foiled in his appeal to Mause to use her powers as a witch to turn Peggy’s affections to him. In fact, Mause is the well-educated servant who spirited Peggy away when she realized her aunt and uncle were conspiring against her life. Mause and the sharp-tongued Madge, Peggy’s adopted aunt, revenge themselves on Bauldy by giving him a terrible fright by dressing up as ghost and witch. His attempt to have them prosecuted comes to naught thanks to Sir William’s more enlightened views. Bauldy repents, and the play ends with Peggy singing Ramsay’s adaptation of the traditional song, ‘Corn Rigs,’ envisioning a new day for the happily married couple in a restored pastoral landscape.

This summary gives some sense of how cannily Ramsay blends a celebration of traditional Scottish life and language with a forward-looking vision of ‘improvement,’ to use the Enlightenment keyword. Returning to a moment before the controversial Union of 1707, Ramsay imagines a Scottish community where ‘second sight’ is a game and witchcraft mere superstition. In their place are love marriages which also make economic sense and increasing literacy; Patie is revealed to be a great reader and Roger swears he will start reading, too. As for Sir William, unlike the cruel landlords whose enclosures lead the Galloway Levellers to take up arms just as Ramsay is composing his play, his tenants report that he is a kind landlord, happy for them to keep the profits of their labors.

The Reception of The Gentle Shepherd

The play’s complex relationship to its historical moment captures only a fraction of its interest and importance.

The editor of the music for this edition, David McGuinness, discusses that crucial element of the play in a separate blog post that you can read here.

Also worth considering is the rich history of its performance and reception. For instance, while The Chartist Circular of February 1841complains that teaching The Gentle Shepherd in schools—a complaint that suggests the play’s reach—cozens students into subordination, it nonetheless became a cherished part e of Scottish popular culture. In the online database of nearly 700 Gentle Shepherd performances that will be appearing on the website for The Collected Works in July, we can find not only professional performances in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen, London, New York, Philadelphia, Charleston (South Carolina), Melbourne (Australia) and other places but, as mentioned above, scores of amateur performances, many of them for charitable purposes, such as a performance at the Assembly Room at Annan on 30 May 1817 for ‘the industrious labouring classes in necessity’ or 12 February 1857 to benefit the Ayr Fever Hospital or 12 April 1858 by the Kirkmahoe Amateur Theatrical Club to benefit the Dumfries Brass Band.

The Aims of Our Edition

It is our hope that this edition, the first to be properly collated against all manuscripts and relevant printings and the first with significant attention to the music, will help new generations of scholars, students, and performers find their way into and through this influential play.

I feel privileged to have edited the text and am grateful to have had the chance to work with David and our Research Associates, Craig Lamont and Brianna Robertson-Kirkland as well as the rest of the Ramsay Team, Murray Pittock, Rhona Brown, and James Caudle. I’m also grateful to EUP for publishing The Collected Works and the Arts and Humanities Research Council for a major grant for this and the forthcoming volumes.

Please enjoy The Gentle Shepherd, and let me know what you think at snewman@temple.edu!

About the author

Steve Newman is an associate professor of English at Temple University, specialising in British Literature of the Long Eighteenth Century and Scottish Literature.

You can find out more about The Gentle Shepherd on our website. Interested in buying it? Use discount code EVENT30 at checkout to save 30%.

Want to hear more about whats publishing in Literary Studies at Edinburgh University Press? Sign up to our mailing list! You’ll be the first to hear about new books, blog posts and events.