by Alice Maurice

It has been a long time since Will Smith slapped Chris Rock at the Oscars. It’s been two whole months – by today’s standards, an eternity. Even after a week, it had been thoroughly washed and rinsed in the news cycle. Comedian Jerrod Carmichael, hosting SNL only six days later, vowed that he was more than over it. He opened his monologue with a defiant declaration: “I’m not gonna talk about it.” He was all talked out, he said, and he seemed to speak for us all when he noted that, even on day six, it already felt like it had happened a long time ago: “It feels like we’ve been living in the wake of it our entire lives.” In a way, we have.

For me, this very twenty-first century media event —a real act of violence, watched live by millions and almost instantly immortalized in jokes and memes — takes its place as part of the tangled history of the face on screen.

In particular, the incident made me think of slaps (and all sorts of other violence done to the face) in the history of both comedy and drama in cinema. Slapping and generally mistreating the face has been a staple of slapstick comedy since the beginning: its iconic gag is, after all, the “pie in the face” (perfected and raised to perhaps its highest form in the teens by the Keystone Film Company). But not everyone found it funny: it is said that American media mogul William Randolph Hearst became incensed on the set of a King Vidor movie when he found out that his wife, Marion Davies — who had made the successful transition from dramatic actress to comedienne in the 1920s — was slated to be on the receiving end of a pie in the face. According to Vidor, Hearst wouldn’t allow it, no matter how much he pleaded. Apparently this was seen as too insulting, too unbecoming, too violent – just too much. In the end, they decided to spray seltzer in her face instead. Perhaps when it came to Hollywood, Hearst knew that even for a comedienne, a pretty face was serious business – or as they were fond of saying back then: “Her face was her fortune.”

Such facial antics were reserved for comedies, while the closeup of the face in film dramas became the crucial, definitive shot of the cinema, establishing character psychology and motivation, as well as iconic, glamourous stardom. Again, serious business. And yet the serious, sacred nature of the face is precisely what gives the slap (or the custard pie) its power.

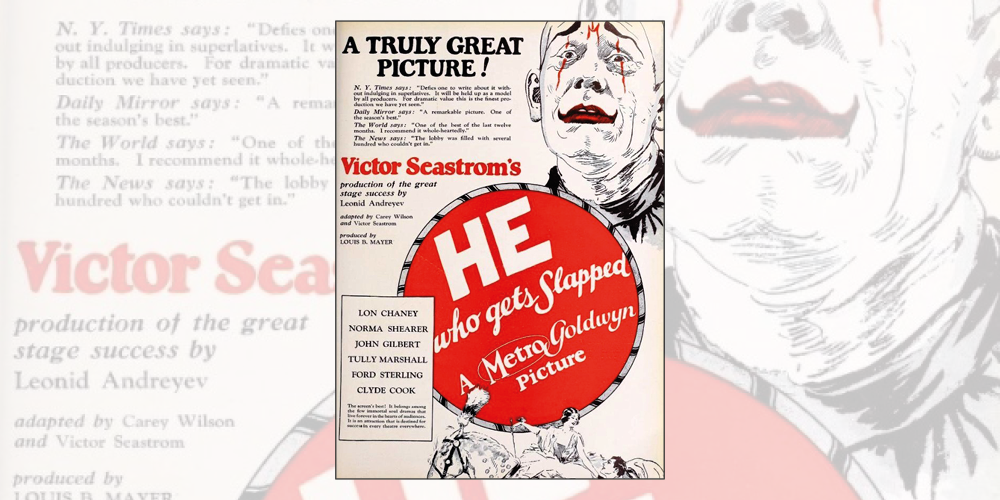

But the slap was also played for pathos. The meaning of the slap is perhaps most poignantly and cruelly explored in the 1924 silent film He Who Gets Slapped (Victor Sjöström), one of the most successful films of its day. It featured Lon Chaney (the “man of a thousand faces”), who spends much of the film in clown makeup performing his signature act: being slapped repeatedly by the other circus performers while the audience roars with laughter. It’s a masochistic tour-de-force, born from emotional pain. Early on in the film, Chaney’s character, a scientist, is betrayed by his wife and humiliated in front of his peers, as his patron (his wife’s lover) takes credit for his work and dismisses him with a slap. And so he goes behind the clown’s mask, replaying his humiliation over and over again. In the film, the slap functions as the ultimate sign of emasculation.

The need to don a mask makes sense when the face is attacked. A slap is a gesture: to slap the face is a sign of disrespect, of silencing and dismissal – a kind of erasure. It erases the face (or the expression on the face) and the personality behind it. That seemed to be Smith’s objective: to wipe the smile off Rock’s face, to slap the joke out of his mouth. It did seem to silence him, at first. We didn’t hear much from the man who got slapped (though we heard plenty from the slapper). At his first post-Oscars stand-up gig, he didn’t talk about it; instead, he said he was “still processing it.” A month later, he got his chance. After a man tried to attack Dave Chappelle during a comedy show in Los Angeles, Rock, who was also there, quipped, “Was that Will Smith?” Comedy is all about timing.

The fact that this was all about comedy suggests the intimate relation between laughter and tears, comedy and pain. In the history of cinema, attacks on the face have straddled the boundary between comedy/grotesquerie and drama/pathos. As theorists from Georg Simmel to Gilles Deleuze have told us, the face – as the site of expression and identity and the locus of speech – has the power to signify like nothing else. A slap in the face (the phrase itself a synonym for insult) still has the power to jolt us, to make us recoil, even if we are just spectators to the act.

About the Book

This book will consider the screen face from a variety of perspectives, across time periods and media, bringing together essays on topics ranging from early cinema to contemporary digital media – from photogénie to facial recognition, celebrity culture to digital creatures. It explores how screen culture builds on and complicates our urge to search the face for answers to our most intractable questions.

About the Author

Dr Alice Maurice is an Associate Professor of English and Cinema Studies at University of Toronto.

Sign up for our mailing list!

Interested in learning more about this book and other titles from Edinburgh University Press? You can sign up for our mailing list here!

You can also read more of our film studies blogs here.

There was something similar in The Blue Angel (1933), starring Marlene Dietrich.